Return to

Return toAviation Answer-Man

Gateway

Return to

Return to

Aviation Answer-Man

Gateway

Return to

Return to

Chapter 1

Origins:

Pioneering on the Prairie

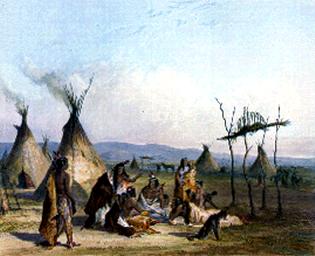

For 100 centuries or more, the confluence of the Big and Little Arkansas rivers (pronounced AR-kan-saw in the rest of the U.S., but pronounced "ar-KANSAS" by today's Kansans) provided a natural meeting place for animals and people. For hundreds -- probably thousands -- of years, many native Americans had roamed this area, and all the vast inland prairies of North America -- getting their subsistence from the massive herds of bison ("buffalo") that migrated across the grassy plains. Among these natives were the Kansa (also known as the Kaw) whose name meant "people of the south wind" -- a reference to the almost continual southerly winds that blast across the Kansas landscape, especially during the warm months. Other natives frequented the area, including the Wichita and the Osage who inhabited the area near the confluence of the Arkansas rivers.

That lifestyle and culture was invaded in the 1400's by an Italian explorer looking for a shortcut to China, who stumbled into the American continents on his way. Christoper Columbus was followed by a fistful of other explorers, and their hundreds of crewmen, who came with Papal blessing to conquer and plunder the virgin land and its technologically unsophisticated people, and force Christianity upon the land.

With helmets, armor, horses and firearms, the Spanish "conquistadors" ("conquerors") marched bravely and brazenly throughout the Americas, seizing anything -- or anyone -- that caught their fancy.

With helmets, armor, horses and firearms, the Spanish "conquistadors" ("conquerors") marched bravely and brazenly throughout the Americas, seizing anything -- or anyone -- that caught their fancy.

Among these invaders was Coronado (below, right), in search of a mythical city of gold -- Gran Quivira. In 1540-1541, led by a deceptive guide, Coronado marched his expedition of 300 soldiers north from present-day Mexico, through what is now Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas, in search of the golden city, before giving up and returning to Mexico.

What he found deep in the inner reaches of the continent, instead, were vast arid grasslands, cooked by 100-degree sun in the summer, tormented by violent storms in spring and fall, and frozen in the bitterly cold winters -- and torn daily by howling winds. He saw a land ripped by tornadoes, pounded by hail, and scorched by vast wildfires ignited by terrible electrical storms.

What he found deep in the inner reaches of the continent, instead, were vast arid grasslands, cooked by 100-degree sun in the summer, tormented by violent storms in spring and fall, and frozen in the bitterly cold winters -- and torn daily by howling winds. He saw a land ripped by tornadoes, pounded by hail, and scorched by vast wildfires ignited by terrible electrical storms.

Despairing of finding anything worthwhile, Coronado returned to the Mexican isthmus, and Spain -- never realizing he had been walking over brown gold the whole time: the greatest expanse of prime topsoil in the world, capable of producing the world's greatest supply of that most basic, essential and valuable commodity: food.

Thereafter -- although the native Americans (mistakenly labeled "Indians" by Columbus) were ruthlessly conquered, exploited, tormented and decimated by the Spaniards -- the Indians of the plains were lucky enough to be largely ignored by the Spanish.

Indeed, the Spanish brought the plains Indians their greatest asset: the horse. A few horses had been left behind by the Spanish, or had run off. They quickly prospered on the wide open plains, and mutiplied. The plains people promptly put them to work, providing the Indians with a whole new level of mobility -- for migration, for the hunt, and for battle.

Indeed, the Spanish brought the plains Indians their greatest asset: the horse. A few horses had been left behind by the Spanish, or had run off. They quickly prospered on the wide open plains, and mutiplied. The plains people promptly put them to work, providing the Indians with a whole new level of mobility -- for migration, for the hunt, and for battle.

But a couple of centuries later, the plains natives were not so lucky. English-Americans, and their African-American slaves and freedmen, began migrating westward across the North American continent from the original 13 American colonies. As they moved forward, they pushed the native Americans from the wild country, and began cultivating it. Eventually, the white migration -- following what it claimed was its "Manifest Destiny," and joined by African-Americans -- began invading the inland plains, stretching from the Dakota territory to the north, to Texas in the south.

At first, the invaders were only hunters, who sought merely to live off the bounty of the buffalo and other wild game, as the Indians before them. But they did so more recklessly and violently -- bringing rifles and horses, and slaughtering whole herds of bison merely for their hides -- which they exported to the cities back East -- and then, ultimately, merely for sport.

As the extinction of the buffalo neared completion, the vast open grassland became ripe for cattle grazing, and cattle herders moved in. The broad, open grasslands provided ideal free range for the cattle herders, who became a law unto themselves -- often claiming grazing rights to hundreds of square miles, and enforcing their claims with rifles and hired gunmen.

As the extinction of the buffalo neared completion, the vast open grassland became ripe for cattle grazing, and cattle herders moved in. The broad, open grasslands provided ideal free range for the cattle herders, who became a law unto themselves -- often claiming grazing rights to hundreds of square miles, and enforcing their claims with rifles and hired gunmen.

The tough cowboy, tall in the saddle, became America's mythical hero -- a frontier Superman -- able to tame a wild horse, then ride it from sunup to sundown, in all extremes of weather, cornering and lassoing renegade steers, battling wolves, rattlesnakes, outlaws and renegade Indians, and then arriving in a frontier town for a drink, a brawl, and a gunfight.

Not far behind the cowboys and cattle herds, following them slowly but surely, migrating by wagon train for protection, were the cattlemen's greatest enemies: the "sodbusters" -- prairie farmers eager to plow up the earth and plant wheat in its fertile topsoil.

To identify their territory and protect it from grazing by cattle, they put up fences. Despite politicking and pitched gun-battles, the cattlemen were pushed farther to the west and south by the unending tide of farmers seeking to claim the productivity of vast "homesteads" -- 150-acre government land-grants -- and prosper off the sweat of their brow and the bounty of the rich earth.

To identify their territory and protect it from grazing by cattle, they put up fences. Despite politicking and pitched gun-battles, the cattlemen were pushed farther to the west and south by the unending tide of farmers seeking to claim the productivity of vast "homesteads" -- 150-acre government land-grants -- and prosper off the sweat of their brow and the bounty of the rich earth.

Slowly, mile after mile, the fence lines crept ever westward, until halted in the 1850's, near the new Kansas-Missouri border, where slaveholders and abolitionists fought viciously for control of the destiny of the two new states. Slaveholders and abolitinists alike turned to mayhem and murder, each claiming God was on their side.

Slowly, mile after mile, the fence lines crept ever westward, until halted in the 1850's, near the new Kansas-Missouri border, where slaveholders and abolitionists fought viciously for control of the destiny of the two new states. Slaveholders and abolitinists alike turned to mayhem and murder, each claiming God was on their side.

The most famous of the combatants in "Bleeding Kansas" was John Brown (right), who led the massacre of five pro-slavery people in Ossawatomie Kansas -- one of the major incitements of the South against the North in the mid-1800's.

Brown's later raid on an armory at Harper's Ferry in West Virginia -- to steal arms for a slave rebellion -- was a polarizing event in the relations between the South and the North, and a song about him would become the North's anthem of the Civil War.

Brown's later raid on an armory at Harper's Ferry in West Virginia -- to steal arms for a slave rebellion -- was a polarizing event in the relations between the South and the North, and a song about him would become the North's anthem of the Civil War.

With the Congressional "Great Compromise" of 1850 -- which declared Missouri a slave state, and Kansas free, and pleased no one -- the tensions grew until the issue erupted into a civil war in 1861, in which America's North and South, for four bloody years, fought out their differences over states' rights and slavery -- which had first come to blood in "Bleeding Kansas." By 1865, the matters were settled, and westward expansion of immigrant America resumed -- free of slavery.

"Civilization" had only reached the eastern edge and northeastern corner of Kansas. The rest was still open grassland, where dwindling herds of buffalo remained. Here cattlemen kept trying to graze their growing herds, while battling with the plains Indians. But it was the plains Indians who suffered the most. They were starving for lack of buffalo, and the tiny bit of wild game remaining was no longer theirs. In addition to the competition from the white man, the plains Indians were faced with thousands of competing hungry Indians from other tribes, from back East and from the South, forced out onto the plains by the white man's government.

In the late 1860's, where the Big and Little Arkansas Rivers joined, there was just an Indian camp and trading post, where J.R. Mead, William Greiffenstein and Jesse Chisolm (himself half-Indian) traded with the Wichita and Osage Indians. Despite the native/immigrant tensions across the plains, these men generally fared well with the Indians. Mead would go on hunting expeditions, himself, gathering hides and tallow from the plentiful game, and selling it to people back east. Chisolm delivered goods to Indian settlements, in Oklahoma Territory -- returning with furs and hides -- along a path that came to be known as the "Chisolm Trail."

In the late 1860's, where the Big and Little Arkansas Rivers joined, there was just an Indian camp and trading post, where J.R. Mead, William Greiffenstein and Jesse Chisolm (himself half-Indian) traded with the Wichita and Osage Indians. Despite the native/immigrant tensions across the plains, these men generally fared well with the Indians. Mead would go on hunting expeditions, himself, gathering hides and tallow from the plentiful game, and selling it to people back east. Chisolm delivered goods to Indian settlements, in Oklahoma Territory -- returning with furs and hides -- along a path that came to be known as the "Chisolm Trail."

As the rail lines moved west, and reached the settlement known as "Wichita," vast herds of Texas longhorn cattle -- driven along the Chisolm Trail, from ranches in the American Southwest -- roamed through the streets of Wichita, being herded to the "railheads" (the end of the railroad lines) there, for shipment to America's hungry millions "back East." Wichita had become the principal gathering point for the Wild West's great cattle drives -- the largest migration of livestock in history -- where over 5 million cattle and a million horses would move over the next 20 years.

The rough-hewn cowboys, who came to town with the cattle, often acted less civilized than their herds -- drinking, carousing, brawling, shooting up each other and the town -- until Wichita's leaders hired as marshall Mike Meagher and deputized his brother John and a handful of deputies, including a buffalo-hunter named Wyatt Earp (below, left),

whose law-enforcement career, begun on the dusty cowtown streets of Wichita, would become an American legend. The Meagers, Earp and their deputies impounded the visiting drover's guns -- at the point of a shotgun when necessary -- until they left town.

whose law-enforcement career, begun on the dusty cowtown streets of Wichita, would become an American legend. The Meagers, Earp and their deputies impounded the visiting drover's guns -- at the point of a shotgun when necessary -- until they left town.

The town's bloody lawlessness began to subside, or at least to confine itself to the township of Delano, across the river (Delano would later become part of Wichita), where rowdy saloons and bordellos continued to cater to the cowboy crowd. (Over a century later, West Wichita still retains its reputation and flavor as the "redneck" side of town.)

As the new Kansas state government (founded in 1864) spread its organized territory westward -- surveying the land and setting up county boundaries and land parcels -- homesteading farmers were beginning to lay claim to the open rangeland, and fence it off for planting crops. They slowly replaced the "cowpokes" who had brought the cattle to market across open range.

With the fences moving westward, and finally engulfing Wichita's Sedgwick County,

the farmers brought their own cows, which were vulnerable to "Texas Fever" -- a disease spread by Texas longhorn cattle. The state legislature, chiefly beholden to the state's rapidly growing farmer population, expanded a quarrantine against the free-roaming Texas Longhorns that had brought Wichita so much wealth -- locking the cattle drives out of Sedgwick County. The rail lines moved westward, where the range land was still wild and free -- and the cattle drivers moved westward, to Dodge City, to meet the train outside the boundaries of the quarrantine.

the farmers brought their own cows, which were vulnerable to "Texas Fever" -- a disease spread by Texas longhorn cattle. The state legislature, chiefly beholden to the state's rapidly growing farmer population, expanded a quarrantine against the free-roaming Texas Longhorns that had brought Wichita so much wealth -- locking the cattle drives out of Sedgwick County. The rail lines moved westward, where the range land was still wild and free -- and the cattle drivers moved westward, to Dodge City, to meet the train outside the boundaries of the quarrantine.

With Wichita now largely tamed, some of the cops became crooks. Wyatt Earp turned on his political opponents, and arrested one rather roughly. The City Council sanctioned him, thanked him for his service, and sent him on his way -- to tame an even rowdier Dodge City, followed by a legendary gunfight in Tombstone, Arizona against outlaws at the O.K. Corral.

With Wichita now largely tamed, some of the cops became crooks. Wyatt Earp turned on his political opponents, and arrested one rather roughly. The City Council sanctioned him, thanked him for his service, and sent him on his way -- to tame an even rowdier Dodge City, followed by a legendary gunfight in Tombstone, Arizona against outlaws at the O.K. Corral.

Earp left Wichita just behind a fatherless Wichita teen, Henry McCarty -- who later, as a teenage fugitive gunslinger in New Mexico, changed his name to William H. Bonny... better known as "Billy the Kid." (Billy's mother, widow Catherine McCarty, who ran the City Laundry, was one of Wichita's "founding fathers," the sole female signature on the 1870 town charter).

As those tough, challenging guys cleared out, an even tougher woman with a hatchet, named Carrie Nation (right), came stomping into town to preach the gospel of "temperance" -- abstinence from alcohol -- while raiding bars with her army of righteously indignant, hatchet-wielding, Temperance Movement women.

Wichita was off to a rough start.

for

Chapter 2

The Turn of The Century:

The Money Rolls In

Click Here

In the next chapter, the dusty cow town brushes itself up into "the Peerless Princess of the Plains," with the industrious, civilizing influence of farmers -- who help Wichita recover from the loss of the cattle drives.

Bringing a new kind of gold to town, golden grain, they revive Wichita's fortunes, and set it on the path to power.

Bringing a new kind of gold to town, golden grain, they revive Wichita's fortunes, and set it on the path to power.

With the rail lines now picking up cattle in Dodge City, Wichita turns itself into an unloading point, turning the cattle into packed beef, again making Wichita a key source of America's beef.

W.C. Coleman lights up America's darkest corners, and - along with companies creating Metholatum, fence wire, razor blades, and railroad cars -- builds Wichita into one of the most sophisticated manufacturing towns west of the Mississippi.

Wichita gambles heavily on building new routes to and from the city -- and booms again as a hub of commerce. Grand buildings arise.

Wichita gambles heavily on building new routes to and from the city -- and booms again as a hub of commerce. Grand buildings arise.

A World War interrupts, and a sudden oil strike makes Wichita truly rich -- and brings in the area's first, least-known, and most important aviation pioneer: an iron-fisted oil-wildcatter named "Jake," who will change Wichita -- and aviation -- forever.

All this and more, in the next surprising chapter...

Return to

Return to

Return to

Return to

Aviation Answer-Man

Gateway