Return to

Return toAviation History & Industry

main information page

Return to

Return toAviation History & Industry main information page |

Airbus A380,

|

|

It's official: the biggest airliner in the sky is no longer American. It's now the European double-decker Airbus A380 (originally known as the A3XX). On Wednesday morning, April 26th, before a cheering crowd of 30,000 at Blangnac field, the first prototype of the 4-engined, 460-ton (test-weight) aircraft -- the biggest airliner ever built -- accelerated to a takeoff speed of 170 miles per hour, and swept into the clear blue skies over Airbus's home of Toulouse, France, for its maiden flight.

After a four-hour flight across southern France, pilot Claude Lelaie extended the flaps, and did a slow fly-by over the Blagnac airport runway, before arcing around for final approach, and landing the behemoth on 22 oversized tires -- back onto the pavement from which, 36 years earlier, the supersonic Concorde first flew.

The A380's crew of six never needed the parachutes they'd strapped on before the flight. A380 chief test pilot Jacques Rosay offered the traditional, glowing, first-flight review: "You handle [it] as you handle a bicycle. It's very, very easy to fly." The flight was "extremely comfortable," added Engineer Fernando Alon.

With more than a 75-yard wingspan (239 feet), and two complete passenger decks running the length of the plane, the giant A380 dwarfs even the biggest Boeing 747 -- by over 100 tons. And it dwarfs any undertaking ever by Airbus. But now "shareholders can sleep better at night," says A380 chief flight engineer Gerard Desbois.

Built by Airbus, a consortium of European aircraft manufacturers, the A380 represents the "magnificent result of European industrial cooperation,"said French President Jacques Chirac. Airbus chief executive Noel Forgeard characterizes the A380 as "a fantastic collective effort between all the designers within Europe," but cautioned that "we have months and months of flight tests before we can begin our commercial service in the second half of 2006."

Boeing promises a "747 Advanced," but no airline seems too excited, and 747 sales have dwindled for several years, as long-haul airlines shift to the smaller, more-efficient Boeing 777 and Airbus A340.

BOEING BOUNCES BACK

Boeing, however, acts unimpressed by the A380's flight. Boeing spokesman Jim Condelles dismisses the giant Airbus as "a very large airplane for a very small market." With recent major orders for its competing future plane, the Boeing 787/7E7 Dreamliner, Boeing seemed confident that their smaller plane had found the bigger market. Earlier in the month, Boeing sealed deals with Air Canada and Air India for a total of over 80 planes, half of them 787s.

Investors, too, seemingly are focused on Boeing's future, and coldly dismissing the Airbus A380's debut. At the end of stock-trading on the day of A380's first flight, shares of Airbus' two owners (Airbus's 80% owner, EADS -- European Aeronautic Defense & Space Co. -- and British Aerospace's BAe Systems PLC) both actually posted slight drops. On the same day, underscoring the point, the New York Stock Exchange recorded the highest prices for Boeing stocks since 2003. (That was the year when Airbus surpassed Boeing as the world's top-selling brand of airliner, in units sold.)

FUTURE FLIGHT

Boeing's Bell cited the current trend in airline customers "focused on point-to-point travel" -- flying non-stop, direct, from origin to destination -- rather than the hub-to-hub travel for which the A380 is designed. Hub-to-hub requires most passengers to board small-airliner regional/"feeder" flights to reach the first hub airport (where large groups of passengers gather to board the A380) then change planes to the A380 and ride it to another hub airport, then again board a connecting small-airliner flight to reach their ultimate destination.

However, although the need for connecting flights undermines the cost-effectiveness and convenience of the super-jumbo, Airbus (and some of its customers) are betting that the A380 will be used heavily by customers commuting just between the hub cities. A lot of folks in big cities are simply flying to other big cities -- and the numbers of such passengers are increasing, as world population concentrates in the largest cities, at an accelerating pace.

The United Nations Center for Human Settlements reports that over 300 million people (more than the population of the whole United States) already live in the world's 50 largest cities -- and within 25 years most people will live in urban centers. Since the Boeing 747 is still in production after 25 years, that kind of "distant" future may be a rational planning basis for the A380. Growth is fastest in the underdeveloped nations, especially in cities with over 10 million people. As the global economy brings a rapidly rising standard of living to many of these those far-flung corners of the world, their super-cities may well justify Airbus's continent-connecting super-jumbo.

BOEING'S BACKYARD BATTLE-PLAN

In the short term, though, Boeing's direct-flight vision seems validated by the recent explosive growth in "regional" airliners -- particularly in the United States and Europe, where most of the world's commercial flights occur. Here, cities are expected to grow slowly over the next quarter-century.

Increasingly, Euro/American passengers are boarding short/medium range "regional" jets (like the Bombardier CRJ and Embraer 145), to fly directly to and from smaller cities -- bypassing the hubs. Now, "super-regional" jetliners -- growing in numbers, size and range -- are stretching into 100-150 seat aircraft with transcontinental range, and supplanting many of the narrow-body and jumbo-jetliners of the major airlines.

Boeing's 787 -- mating super-regional jetliner flexibility to jumbo-jet efficiency -- is designed for 200-seat to 300-seat loads, in medium/long-range, point-to-point travel. These characteristics make the 787 a challenger to the aging Airbus A300 and derivatives, as well as Boeing's own 757 and 767. Why compete with one's own planes? Boeing faces a glut of used jetliners on the market, including an overabundance of used 757s and 767s, which discourage sales of new 757s and 767s.

Boeing boss Bell claims the 787/7E7 will provide "30% greater efficiency than the 767, and [be] 20% more efficient than any of the [current] competition." If Airbus remains focused on developing its super-jumbo, rather than refining the efficiency of its medium-size jets, Boeing could well gain a growing share of Airbus' traditional key market segment, and pass it by.

U.S. law may be motivating Airbus and Boeing to look to different markets, too. America's Foreign Corrupt Practices Act ("FCPA") punishes bribery in seeking foreign contracts -- putting Boeing at a severe disadvantage to Airbus in the often-corrupt dealings of many developing nations. Though burned by its own corruption scandal at home (over military tanker sales), a contrite Boeing seems to be focusing more on the U.S. and Europe, where a free press thwarts or threatens most corruption.

ORDERS AND SALES -- AND COSTS

ORDERS AND SALES -- AND COSTS

To underscore Boeing's comparative progress, Boeing's Bell noted that the A380 debuted "5 years ago, and has 135 orders; the 787 was started a year ago, and has 235 orders." Airbus has indicated that it will break-even on the giant A380's massive development costs only after it sells about 250 of them, though others have suggested double that amount or more. Already the project is $2 billion over budget (at $16 billion), according to a BBC News report. Boeing's much-smaller 787 should cost less to develop, and require fewer sales to turn a profit, but will also be quite costly -- and not ready until 2007 (a comparable Airbus "A350" isn't expected until 2010). Still, airlines have placed over 200 orders for the 787.

Both the A380 and the 787/7E7 face a common problem on the ground, though: a shortage of concrete.

Boeing's 787/7E7 faces another problem: smaller, more-numerous jetliners -- flying "point-to-point" -- potentially creates a huge traffic demand at airports that simply don't have room for that many large planes coming and going. Though direct flights may be more efficient on paper, will airports at cities like Colorado Springs and Little Rock really be up to the traffic of a bevy of Boeings, bouncing back and forth? And how will the neighbors feel about the new noise? Finally, could all these new, long routes create chaos for the already-tangled air traffic control systems of America and Europe?

JUMBO-JET HISTORY

The A380's massive payload offers the promise of very cheap operating costs, per seat, per mile (per "seat-mile") -- the original purpose for creating the giant "jumbo-jets" of the 70's and 80's. Back then, when narrow-body airliners were common, airlines discovered that -- by packing triple the number of people into a bigger plane, with only about double the exterior size (and drag) of the smaller jetliners, and fewer crews to pay, and fewer engines and airframes to maintain -- airlines could cut operating costs sharply.

As airlines began flying their more-efficient "jumbo jets," ticket prices tumbled, especially on long routes. Occasional airline flights became affordable for the ordinary European or American -- and for many more of the world's people.

The wide-body "jumbo-jet" trend started with the giant, four-engined Boeing 747 (left) -- packing up to 625 people, in some versions. Boeing, seeking the same speed as its popular, pioneering Boeing 707 jetliner, built the 747 to carry three times as many passengers (in double-aisle "wide-body" cabins) -- without tripling the plane's exterior size (and drag), nor its resulting thrust and fuel needs.

The wide-body "jumbo-jet" trend started with the giant, four-engined Boeing 747 (left) -- packing up to 625 people, in some versions. Boeing, seeking the same speed as its popular, pioneering Boeing 707 jetliner, built the 747 to carry three times as many passengers (in double-aisle "wide-body" cabins) -- without tripling the plane's exterior size (and drag), nor its resulting thrust and fuel needs.

Giant "high-bypass" turbofans improved efficiency further. Triple the seats (and double the range) were gained for much less than triple the power and price. The obvious reductions in operating costs were further increased by the elminating of two-thirds of the cockpit crews (one plane, versus three), and similar reductions in many other expenses.

Boeing's 747 revolutionized the affordability of long-distance air travel.

Douglas Aircraft (soon merged into McDonnell-Douglas) tried to catch up to Boeing with its slightly smaller, triple-engined DC-10 jumbo-jet (below, left), and Lockheed produced its very similar L1011 TriStar jumbo. Each were plagued with teething problems, and the DC-10 gained unhappy notoriety for some horrible crashes, including some attributed (rightly or wrongly) to its design.

Lockheed -- new to the jetliner business (its last airliner was the ill-fated 1950's-era Electra turboprop) -- had a hard time getting traction in the 1970's jetliner market. Neither of the triple-engine widebodies lasted more than a couple of decades (both particularly plagued by the birth of Airbus).

Lockheed -- new to the jetliner business (its last airliner was the ill-fated 1950's-era Electra turboprop) -- had a hard time getting traction in the 1970's jetliner market. Neither of the triple-engine widebodies lasted more than a couple of decades (both particularly plagued by the birth of Airbus).

But Boeing's 747 -- the biggest, fastest, and longest-range of the world's mass-produced jetliners -- continued to sell, in countless variations (as it still does, intermittently, to this day).

With only two engines, the "mini-jumbo" A300 cost much less to buy and maintain than the big American jumbos, and offered greater operating flexibility (247-375 seats, to be exact, depending on configuration, and requiring less concrete -- permitting operation from many more airports).

Boeing responded, at first, with stretched models of its 727 and 737 narrow-body jetliners (and McDonnell-Douglas did the same with its DC-9/MD-80 family) -- and larger, more-efficient engines were fitted to the 737 and to McDonnell-Douglas's planes. But soon the pressure for bigger planes, fully in the Airbus class, forced Boeing to create the medium-range, 200-seat 757, and the long-ranging, 300-seat 767.

Competitor McDonnell-Douglas, however, was unable to develop a practical mid-sized jetliner -- between its DC-9/MD-80/MD-90 narrow-body and its giant triple-engined DC-10/MD-11 jumbo -- and gave up the fight, selling out to Boeing. Lockheed gave up on the airliner business altogether.

Airbus, meanwhile, continued to expand globally, presenting a challenge to Boeing everywhere -- including in Boeing's backyard, as major American airlines, and trend-setting low-cost carriers (LCC's), began turning to Airbus.

The Airbus line stretched into the 330-seat twin-engined A330, and its ocean-spanning, 4-engined variant, the A340, seating 260-440.

Airbus, meanwhile, continued to expand globally, presenting a challenge to Boeing everywhere -- including in Boeing's backyard, as major American airlines, and trend-setting low-cost carriers (LCC's), began turning to Airbus.

The Airbus line stretched into the 330-seat twin-engined A330, and its ocean-spanning, 4-engined variant, the A340, seating 260-440.

Boeing countered with a modern, efficient, long-range jumbo -- the massive twin-engined 777, seating up to 375 passengers. But Boeing kept building the 747 to carry the biggest passenger loads.

Boeing countered with a modern, efficient, long-range jumbo -- the massive twin-engined 777, seating up to 375 passengers. But Boeing kept building the 747 to carry the biggest passenger loads.

Airbus, however, also turned its sights on the narrow-body market (enlarged in recent years by low-cost carriers using American narrow-body jets). The resulting A320, and its derivatives, have eaten into the Boeing 737's market share, and drove a final nail into McDonnell-Douglas's coffin.

|

|

|

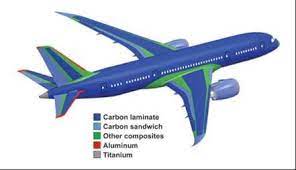

Airbus A380 composite materials distribution (FAA.gov) |

Apart from the market forces driving it, the A380 seems to be Airbus's way of finishing its drive to supplant Boeing as the world's dominant player in airliner manufacturing. (Last year, Airbus finally surpassed Boeing in sales). With the grounding of the world's fastest jetliner, the Anglo-French supersonic Concorde, Europe seemed eager for an opportunity to find a way to again top the Americans -- and the A380, much bigger than the 747, seemed like the way for Europe to beat America, again.

When the plane was unveiled earlier this year -- in the presence of British Prime Minister Tony Blair, German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder and Spanish Prime Minister Luis Zapatero -- French President Jacques Chirac declared the event "is for all of us a moment of emotion and pride," telling Airbus workers "Your adventure is a great success for Europe."

Consequently, it comes as no surprise that European governments are alleged (by Boeing) to be providing illegal subsidies to Airbus -- in violation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). For their part, the Europeans are charging that the American government has given similar favors to Boeing -- and the World Trade Organization's court will likely get a shot at straightening out this industrial dogfight.

However, the A380 may echo the Concorde's market failure, if the increasing market drive of recent years -- towards the point-to-point travel -- puts the airliner market back squarely in Boeing's pocket. But for now, Boeing's "Dreamliner" is just a dream, and there is no denying that the world's biggest flying jetliner is now a European aircraft -- the Airbus A380.

~ RH

Airbus A380 Specifications (Airbus.com)

Largest Passenger Jet Makes First Flight

(Washington Post, 4-28-05)

Uplifting day for Airbus

(Associated Press / Seattle Times, 4-28-05)

Airbus A380 Takes First Flight: A Titan Takes Flight

(Aviation Week & Space Technology, 5-1-05)

Largest Passenger Jet Ever Completes Maiden Flight

(New York Times, International Herald-Tribune)

World's Biggest Airliner Completes Maiden Flight

(Reuters, 4-27-05)

'Magnificent' superjumbo takes to the sky without a hitch

(London Telegraph, 4-28-05)

Boeing Catches A Tailwind

(Business Week 2-28-05)

Spate of Orders Boosts Boeing

(Washington Post, 4-27-05)

European Market Movers:

STMicroelectronics Falls; EADS is lower on news of Boeing orders

(Business Week 4-27-05)

"Aerospace giant EADS, the parent of Airbus, was down 0.53 to 22.04, after the Airbus A380's maiden flight."

Airbus confirms super-jumbo delay

(BBC NEWS - Business, 6-1-05)

After 4 Years in the Rear, Boeing Set to Jet Past Airbus

(Wall Street Journal, 6-10-05, excerpted in Daily Dose of Optimism)

Boeing's Duel with Complacency

(Business Week, 6-16-05)

(interview with Boeing Chairman Lewis Platt about Boeing & Airbus subsidies, scandals, CEOs, orders)

Another Turbulent Paris Air Show

(Business Week, 6-13-05)

Jetmakers: Better Flying Conditions?

(Business Week, 6-17-05)

Boeing's Plastic Dream Machine

(Business Week, 6-20-05)

"Major Screwup" at Airbus

(Business Week, 6-30-06)

|

Sept. 5, 2006:

Boeing, with 350 orders to date for its 787 Dreamliner, however, also has problems. Planned first deliveries may not make the 2008 deadline, owing to a host of problems. To start with, Boeing -- after dumping some of its legacy divisions, or turning them into quasi-independent subcontractors (disabling their union contracts) -- has attempted to outsource manufacture of 80% of the airplane, including the main sections: the fuselage and wings.

Attempts to lighten the 787 to meet performance and efficiency goals have resulted in carbon-fiber wings that are too heavy, and a fuselage that fails during testing. The exceptional diversity of vendors has resulted in mismatching problems, including mis-communication, software incompatibilities, and even counter-productive rivalries between vendors. General design chaos and management complications have created considerable friction inside the project.

|

Oct. 4, 2007:

See:

Feb. 14, 2019 news:

(suggested by Air Transport Digest of Aviation Week): "A number of airlines have recently announced the retirement of iconic aircraft, including the Boeing 747 [and Airbus A380]." (also at: https://blueskypit.com/2020/08/10/airlines-bid-early-farewell-to-iconic-jumbo-jets/ .) also: October 12, 2021 interviews:

(Executives close to the program discuss the A380's rise and fall.) by Jens Flottau |

Click here to return to the top