Return to

Return toAviation Answer-Man

Gateway

Return to

Return to

Aviation Answer-Man

Gateway

Return to

Return to.

Chapter 2

The

Bleriot Model XI

Copyright 2000, 2001, 2002 by Richard Harris

All Rights Reserved

All-too-often overlooked by American aviation writers, the Bleriot Model XI set the standard for early airplanes.

All-too-often overlooked by American aviation writers, the Bleriot Model XI set the standard for early airplanes.

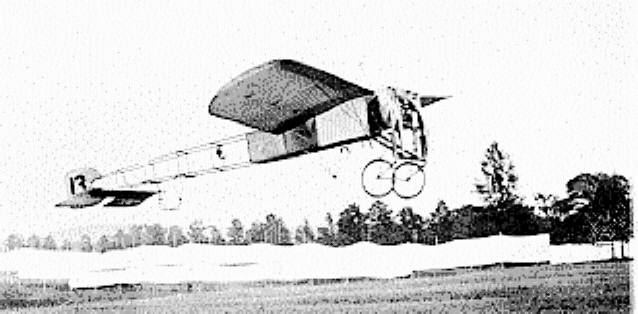

The Wright Brothers' quirky biplane flyer (a canard biplane, with wing-warping, skid landing gear, twin pusher propellors chain-driven by a shared single engine, and people sitting in the open on the wing) is often painted as the essential "first" airplane (1903). But it can be seriously argued that the Wright brothers design was utterly impractical , even in its later models (such as the classic Wright Model B, shown below, left).

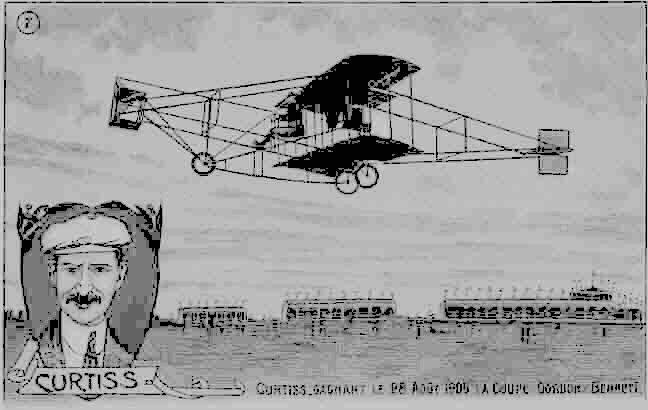

To understand the significance of the Bleriot XI monoplane, one must keep in mind what a bizarre and amazing variety of aeroplanes first took to the skies. From the Langley Aerodrome, to the Wright Flyer to the Farman Biplane to Santos-Dumont's "box kite" plane, to the Curtiss Pusher -- no one could quite find a clean, basic, reliable, maneuverable, truly practical airplane. They could fly, but not well, not cheaply, and not quickly. And above all, not reliably. And, by today's standards, many of these aircraft looked more like flying puzzles than airplanes; and to their pilots, many handled like puzzles as well.

To understand the significance of the Bleriot XI monoplane, one must keep in mind what a bizarre and amazing variety of aeroplanes first took to the skies. From the Langley Aerodrome, to the Wright Flyer to the Farman Biplane to Santos-Dumont's "box kite" plane, to the Curtiss Pusher -- no one could quite find a clean, basic, reliable, maneuverable, truly practical airplane. They could fly, but not well, not cheaply, and not quickly. And above all, not reliably. And, by today's standards, many of these aircraft looked more like flying puzzles than airplanes; and to their pilots, many handled like puzzles as well.

Most aeroplane designers clung stubbornly (perhaps vainly) to their original design concepts -- only tweaking them slightly to try and make things work. But one ambitious and energetic aviator kept daringly (some would say "frantically") trying every design idea in sight, in rapid succession. The result would change airplanes forever. The Wright design, and virtually all others, were soon eclipsed by the first truly practical airplane ever mass-produced: the Bleriot Model XI (1908). The Bleriot design would clearly establish the basic design shape of 20th-Century airplanes.

Most aeroplane designers clung stubbornly (perhaps vainly) to their original design concepts -- only tweaking them slightly to try and make things work. But one ambitious and energetic aviator kept daringly (some would say "frantically") trying every design idea in sight, in rapid succession. The result would change airplanes forever. The Wright design, and virtually all others, were soon eclipsed by the first truly practical airplane ever mass-produced: the Bleriot Model XI (1908). The Bleriot design would clearly establish the basic design shape of 20th-Century airplanes.

Frenchman Louis Bleriot (pronounced "LOO-ee BLAIR-ee-O") built a monoplane -- not a biplane -- with a conventional tail, wheels and tailskid, and a front-mounted engine, turning a single front-mounted "tractor" propellor (pulling the airplane, rather than pushing), bolted directly to a short shaft coming out of the engine (a concept known later as "direct drive").

Frenchman Louis Bleriot (pronounced "LOO-ee BLAIR-ee-O") built a monoplane -- not a biplane -- with a conventional tail, wheels and tailskid, and a front-mounted engine, turning a single front-mounted "tractor" propellor (pulling the airplane, rather than pushing), bolted directly to a short shaft coming out of the engine (a concept known later as "direct drive").

The Model XI monoplane (below, left) had another advantage: low weight. While other aviators had tried to build massive planes around powerful engines, Bleriot settled for about half the prevailing power, in his 25-hp Anzani engine (an expensive but efficient, lightweight engine), and was then able to build a plane with about half the airplane design weight of many leading designs. Small wonder, then, that Bleriot was able to get by with one set of wings, when nearly all other early aeroplanes had two.

While Bleriot copied the Wright's wing-warping idea for roll-control, Bleriot also experimented with more modern ailerons (now used almost universally today). In fact, the Bleriot XI was the product of countless experiments by the intrepid Bleriot -- including dozens of crashes. The Wright brothers had introduced to aircraft development the orderly scientific method of laboratory experimentation and testing. But Bleriot became the epitome of the daredevil-maniac inventor, relentlessly flight-testing his designs by simply flying them until they crashed. In the process, he not only broke several bones, but himself -- financially -- whittling away both his own small fortune and his wife's.

In 1909, six years after the Wright brothers' famous first controlled, powered flight, the "aeroplane" was still a fairly useless invention. Planes still mostly flew about in circles, or on very short cross-country hops. Most did little more than put on flying exhibitions for the public.

In 1909, six years after the Wright brothers' famous first controlled, powered flight, the "aeroplane" was still a fairly useless invention. Planes still mostly flew about in circles, or on very short cross-country hops. Most did little more than put on flying exhibitions for the public.

But the excitement and fascination with flying machines had caught the attention of the world, and the daredevils who flew them were being rewarded with fame and fortune with each spectacular new achievement, like Eric Sommer (above, left) who wowed the world in his Farman Biplane, in early 1909, with a record-setting "long-distance" flight of 37 miles -- over mostly open land, in good weather.

But no one had successfully flown across the open sea. In a day when airplanes and their engines were such finicky, unreliable contraptions, and exceptionally vulnerable to the elements, the idea of setting out over open sea in an aeroplane was generally regarded as sheer madness.

But no one had successfully flown across the open sea. In a day when airplanes and their engines were such finicky, unreliable contraptions, and exceptionally vulnerable to the elements, the idea of setting out over open sea in an aeroplane was generally regarded as sheer madness.

Yet, where there was an obstacle, there was money to be made flying over it. The London Daily Mail newspaper, eager for exciting news to boost its sales, offered a big cash prize for the first person to fly across the narrow English Channel -- the 20-mile-wide stretch of open sea separating Britain from and France and the rest of Europe.

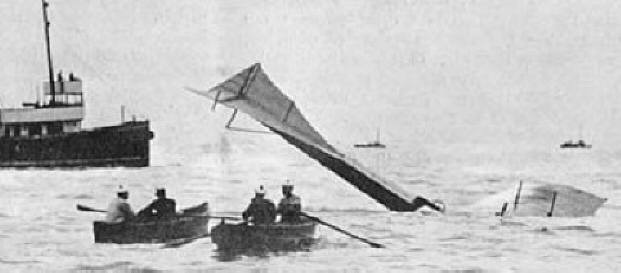

Several eager aviators quickly gathered for the attempt, but disaster befell each -- as weather, engine trouble, and other hazards thwarted their attempts. The lucky ones just got wet (like Hubert Latham, at right, above, being rescued from the remains of his Antoinette aeroplane, floating in the English Channel).

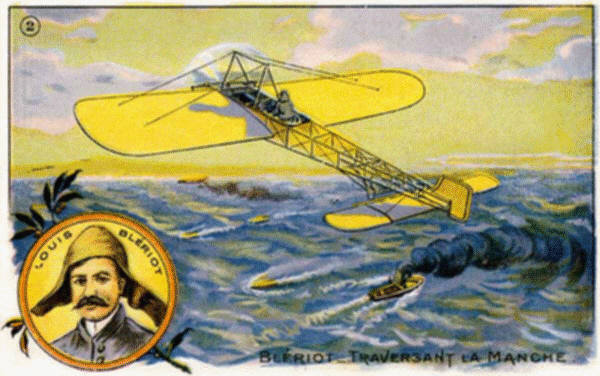

But Louis Bleriot was determined to try. In the pre-dawn calm of July 25, 1909, with a leg still injured from a previous flight, Louis Bleriot strapped his crutches to the side of his tiny Model XI monoplane, and took off from the French coast, on what would become the most important 37-minute flight in history.

But Louis Bleriot was determined to try. In the pre-dawn calm of July 25, 1909, with a leg still injured from a previous flight, Louis Bleriot strapped his crutches to the side of his tiny Model XI monoplane, and took off from the French coast, on what would become the most important 37-minute flight in history.

He was soon tackling nasty winds (which would halt a competitor who took off just behind him). The winds blew him off course, and he began to wonder if he would reach the English shore before battling the wind consumed all his fuel. He finally caught sight of the English coast, and was then greeted by the early aviator's greatest enemy: converging clouds.

Once enveloped in the blinding clouds -- slung about by the forces of gravity, the centrifugal force in turns, and the acceleration/deceleration of the plane as it maneuvers -- most early aviators would quickly become completely disoriented, losing all sense of direction, or of even which way was up. (Even today, the typical pilot -- if he has no working instruments to guide him -- quickly becomes disoriented in a cloud, and loses control of the plane within a couple of minutes.)

Once enveloped in the blinding clouds -- slung about by the forces of gravity, the centrifugal force in turns, and the acceleration/deceleration of the plane as it maneuvers -- most early aviators would quickly become completely disoriented, losing all sense of direction, or of even which way was up. (Even today, the typical pilot -- if he has no working instruments to guide him -- quickly becomes disoriented in a cloud, and loses control of the plane within a couple of minutes.)

Desperately struggling through the clouds, with not even a compass, Bleriot kept on -- pulled through the air by his trusty little Anzani engine. He finally spotted a clearing in the clouds that showed the English coast -- revealing that he was blown far off course.

Fighting winds that tried to blow him back out to sea, Bleriot -- seeing a Frenchman waving a flag in an open field -- crash-landed there in desperation. The Frenchman had expected Bleriot's competitor, who'd been caught by winds and forced back. But Bleriot had made it, alone and alive (below, man at left in front of plane).

Bleriot won the prize for first airplane pilot to "successfully" cross the English Channel -- creating a storm of world attention by both crossing a sea and flying over the borders between two countries. In the eyes of the world, the airplane suddenly changed from a flying toy into a credible tranportation concept and a potential military weapon.

Bleriot won the prize for first airplane pilot to "successfully" cross the English Channel -- creating a storm of world attention by both crossing a sea and flying over the borders between two countries. In the eyes of the world, the airplane suddenly changed from a flying toy into a credible tranportation concept and a potential military weapon.

Though it would take a year for anyone else to succeed at the aerial crossing, people around the world were thunderstruck by the implications. The natural barrier of ocean was no more. What could take an hour by fast ship had happened in half the time. Flying above the aim of defensive cannon, crusing high over waves and rocks and cliffs and fences and walls, the aeroplane suddenly seemed immune to the normal powers of national security.

The airplane was finally taken seriously by a substantial percentage of the world's movers and shakers. Bleriot's flight across the open sea was the single most important flight in the history of aviation (with only the slight possible exception of the Wrights' first flight, or Lindbergh's later solo crossing of the Atlantic). Bleriot suddenly became the world's most respected aviator (in car at right, tipping his hat to the crowd).

The airplane was finally taken seriously by a substantial percentage of the world's movers and shakers. Bleriot's flight across the open sea was the single most important flight in the history of aviation (with only the slight possible exception of the Wrights' first flight, or Lindbergh's later solo crossing of the Atlantic). Bleriot suddenly became the world's most respected aviator (in car at right, tipping his hat to the crowd).

Immediately after the Channel crossing, the Bleriot XI quickly became known as the standard of quality and practicality for airplanes. Bleriot was swamped with orders, and the Bleriot XI monoplane became the world's first truly mass-produced aircraft, and, in the process, started the mass-production of airplanes, and launched the French aircraft-manufacturing industry. Over the next several years, nearly a thousand Bleriot monoplanes were built by various parties.

Its performance was initially typical for the times, at around 40 miles per hour. But later models, with the popular, larger Gnome rotary engine, could zip along admirably at over 60 miles per hour. By the end of the following year (1910) a Bleriot monoplane would hold the world speed record, at over 68 miles per hour. And the world altitude record, at 10,476 feet (almost too high to breathe, in the thin air), would also be set by a Bleriot pilot.

Its performance was initially typical for the times, at around 40 miles per hour. But later models, with the popular, larger Gnome rotary engine, could zip along admirably at over 60 miles per hour. By the end of the following year (1910) a Bleriot monoplane would hold the world speed record, at over 68 miles per hour. And the world altitude record, at 10,476 feet (almost too high to breathe, in the thin air), would also be set by a Bleriot pilot.

For the next several years, every major air meet and air race in Europe included a Bleriot among its winners, and the Bleriot was used to set countless records and aviation firsts. A Bleriot was the first to cross a mountain range (the Swiss Alps), the first airplane from which a planned parachute jump occured, and it became the first military airplane in Europe (above, left).

It was nearly as prominent in the United States, where it introduced a whole new level of value to flying. A Bleriot XI initiated the first American airmail service (Nassau, NY to Long Island, NY, 1911). Many early American aviators bought Bleriots or built their own copies -- either from kits, or from plans and pictures.

It was nearly as prominent in the United States, where it introduced a whole new level of value to flying. A Bleriot XI initiated the first American airmail service (Nassau, NY to Long Island, NY, 1911). Many early American aviators bought Bleriots or built their own copies -- either from kits, or from plans and pictures.

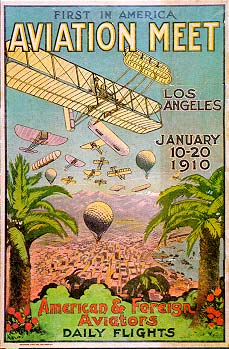

Bleriot Monoplanes were the star of many early American airshows, and probably the most coveted and imitated airplane in the beginning years of powered flight. The poster (at left) for the first American air meet, with proper national pride, features the Wright Flyer in the foreground -- but the background is chiefly cluttered with the various Bleriots which actually dominated the show.

A copy of the Bleriot was assembled by an Oklahoma farmer named Clyde Cessna, and became the first "Cessna" aircraft -- leading indirectly to the creation of Cessna Aircraft Company, the world's leading builder of light planes. Cessna first flew in his 1911 "Silverwings" Bleriot copy (shown at right), touring air shows in America's heartland -- including in Wichita, Kansas, where he would later socialize at the nation's first commerical airplane company, Swallow Aircraft... and then help Swallow employees Walter Beech and Lloyd Stearman to start its famous rival, Travel Air. Cessna would then leave the latter company in a dispute with its general manager, Walter Beech, over which was better: biplanes or monoplanes. Cessna, who had learned to fly in his "Queens monoplane" -- a copy of the Bleriot monoplane -- struck off on his own to build monoplanes, and the rest is history.

A copy of the Bleriot was assembled by an Oklahoma farmer named Clyde Cessna, and became the first "Cessna" aircraft -- leading indirectly to the creation of Cessna Aircraft Company, the world's leading builder of light planes. Cessna first flew in his 1911 "Silverwings" Bleriot copy (shown at right), touring air shows in America's heartland -- including in Wichita, Kansas, where he would later socialize at the nation's first commerical airplane company, Swallow Aircraft... and then help Swallow employees Walter Beech and Lloyd Stearman to start its famous rival, Travel Air. Cessna would then leave the latter company in a dispute with its general manager, Walter Beech, over which was better: biplanes or monoplanes. Cessna, who had learned to fly in his "Queens monoplane" -- a copy of the Bleriot monoplane -- struck off on his own to build monoplanes, and the rest is history.

In a more important way, the Bleriot put clearly to rest -- for over half a century -- the question of where to put the elevators and rudder, and the propellor and engine, and what landing gear configuration to use. The canard-first, pusher-prop, skid-based Wright design quickly faded into oblivion, and in time even the concept of the biplane would be overcome by the Bleriot-style monoplane.

More subtly, perhaps, the Bleriot established a more fundamental design standard: a single, long, slim streamlined fuselage, starting from the engine to (mostly) enclose the pilot, and taper neatly into the tail boom -- a concept we take for granted today, but which was hardly a given in its day. To control the plane, Bleriot incorporated one of the first "joystick-and-foot-pedal" control systems, later to be rearranged slightly and then become standard throughout the world (still in use in virtually all jet fighters, today).

While Bleriot may not have been first to fly any of these design concepts, it was arguably his Model XI which made them all credible and (except for the single-wing design) readily accepted throughout the world.

In short, the widespread competition to be "the first to fly" (a controllable airplane) ensured that some successful flying machine -- by the Wright brothers or others -- was inevitable. But it was the Bleriot XI that was the first airplane to become practical and popular, and it was the Bleriot that set the basic design of airplanes for most of the 20th-Century.

Why this plane stands out from its "peers."

While many other planes have been important, few (if any) others had nearly so pivotal an impact on aviation or on history. The Bleriot XI is one of the "indispensible" aircraft -- aircraft with no significant concievable substitute available at their juncture in history.

Looking at the myriad assortment of early airplane designs, and comparing them to today's planes, the Bleriot stands out as the one which is most completely typical of the modern airplane. The gliders of Otto Lillienthal (left) and Octave Chanute, the Wright Flyer, the Curtiss Pusher, and others, brought significant innovations. But they had serious shortcomings, too.

Looking at the myriad assortment of early airplane designs, and comparing them to today's planes, the Bleriot stands out as the one which is most completely typical of the modern airplane. The gliders of Otto Lillienthal (left) and Octave Chanute, the Wright Flyer, the Curtiss Pusher, and others, brought significant innovations. But they had serious shortcomings, too.

A quick look at some of the prominent planes in Bleriot's time sheds glaring light on the value that the extraordinary/ordinary Bleriot airplane brought to aviation. Four are shown below, with their strong points ("right") and weak points ("wrong") noted. Note the differences between these planes and Bleriot's Model XI, and you'll quickly see that Bleriot's design proved decidedly more enduring and practical -- and set the standard for future airplanes -- while these other famous, pioneering designs soon faded into oblivion.

Langley Aerodrome right: puller-propellor (on 1914 model); vertical stabilizer & stabilizer/elevator on tail; diehedral (wing up-sweep) for stability; efficient, powerful, gasoline radial engine. wrong: no roll control; rudder uselessly placed in middle of airplane; tandem wings (one in front of the other); large, flimsy structure; sail-like pusher propellors on either side of pilot, in the original design, dangerously close to the pilot's head; bulky engine, too far from propellors; too big; needed catapult to take off; no fuselage. Slow (25mph). Disintegrated on takeoff twice, finally flying briefly (in heavily modified Curtiss version), in 1914. |

Santos-Dumont's Model 14bis right: very light weight; gasoline engine; wheels for landing gear; and it actually flew (barely). wrong: just about everything else. |

Wright Flyer (Model A shown here) right: added roll-control to pitch and yaw control -- yielding first fully-controllable airplane; powered by a lightweight, efficient gasoline engine. wrong: roll-control by wing-warping; no fuselage; skids for landing gear; required catapult launch; engine behind pilot & passenger; giant chain-driven propellors; inefficient twin rudders and elevators; canard elevators (in front of plane; blocking pilot's view). Slow (45mph) and very awkward to fly. |

The Curtiss Pusher right: gasoline engine; ailerons for roll-control; horizontal and vertical stabilizers on the tail; tricycle-wheels landing gear (though too far ahead of its time). wrong: pusher engine/propellor behind the pilot; no fuselage; rudder & elevators in front of the pilot, ailerons placed between the wings, rather than on them; tricycle landing gear (too dainty for the rough landing fields of the day). |

The means for controlling airplanes were nearly as diverse as the number of airplanes, and some of the controls were perversely counter-intuitive (not helpful in an emergency). Landing gear was of every variety imaginable, and most did not work well on any but the most forgiving surfaces. In a day when there were no airports, landing (or even taking off) in a rough, open field was often enough to tip the plane on its nose, or worse.

The finicky engine/propellor systems of early aeroplanes were prone to failure -- sometimes catastrophic -- as when one of the giant wooden propellors on a Wright biplane shattered, causing a chain-reaction that sent the Wright plane into the first fatal crash (shown at right), killing the passenger.

The finicky engine/propellor systems of early aeroplanes were prone to failure -- sometimes catastrophic -- as when one of the giant wooden propellors on a Wright biplane shattered, causing a chain-reaction that sent the Wright plane into the first fatal crash (shown at right), killing the passenger.

On most early planes, the pilot sat in the open, with no protection, creating drag and even obstructing cooling airflow to the engine. Many early planes had engines mounted behind the pilot with "pusher" propellors pointed behind the plane; in a crash (even minor impacts) the heavy engines commonly ripped loose from the plane and smashed into the pilot in front. As a result, serious accidents in early aeroplanes were too-commonly lethal.

The Bleriot monoplane (below, left) overcame many of these shortcomings with the most important package of advances gathered into one airplane -- with the fewest design mistakes.

It is important to note that most of the important features of Bleriot's Model XI originated with other aircraft, mostly by other designers. But Bleriot -- better than anyone of his time -- had sorted through the countless aeroplane design options, and successfully incorporated most of the best ideas into one complete, practical airplane design. And that made all the difference.

The Bleriot XI, though imperfect, became THE defining airplane of the 20th Century. Its innovation of front-mounted, tractor-propellor engines reduced the fatalities caused by rear-mounted, pusher-propellor engines. The efficiency, reliability and safety of aircraft propulsion grew rapidly once the Bleriot showed the way. With its lightweight air-cooled engine (spared the heavy water-jacket, radiator, water pump and plumbing of water-cooled engines), and with the propellor bolted directly to the engine's turning parts, the Bleriot greatly increased engine/propellor performance, efficiency and safety.

The Bleriot XI, though imperfect, became THE defining airplane of the 20th Century. Its innovation of front-mounted, tractor-propellor engines reduced the fatalities caused by rear-mounted, pusher-propellor engines. The efficiency, reliability and safety of aircraft propulsion grew rapidly once the Bleriot showed the way. With its lightweight air-cooled engine (spared the heavy water-jacket, radiator, water pump and plumbing of water-cooled engines), and with the propellor bolted directly to the engine's turning parts, the Bleriot greatly increased engine/propellor performance, efficiency and safety.

Louis Bleriot's influence echoes still in most airplanes built today -- streamlined central fuselages, monoplane wings, yaw and pitch controlled by conventional tail surfaces and relatively normal flight controls -- in aircraft ranging from ultralights and bushplanes to airliners and jet fighters.

The Bleriot Model XI (above, left) had a host of credible competition -- but none quite so clean and so right, and so credible and so available. Too many important issues were unsettled about how to design airplanes -- until the Bleriot XI, with everything in the right place, carried its inventor across the English Channel, and itself onto the world stage.

Return to

Return to