Return to

Return toAviation Answer-Man

Gateway

Return to

Return to

Aviation Answer-Man

Gateway

Return to

Return to

Aeronca/Champion History:

Beyond the Bathtub -- Chiefs, Champs & Citabrias

Copyright 2003-2004, 2016 (revised) by Richard Harris

Condensed from articles first appearing in In Flight USA, 2003-2004

(The updated and expanded version appears in the

Summer 2007 issue

of

AAHS Journal

)

This is the story of Aeronca (pronounced "uh-RON-kuh"), first big builder of the popular personal "puddle-jumpers." Unlike other light plane makers, Aeronca was not so much the product of a

single formative aviator or family, but the product of many diverse and changing hands, moving the company forward. Responding constantly to change in the market, Aeronca survives the longest of any of the traditional rag-wing plane-makers -- ultimately creating one of the most enduring and popular aircraft designs of all time.

Aeronca's long design evolution stretched from the early "flying bathtub" C-2/C-3, (left) to the modern, aluminum, tricycle geared "Chum" (right). While the rest of general aviation headed towards the "modern" design -- Aeronca would wind up returning to basic design ideas of the C-3 -- eventually producing one of the most popular personal planes ever. And would you believe Aeronca built jets? And was a force in the race to space? Read on.... (Aeronca/Todd Trainor photo, from www.Aeronca.com)

The First Popular Personal Plane

In 1927, Charles Lindbergh's famous trans-Atlantic hop stirred up a national aviation craze. Though Lindy wasn't first to cross the Atlantic, he was the first to make it solo, non-stop -- and even did it with a single wing and single engine. That suddenly made flying seem safer and more practical than it had ever seemed before. Lindbergh's sudden glory made every American want to become an aviator. The exploding interest in aviation drew businessmen's attention, nationwide. Five of Ohio's leading businessmen, and Robert A. Taft, the son of former U.S. President William Howard Taft (an Ohioan), and H.V. Fetick, the manager of the Taft family estate, optimistically formed the grandly named "Aeronautical Corporation of America" (eventually known simply as "Aeronca") in Cincinnatti -- with absolutely nothing "aeronautical" to sell.

Cincinnatti aviation entrepreneur Conrad Dietz hooked them up with French-born Jean Roche -- the Army's chief civilian aeronautical engineer, based at the Army's McCook Field, near Dayton. In his spare time, with colleagues from McCook Field, Roche had concocted a tiny single-seat personal plane that could be cheaply built and sold. With a simple triangular fuselage structure and wire-braced wings, wrapped in fabric, it was among the first to use a wing with the versatile Clark-Y airfoil shape (greatly rounded on top, flat on the bottom, with very rounded leading edge). The resulting tiny single-seat "Flying Flivver" was a gentle, well-mannered craft, stable and easily mastered, landing at 30-35mph, cruising 50-60mph. It was pulled along by a tiny two-cylinder 26-hp engine, crafted from sheet metal by Harold Morehouse (later a key engineer for Continental and Lycoming).

For company stock and a seat on the board of directors, Jean Roche sold his design to the Aeronca folk. He returned to Army duties, handing off the design to McCook Field engineers Roy Poole and Robert Galloway, who crafted a production version of Morehouse's little engine. With a 400-hour TBO (flight-Time Between Overhauls), their first 26-hp "E-107" engine, was quite reliable for its time. They refined the tiny plane for mass-production at Cincinnatti's Lunken Airport, with help from local aeronautics expert Roger Schlemmer.

The resulting "C-2 Scout" arrived on the scene in 1929 -- just as the stock market collapsed, and America plunged into the financial abyss of the Great Depression.

The resulting "C-2 Scout" arrived on the scene in 1929 -- just as the stock market collapsed, and America plunged into the financial abyss of the Great Depression.

Major airplane manufacturers staggered -- most collapsing in the face of incredibly tight markets. But little Aeronca flourished. Its cheap, homely little "toy" airplane (jokingly known as the "Flying Bathtub," for its shape) was just about the only airplane that could be afforded by a substantial number of people. It cost about a year's salary, and could be flown for as little as a penny a mile. The C-2 became the first truly successful "personal" airplane. Over 160 sold in just two and a half years, and created a new aircraft market: personal planes.

Early 2-Seat Aeroncas

C-2 sales soon faded, though. Personal-plane buyers wanted to carry passengers (without resorting to stuffing them behind the C-2's single seat, as was too-often done). And financially-strapped flight schools needed a cheap trainer. Over Roche's objections, Aeronca heeded the market's cries, and widened the C-2 into the two-seat "C -3 Collegian" (shown in the picture above, at left) -- while enlarging the single-ignition, two-cylinder engine into the 40-hp E-113. Over the next five years, over 450 C-3s were sold, firmly establishing the idea of the personal airplane and the cheap trainer.

But the C-3 lacked certain amenities, like comfort, good visibility, dual controls, and rough-field landing gear. Superior competitors were appearing.

Big Competition in Small Package:

Big Competition in Small Package:

The Piper Cub

By 1935, the

Piper Cub (right) was overtaking the C-3.

Though starting out slowly in the market, the Cub was a cleaner, roomier plane, with better visibility, more power, and more speed. Its longer landing gear allowed safer, easier operation from rough fields (as most flying fields were in those days).

The little Morehouse/Aeronca engine design had reached its practical limits at 40 horsepower, while the Cub's Continental A-40, though cantankerous, had plenty of room to grow. Further, the Aeronca used only external wire-bracing to hold the wing in place -- a practice outlawed in 1934. New designs would have to be fundamentally different.

As the personal/trainer market shifted to the Cub, Aeronca knew it needed to change. The C-1 Cadet -- an attempt to put pizzaz into the single-seat C-2 by giving it the bigger engine of the C-3 -- was too little, too late. Worse, Aeronca promoter Conrad Dietz died when the C-1 prototype crashed. And Aeronca's original designers had wandered away.

Aeronca's aging owners handed off the company to an Ohio real estate tycoon, Walter Friedlander, who wanted to set his sons up in the airplane industry. The new family management, with limited aviation experience, made up for it with enthusiasm, passionate attention to the company, and sensitivity to the changing market.

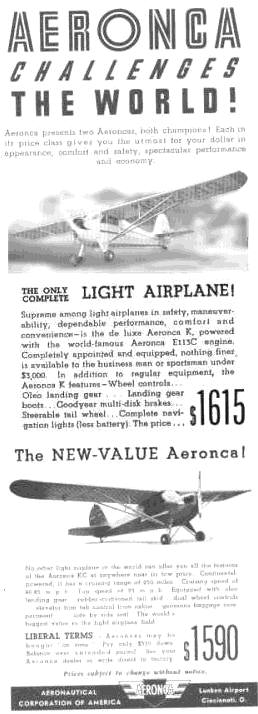

Roger Schlemmer, now Aeronca's chief engineer, faced the challenge of modernization. For easier landings on rough fields, he stretched the C-3's landing gear out, with separate "oleo" (air-oil) shock absorbers. In-flight wing-collapses of stunting Aeroncas (and the simliar Buhl Bull-Pup) had led to an outlawing of their wire-braced, pylon-supported wing design -- so Schlemmer switched to a wireless, internally-strong, strut-braced wing, and raised it (and the pilot) to a more conventional position. The resulting Model K was a far more attractive, easy-flying and comfortable plane, managing performance similar to the C-3, using the same little Aeronca E-113 engine. Niggling detail problems, though, would keep the K from production for over a year.

L is for Lake Lunken

Meanwhile, Schlemmer had become fascinated with the latest rage in airplane design: the clean, unbraced, "cantilever" wing. With no struts dragging in the breeze, it was aerodynamically cleaner, and theoretically faster, than traditional externally-braced wings.

Only a few planes had succeeded with cantilever wings -- most notably Fokker's successful single-engine and tri-motor airliners, and Cessna's trim Model A cabin monoplane. From Germany, came the Junkers monoplanes -- mid-way between the 4-seat Cessna and the 12-seat Fokkers -- distinguished by a low wing and corrugated aluminium skin.

Each of these planes were making great strides in their respective classes, and becoming powerful, popular icons of performance, efficiency and value. Airlines were flocking to the Junkers and Fokker designs, and the Cessnas were selling like hotcakes.

Schlemmer decided to take Aeronca forward with a streamlined, cantilever low-wing, two-seater, powered by the Aeronca engine. With long, clean strutless wings, that tapered towards their tips, and streamlined "wheel pants" enclosing the landing gear struts and half of the wheels, the new Aeronca design was a sharp shape. In no time at all, Schlemmer had a flying prototype. The resulting Aeronca L, however -- powered with only the tiny Aeronca E-113 engine (maxxed out to 42 hp) -- couldn't get a full load of fuel and two people off the ground.

|

| Model L (Model LB) photo by Bill Larkins, from Wikimedia Commons (click on this link for enlarged image, or right-click on photo and select "Show Picture") |

The Depression-strapped public, however, was slow to embrace the rather peculiar, pricey, personal plane.

And then came the flood. In January, 1937, the Ohio River -- which surrounded the Aeronca factory and half of Lunken Airport -- crested in one of the worst American floods in living memory, overflowing the dikes that had kept Lunken Airport dry. Aeronca workers scrambled to clear out all that they could save, and unfinished planes were hastily rigged for flight to higher ground.

But not all was saved. In a matter of hours, Lunken was sunken -- under 30 feet of water. A vast lake was all there was to see of America's largest airport. Only the roof of Aeronca's factory remained visible. When the waters subsided, Aeronca's buildings remained intact, but their precious contents -- partially-completed airframes, production machinery, supplies and many documents -- were a jumbled, ruined mess.

New town, old plane

The Friedlanders rebuilt, but did so on higher ground, away from flood-vulnerable Lunken -- setting in Middletown, Ohio, 30 miles to the north. They discarded the futuristic, but faltering, Model L, and finished development of the traditional Model K.

(With Aeronca's abandonment of the LeBlond-powered Model L, LeBlond sold out to another major customer, Rearwin Aircraft of Kansas City, who renamed the LeBlond engines "Ken-Royce" (for Mr. Rearwin's sons), and fitted them to Rearwin planes, instead.)

The Model K -- a much larger, airplane than the C-3 -- was a lame performer, even with the Aeronca engine boosted to 42 horses. And it was impractical to boost the Aeronca engine design any further. So Aeronca did what most small-plane makers were doing: switched to four-cylinder, dual-ignition engines from Continental, Lycoming and Franklin -- most of them, ironically, developed from engine designs by Harold Morehouse, who had built the first Aeronca engine.

The KC Scout used the first hot item on the market, Continental A-40's. They were cantankerous and unreliable at first. Nevertheless, they had room for growth, and would soon grow into a 50-hp model, which boosted the KC Scout into the KCA Chief. With a series of Chiefs, the Aeronca line quickly grew into competitive traveling machines, ranging up to the 65-hp Continental-powered 65CA Super Chief of 1940 (85mph cruise, 300-mile range, 400-pound full-fuel payload). Over 1,200 Chiefs, of various versions, sold before World War II.

War Planes

Germany, Italy and Japan had been rearming throughout the 1930s, and building their air forces. They had also aggressively begun training military pilots. Germany and Italy, in particular, had begun training young people to fly in civilian programs that were rather obviously aimed at preparing youth to be future military pilots. By 1938, recognizing the rising militaristic threat abroad, President Franklin Roosevelt authorized a government-sponsored, flight-training program for young Americans -- eventually renamed the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) -- using light planes at dozens of flight schools, tech schools and colleges. The announced goal was 10,000 new "civilian" pilots a year.

By late 1939, World War II had already begun in Europe and East Asia, as Japan and Germany began the conquest of continents. The U.S. government -- under public pressure -- remained neutral. But it was becoming clear that the growing war, engulfing the world, would likely soon draw in the U.S. Before the U.S. ever entered the war, Germany and Japan each had over 20,000 battle-hardened combat pilots (one source indicates 60,000 German pilots by 1941). The U.S. had only about 10,000 trained peacetime military pilots. By mid-1940, the government was frantically training young Americans by the tens of thousands to become pilots, with the CPTP now funding and supervising hundreds of civilian flying schools, popping up all over the U.S., providing free training to boost the number of U.S. aviators who could be conscripted for military service when the U.S. entered the war.

The CPTP program, eventually aimed at producing over 20,000 pilots a year, required massive numbers of small airplanes -- more than ever before sold in the U.S. Piper Cubs were the dominant player, still, but Aeronca was #2, with 1,000 of its planes eventually put into training service.

To meet the heavy training usage, Aeronca built a radically modified version of the 65 Chief -- the 65TC Tandem / 65TAC Defender -- similar to Piper's Cub, with tandem seating, and a fourth longeron to strengthen the fuselage. With various engines by Continental, Lycoming and Franklin, over 400 were sold to the CPTP schools and to the military (or foreign allies) as trainers. Another 250 had the engines replaced with a third seat, yielding the TG-5 glider trainers, which would help prepare pilots to fly giant troop-filled invasion gliders.

To meet the heavy training usage, Aeronca built a radically modified version of the 65 Chief -- the 65TC Tandem / 65TAC Defender -- similar to Piper's Cub, with tandem seating, and a fourth longeron to strengthen the fuselage. With various engines by Continental, Lycoming and Franklin, over 400 were sold to the CPTP schools and to the military (or foreign allies) as trainers. Another 250 had the engines replaced with a third seat, yielding the TG-5 glider trainers, which would help prepare pilots to fly giant troop-filled invasion gliders.

The military had also decided to use puddle-jumpers like the Pipers and Aeroncas -- painted military green and known in the Army as "grasshoppers" -- to provide forward air support for ground forces. The resulting "Army Ground Forces aviation," again, used mostly Cubs. But Aeronca modified the Tandem/Defender with "greenhouse" windows all around, resulting in the L-3 Grasshopper (above, right).

Produced by the hundreds, and spread all across both the Pacific and European war zones, the L-3 saw extensive use -- including as an aerial commanders' observation platform, close-in reconnaisance aircraft, artillery spotting and fire control, emergency medical evacuation ambulance, small cargo and personnel transport, and half a dozen other tasks.

America's various makes of grasshopper planes (particularly Piper, Stinson and Aeronca) were cheap and numerous, requiring little maintenance, while operating from the crudest, smallest clearings. They gave a powerful level of aerial mobility and eagle-eye vision to American ground forces --

giving them an important advantage over enemy forces who had far fewer such aircraft.

Also during the war, the Aeronca company was tasked by the government with building other planes -- Fairchild PT-19 (and PT-23/PT-26) Cornell military trainers. (PT-23, of Jayhawk Wing of Commemorative Air Force, shown at left, below)

The huge, 200-horsepower, open-cockpit, military trainers -- largest planes ever built by Aeronca -- brought Aeronca more money, but also kept Aeronca confined to old-fashioned, frame-and-fabric airplanes, with wood-spar wings. That technology was suddenly being made obsolete, as World War II forced technology ahead at a lightning pace -- pushing airplane design technology towards sturdy, light, sleek and efficient aluminum-shell airplanes. The fabric-wrapped Aeroncas and Fairchilds were not the wave of the future, but the last gasp of the past.

The huge, 200-horsepower, open-cockpit, military trainers -- largest planes ever built by Aeronca -- brought Aeronca more money, but also kept Aeronca confined to old-fashioned, frame-and-fabric airplanes, with wood-spar wings. That technology was suddenly being made obsolete, as World War II forced technology ahead at a lightning pace -- pushing airplane design technology towards sturdy, light, sleek and efficient aluminum-shell airplanes. The fabric-wrapped Aeroncas and Fairchilds were not the wave of the future, but the last gasp of the past.

Other wartime light plane makers -- most notably Beech and Cessna -- were getting experience building aluminum aircraft, or major sections of them. But Aeronca's aluminum experience was limited to little more than building a few parts for the B-17 Flying Fortress bomber and the C-46 Commando transport.

Postwar Planes

The war was sure to be won soon, and the public, now very aviation-minded (thanks to a war that glorified aircraft), was expected to embrace the idea of the personal airplane. The government predicted 200,000 planes a year would be sold to private owners. Every lightplane maker began planning and developing some postwar product, even while still busily turning out warplanes. Aeronca's instinctive idea was to capitalize on their established products, and make more of the same.

|

| Melinda Hopper flies this pristine Aeronca 7AC Champ, shown here at their invitational appearance at the 2008 Kansas Flight Festival, in Wichita. |

As the war drew to a close, the Model 7 Champion (better known as the "Champ") -- a tandem trainer designed to take the postwar trainer market from Piper -- was produced. Aeronca engineer Ray Hermes designed the Champ to overcome all the shortcomings of the Piper Cub . The Champ allowed front-seat solos, was streamlined with a fully-cowled engine, had a better, tighter door, and roomier cabin, and much better visibility. The plane sold like crazy in 1946, as the 90-mph 7AC Champion, and began the one of the longest-selling, most popular light plane designs of all time. In 1946, alone, over 3,000 sold -- particularly to optimistic flying schools, training thousands of new students funded by the GI Bill.

By the end of the decade, over 7,000 Champs had sold. In one variant or another (larger engines, electrical systems, tricycle or spring-steel landing gear, strengthened for aerobatics, fitted for military use or cropdusting, etc.), the Champ would be revived again and again -- by Aeronca, by Champion Aircraft, by Bellanca Aircraft, and lately by American Champion Aircraft, who manufactures a Champ variation even today.

A New Chief

But the American public of the late 1940s still wanted something more sociable than tandem seating for personal flying. The side-by-side Chief idea was revived with the 11AC Chief (actually a side-by-side variant of the Champ, freeloading on the popular name of the pre-war Chief). With performance comparable to the 7AC, and pre-war Chiefs -- 85mph cruise, 320-lb payload, 330 mile range -- the 11AC was fairly popular and over 1,800 sold, along with a few hundred others with 85-90 horse engines.

But the postwar profusion of personal planes promptly plummeted. The 200,000-a-year planes-purchased projection was an illusion. Only 30,000 new personal aircraft sold in the first year after the war -- 1946 -- quickly saturating the market. And when the government dumped another 30,000 war-surplus planes on the market (including surplus Aeroncas and Fairchilds), at bargain prices, the lightplane makers found themselves unable to sell their new planes for what it cost to make them. Most lightplane makers went out of business.

Cessna and Beech survived with modern, efficient, fast and attractive aluminum-shell light planes (Cessna 120/140, left, and Beech Bonanza, right), setting the pace for the future of light aircraft.

Cessna and Beech survived with modern, efficient, fast and attractive aluminum-shell light planes (Cessna 120/140, left, and Beech Bonanza, right), setting the pace for the future of light aircraft.

But Piper and Aeronca stubbornly clung to old-fashioned steel-tube-and-fabric airplanes, surviving on their respective fortunes, size, reputation and dealer networks -- and their perfected mass-production. In fact, with a chain dragging airframes along a track through the factory, Aeronca had implemented an automotive-style moving assembly line for aircraft, to maximize efficiency and productivity -- apparently the first lightplane maker to have done that, and perhaps the first airplane maker of any kind to have done so. At one point in 1946, Aeronca was routinely cranking out up to 30 planes a day, peaking at a stunning 53 in a single day!

Adapting to the Market

But efficient manufacturing wasn't enough to win the battle with modern, shiny Cessnas and prolific Pipers. An efficient airplane was needed -- something faster for the money than the simple tube-and-rag puddle-jumpers.

Fred Weick successfully capitalized on the valuable lessons from his strange W-1 pusher-prop plane -- with this more conventional (but still revolutionary) ERCO Ercoupe -- nothing like the failed W-1 emulations by Aeronca and others. |

The resulting shiny, modern, all-metal Aeronca Model 12 Chum (shown at far right) didn't get far. It had so many teething problems that the company -- faced with a severely depressed market by the late 1940's -- gave up on the Chum, after building only two prototypes.

The resulting shiny, modern, all-metal Aeronca Model 12 Chum (shown at far right) didn't get far. It had so many teething problems that the company -- faced with a severely depressed market by the late 1940's -- gave up on the Chum, after building only two prototypes.Back to Basics

With various combinations of engines and accessories, the 7AC Champ was tweaked continually into improved versions, including the military L-16 observation plane, and the ultimate: the 7EC, with an electrical system, including a starter (previous Aeroncas had all been started by the risky and awkward business of hand-propping the engine, or by a yanking a mechanical lever in the cabin). But the changes didn't overcome the basic problems of superior competition, and a nearly bankrupt market.

By the late 1940s, the few remaining private aircraft buyers were most interested in 4-seaters -- either to haul families (this was the height of the postwar "baby boom"), or to transport businessmen and their colleagues.

Like Stinson, Taylorcraft and Luscombe, Aeronca produced a true four-seater, capable of hauling four full-sized adults and full fuel. Pulled by a 145-hp Continental, the resulting 15AC Sedan was a mixture of modern aluminum wings and conventional tube-and-rag fuselage, perched on conventional taildragger landing gear -- with modest performance (105 mph for just over 400 miles).

Cessna soon trumped that idea with its own four-seater, the aluminum shell Cessna 170, which traded in capacity -- you gave up a passenger or full fuel (shortening range) -- for speed (cruise speed of 120mph or more). With its sleek, all-metal construction, and competitive price, the Cessna became the pick of the personal pilot, and left the others behind. Stinson, Taylorcraft and Luscombe faded into oblivion, and in late 1951 the last official Aeronca airplane -- a 15AC Sedan -- was flown off to its customer.

Aeronca Successors

The Champ design would soon be handed off to Champion Aircraft of Oceola, Wisconsin. Starting in 1954, they produced the 7EC and a strengthened acrobatic version, the 7ECA Citabria ("airbatic" spelled backwards, pronounced "sit-TOBB-ree-ah"). Champion would also try selling tricycle-geared (7FC Tri-Traveler) and twin-engine versions (402 Lancer), as low-cost trainers, without much success. But the aerobatic Citabria lasted well into the early 1960s, and would eventually be revived in the 1970s, to become the basic beginners' "akro" plane for the rest of the century.

The Champ design would soon be handed off to Champion Aircraft of Oceola, Wisconsin. Starting in 1954, they produced the 7EC and a strengthened acrobatic version, the 7ECA Citabria ("airbatic" spelled backwards, pronounced "sit-TOBB-ree-ah"). Champion would also try selling tricycle-geared (7FC Tri-Traveler) and twin-engine versions (402 Lancer), as low-cost trainers, without much success. But the aerobatic Citabria lasted well into the early 1960s, and would eventually be revived in the 1970s, to become the basic beginners' "akro" plane for the rest of the century.

In the 1970s, the Champ would be revived, in various versions, by Bellanca (in neighboring Minnesota) as the Bellanca-Champion line. Bellanca produced the Citabria in various versions, and modified it into a sturdy competition-acrobatics plane with modified wings, called the 8KCAB Decathalon. For bush pilots, sportsmen, farmers and ranchers (typical Piper SuperCub customers), Bellanca also built a stout, 150-hp "land-anywhere" utility version of the Champ, the 8GCBC Scout -- even offering a cropdusting rig option.

Bellanca also tried (unsuccessfully) to revive interest in the basic Champ, as the 7ACA Champ fitted with a 2-cylinder Franklin engine, and no starter or electrical system, and no amenities -- priced at $4,995 as the "cheapest new plane in America," Turned out no one was that cheap, anymore.

Hoping to compete with the wildly popular two-seat, tricycle-gear Cessna 150 -- which was rapidly replacing the Piper Cub and Aeronca Champ (both "obsolete" taildraggers) as the universally preferred trainer plane -- Bellanca responded by developing a tricycle trainer based on the 11AC Chief. It only got as far as a flying prototype.

But the Champ remains a rather popular basic design idea. Today,

American Champion Aircraft

builds the 7ECA and other Champ derivatives, for pilots who like the fun and flexibility of an economical, acrobatic, rough-field taildragger.

Aeronca LIVES!

Contrary to popular assumption, Aeronca did not go out of business. In fact, it is doing quite well, thank you. But in 1951, with the Korean War having just begun, and the tensions of the "Cold War" with the Soviet Russia at their peak, America was pouring vast sums into military aircraft. Aeronca had discovered it could make more money, with less risk, by building parts of others' military aircraft. rather than building their own little civilian planes. So Aeronca ditched its own airplane line, and hitched its wagon to the Pentagon gravy-train.

Contrary to popular assumption, Aeronca did not go out of business. In fact, it is doing quite well, thank you. But in 1951, with the Korean War having just begun, and the tensions of the "Cold War" with the Soviet Russia at their peak, America was pouring vast sums into military aircraft. Aeronca had discovered it could make more money, with less risk, by building parts of others' military aircraft. rather than building their own little civilian planes. So Aeronca ditched its own airplane line, and hitched its wagon to the Pentagon gravy-train.

Aeronca built radomes and nacelles for the Boeing B-47 Stratojet bomber, massive wheel-well doors and elevators for the B-52 Stratofortress, and so on. Over the next few decades, the company would become an expert in high-temperature airframe parts, including thrust reversers, wings for the Mach 3 XB-70 Valkyrie, the outer shell of the Apollo space capsules and the Space Shuttle.

Aeronca built sections of Chinook helicopters and C-130 Hercules transports, wing ribs and fairings for the Boeing 747, and today builds parts for Airbus airliners.

Three times, though, Aeronca contemplated building whole aircraft, again:

Click here to return to the top

REFERENCES & SOURCES:- Collins, Leighton (former Aeronca factory salesman, and editor of Air Facts Magazine), "Traveling Salesman: Business Flying... In the 1930's" (partially recounting Aeronca history and experiences as Aeronca salesman), pp.164-168

- Garrison, Peter, "The Flight of N-X-211" (Lindbergh's transatlantic solo), pp.152-155

- Smith, Frank Kingston, "The Turbulent Decade" (historical analysis of general aviation "boom & bust" and renaissance, 1945-1955), pp.200-208

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Aeronca C-2

Aeronca C-3 'Flying Bathtub'

Aeronca Model K

Aeronca Chief family (prewar)

Fairchild PT-19A Cornell

Aeronca Arrow

Aeronca Chum

Aeronca 7AC/7EC Champion ("Champ") family

Aeronca 11AC Chief / 11CC Super Chief family (postwar)

Aeronca 15AC Sedan

Champion 7FC Tri-Traveler

Champion Lancer twin-trainer

Citabria/Decathalon/Scout family

Bellanca-Champion Trainer

(tricycle-geared 11AC Chief variant)

Bellanca-Champion 7AC Champ

Fox Jet

x