Background Note:

Child-Protection Changes in Kansas 1995-2004THE DETAILS

Last updated October 26, 2001

Last revised December 4, 2002

Partially updated and revised, July 30, 2004

PREVIEW:

In recent years, Kansas has been the nation's foremost battleground for radical, combative, new approaches to child protection and foster care. The battle has largely been between liberal, moderate and conservative hard-liners (and libertarian extremists) -- with the state's most vulnerable children, and their families, caught in the middle. The resulting horror stories have brought headlines and lawsuits -- and dramatic changes -- but little real reform.Read below for the details — then confirm them by reading the official documents, audit reports, and Kansas newspaper accounts, linked from additional pages of this website, or through private conversations with any current or former foster child.

A Sad State of Affairs:

Kansas Child-Protection Before the 1990's.

The Problem Comes to a Head:

The ACLU Lawsuit

The Fragile Truce:

The Lawsuit Settlement Agreement

Dodging the Issue:

"Privatization"

A Sad State of Affairs:

Kansas Child-Protection Before the 1990's.During the 1970's and 1980's -- as the issue of child abuse and neglect grew out of the war on poverty, feminism and other liberal causes -- the federal government and the states became actively interested in aggressive "child-protection."

In Kansas -- as in all states nationwide -- the Kansas child-protection bureaucracy underwent a massive growth, and with it came a massive intervention in family life, and a massive growth in the state's collection of foster children. Thousands of Kansas children were taken from their families, and put into orphanages and foster homes.

The conservative backlash of the 1980's further exacerbated the volume of interventions, as the "war on crime" and "war on drugs" resulted in an explosive growth in incarcerations of young parents, and sweeping collections of children -- even at birth -- from mothers suspected of alcohol and drug-abuse.

By the late 1980's, nationwide, half a million American children were in foster care. And among the states with the highest rates of child takings in the U.S., was Kansas.

But while the social workers, psychologists, lawyers and bureaucrats in the Kansas system commanded salaries "commensurate with their credentials," the children whom they were "protecting" commonly languished in situations no better than those from which they had been taken.

In Kansas, as everywhere else, the people most affected by the state's child-protection system were the people most powerless to affect it: the children. And the parents they were taken from, who were generally the poorest of the poor, were just about as powerless.

Under the system then in effect -- administered by the Children & Family Services Division of the Kansas Department of Social & Rehabilitation Services (SRS) -- state social workers for SRS were divided into two groups: Investigators and Case Managers.

The only real requirement for either position was a college degree in social work. And there was no shortage of applicants, as hundreds of idealistic young Kansas women saw the oppportunity to practice the powers of motherhood -- on a huge and powerful scale -- with a paycheck and office hours, instead of an unpaid, lifetime commitment to a single family.

SRS Investigators investigated families -- deciding which families to intervene in, and which children to take -- with generally routine approval from judges in secret judicial proceedings, in juvenile courts operated behind closed doors.

Then the selected children -- and their families -- were essentially turned over to an SRS Case Manager, who then managed the "services" imposed upon children -- and upon their families, if they wanted to be re-united with their lost children (which most did).

These "services" included

To understand these three "child-protection services" more clearly, review these definitions:

- Family Preservation

- Foster Care

- Adoption

- Family Preservation

-- family rehabilitation, actually -- (evaluations of home and family, parenting courses, individual therapy, family group therapy, supervised visitation and supervised living).In theory, family preservation programs were supposed to enable children to be returned home to their own "rehabilitated" families. Ironically, as a condition of "reunification," families were often required to break up (typically requiring a suspect family member to move out, or requiring the parents to divorce).

Despite a high rate of parental interest and cooperation, "family preservation programs," routinely were deemed failures -- often because the prescribed services were not provided in a "timely" manner, in spite of court instructions, or were sloppy, cheap and inadequate -- leaving families officially "inadequate" for their children's return when time ran out and the court was obliged to make permanent placement decisions.

and

- Foster Care

...was officially intended as temporary out-of-home placement (for the kids), putting them in the custody of someone else until they could be safely reunited with their families or adopted by someone else. In reality, foster care was (and is) the final placement for most children whom the state holds for more than a few weeks.Specifically, "foster care" can mean any one (or more) of a number of different types of placements for children in state custody, including:

- relatives

...(though usually with a proviso that the relatives may not let the children have contact with their own families. The most common placements are with a non-custodial parent or with a grandparent -- though these opportunities are very often ignored by the authorities. When children are taken from a custodial parent, even a non-offending, non-custodial parent with visitation rights must often resort to suing authorities to maintain the right to continue seeing their children.)- family friends

... (extremely rare)- strangers

..., who are licensed, paid foster parents

(commonly referred to as "foster parents," officially, these people are required to pass background checks, home inspections and personal evaluations by the state and/or its contractors, to complete specific parenting courses, and to attend continuing parenting education. However there is little data to indicate the extent to which any of these requirements have been met, and state auditors have found many cases where not even the required background checks have been done, which has resulted in a number of foster children being placed with convicted felons.)- a social worker

... (in very rare, short-term situations.)- a medical hospital

... (rare, typically for ill and premature infants, requiring long-term care)- orphanage

... (commonly referred to by various euphemisms, such as "group home," "children's home," "residential facility," etc.) These facilities can vary in size from a small group home with a half-dozen transient children (supervised by a single set of "house parents"), to a large "residential foster care center" with over 100 kids.

A high percentage of foster kids are placed in these facilities, particularly those who have just been taken from their parents, and those with special needs. Orphanges are also often the placements for children whom authorities want ready access to (such as kids whom authorities expect will soon be transferred by the court to highly restrictive placements, or returned home). But increasingly they've become all-purpose "storage facilities" for the growing numbers of children in state custody.

Orphange placements often last much, much longer than intended -- with many children spending most (or all) of their childhoods being shuffled from orphange to orphanage, until they rebel, and wind up in more restrictive placements, or run away.- disciplinary facility

... (an orphanage where living is highly regimented and controlled, typically with an elaborate disciplinary code, and threats of escalation to more restrictive placements if the child is not completely cooperative. A routine response to disciplinary problems)- "secure" facility

... (a low-security juvenile jail for children in foster care) — (a routine response to disciplinary problems, including runaways -- particularly those who attempt to return to their families. Secure facilities also routinely drug children to make them easier to manage.)- jail or prison ("correctional institution")

... (a common "solution" to problems with the hundreds of runaways from state custody. Also used as a routine disciplinary tool by many judges.

Many foster care providers have routinely sought -- or facilitated -- criminal prosecution of their most rebellious and challenging foster kids, as a way of dumping responsibliity for them.

Although "backyard brawling" -- common among adolescents -- normally results in grounding or loss of privileges in a normal home and family, for Kansas foster kids it very often results in criminal charges and incarceration.)

Under the state's new "juvenile justice" system, rebellious and difficult children in foster care are often transferred permanently to the custody of the juvenile justice system, allowing the SRS and annoyed foster-care contractors to "dump" them.- psychiatric facility

... -- usually under forcible confinement

(a routine response to disciplinary problems, and to children who refuse to see things the way their social workers and psychologists see them -- particularly assessments of their families.

An automatic response to any perception of suicidal tendencies. Also -- in some jurisdictions -- a common response to any indication or suspicion of drug or alchohol use.

Also, a common "end of the road" for kids who have been put on an extensive regimen of psychotropic medications, and do not seem to respond as intended by the people administering the drugs -- however jails are used nearly as routinely for such kids.)- "independent living" facility

(a loosely-supervised apartment complex, for a few highly-trusted older teens, intended as a transitional living preparation for emancipation from the state custody upon reaching 18, or earlier.

This program is commonly used as a way of removing pregnant teens from the system.

Since it promises greater autonomy, it is the placement most highly sought-after by teens in the system. Many foster girls see this option as a strong motivation to get pregnant.)- running away

..., while officially in state custody.

(Seldom reported on the official record, or hidden in other data categories, this has nevertheless been the actual "placement" for untold dozens -- probably hundreds -- of kids fleeing the foster care system.

On any given day, according to various sources in the system, anywhere from a dozen to a hundred kids or more cannot be accounted for in the system because their whereabouts is unknown, due to having run away, and not been subsequently located by authorities.

These children often attempt to return to their families Ironically, their families have commonly been threatened by authorities, in advance, with criminal prosecution if they take in their own runaway children -- or even if they fail to call the police, to turn in their runaway children.

If their parents insist on obeying the authorities, runaway children must then return to state custody to face harsh punishments, or struggle to live on the streets, or run away to whatever other people they can find, who will house and hide them (risking felony charges). Good, law-abiding citizens typically turn them away, or turn them in.

So do shelters for the homeless. This forces many state runaways to resort to living with criminals as the only way to stay on the run, and out of the hell of foster care. Rather than return to the torment of foster care, many become menial, criminal or sexual servants to their illegal hosts.

At any given moment, dozens (some say hundreds) of Kansas foster kids are on the run. Sources inside the system have indicated that "many" runaway kids are never found, and are simply taken off the books when their 18th birthday has passed.)

- Adoption

... was the final "service," if authorities decided to permanently take the children from their parents -- where the child would be permanently separated from their family, and put up for adoption (usually through a private adoption-service contractor).

However, most of Kansas' permanently-separated foster kids, placed officially in "adoption" programs, simply languished in foster care for the rest of their childhoods -- commonly in orphanages, psychiatric wards and jails -- because no one would adopt them.

And, according to critics of the system, these children commonly were unable to return to their own families because the "family-preservation" services had been "designed to fail."Under the supervision of SRS Case Managers, these services -- Family Preservation, Foster Care and Adoption -- were provided by a diverse collection of dozens of private agencies throughout the state.

These private agencies were chiefly large "charities" and small "professional" firms -- who competed to provide the various child-protection services dictated by the SRS and the courts.

The SRS Case Managers supervised the children (and sometimes their families), and oversaw the services assigned to them, supervising the private contractors' involvement with the children.

The Problem Comes to a Head:

The ACLU LawsuitThe battle began in the early 1990's, when the state's foster care system had fallen into such grotesque conditions that lawsuits were brought against the system by Rene Netherton, a guardian ad-litem (court-appointed legal guardian) for a couple of children in foster care in Northeast Kansas.

With help from the Children's Rights Project of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the lawsuits were joined into one of the first-ever "class-action" lawsuits against an entire state for operating a destructive "child-protection" system.

The lawsuit alleged that the Kansas system -- run by the SRS -- was a near-complete disaster, doing harm where it should be doing good.

It specifically charged that the SRS system violated the rights of families, conducted reckless "investigations" (or none at all), failed to provide proper family-preservation services, neglected and abused the children in foster care, sabotaged courts' and families' efforts at family-reunification, forced too many children into adoption by strangers, and bungled those adoptions.

It further alleged that the SRS put incompetent people in positions of authority, influence and power over children and families -- and failed to keep honest and reliable records of its actions.

As the years of litigation dragged on, both the state and the ACLU got tired of the fight. By now, the ACLU had spun off the Children's Rights Project as a separate organization (Children's Rights, Inc.), which went on to use its experiences with Kansas to file similar lawsuits against dozens of wretched state child-protection systems nationwide.

Meanwhile, the State of Kansas (specifically, the SRS), was facing mounting evidence of its guilt (including the murder of an infant foster child by a state-selected foster parent). Under pressure from the court, the feuding agencies agreed to settle out-of-court.

The Fragile Truce:

The Lawsuit Settlement AgreementIn the 1996 settlement agreement approved by the court, the state simply agreed to abide by its own published "standards" for the conduct of the Kansas child-protection system (commonly called the "foster care system," since foster care is typically what happens to the kids brought into the system).

The state promised to meet its own official standards for all the things it had failed to do: timely and thorough family investigations, prompt and thorough family-preservation efforts, proper care of foster children, safe and prompt adoptions for children whose parents' rights had been severed, proper training for their investigators, case managers and other staff, and honest and accurate recordkeeping.

The court needed an independent auditor to verify the SRS's compliance with its promises, and selected the Division of Legislative Post-Audit of the Kansas Legislature (commonly called the Legislative Auditor's Office). The Auditor's Office -- a fairly impartial agency, legally independent of the governor's administration -- already had considerable experience auditing other aspects of the SRS.

Over the next several years, the Auditor was to report whether the SRS met each of about eighty (80) specific criteria for proper performance. Semi-annual audits were to be issued by the Auditor's Office, showing levels of compliance.

When the SRS met the required standards for any particular criteria, in two consecutive 6-month reporting periods, then that specific criteria would be considered "fixed," and would never be checked again.

Three problems soon became evident:

To view the 15 detailed audits, as posted on the Health & Welfare Performance Audits list of the official website of the Kansas Office of Legislative Post-Audit, click here 1. DUD DATA:

... The SRS, itself, was the sole source of data for the Auditor to check -- but the SRS's recordkeeping was erratic, overdue, meaningless, inaccurate, false or simply non-existent.

(For years, Kansas had been one of the few states to never even account properly to the federal government for how it spent federal money given for child-protection. In November, 2001 (reported April 2002), an independent Legislature-funded audit, by Allen Gibbs & Houlik and Berberich Trahan & Co., indicated that over a third of SRS payments to foster care providers, made from federal funds, were improper.)

The Kansas Legislative Auditor (with a very tiny staff) ran spot-checks of the SRS foster-care system where possible, but often only enough to conclude that the SRS data was unreliable, or showed non-compliance.2. DELAYS:

... The difficulty in gathering the data made the reports very slow in coming forth. When confronted with a bad report, SRS officials would simply point out that the report was "out of date" -- claiming "we've already fixed that, now."

It would take another 6 to 12 months for a report on the current status to come out -- at which time the SRS would repeat their argument that the report was "out of date" -- repeating (as falsely as before) "we've already fixed that, now."3. DEFIANCE:

... The SRS simply stonewalled, and ignored its reform commitments almost completely. The SRS child-protection system -- even by its own criteria -- flunked audit after audit, as the system only got worse.

Yet the Childrens' Rights Project, operating on slim donations, was too-heavily embroiled in lawsuits elsewhere to be able return to Kansas and re-start its lawsuit, and the judge showed little interest in the matter.

At one point the SRS conceded it had failed to meet 80% (eighty percent) of its own criteria for the care and protection of Kansas children, and defiantly refused to offer any explanation or defense of its failure to reform -- only repeating the bureaucrat's endless complaint of too little power and money.

Yet, by this point, the SRS child-protection bureaucracy had become one of the very largest, richest and most powerful agencies of Kansas state government.Finally, as word of the flunked audits began to hit the media, and as legislators began to echo a barrage of horror stories from violated families, the judge (James Buchele) threatened in disgust to reopen the case.

A Republican governor -- Bill Graves, himself an adoptive parent -- had just been elected, and had promised to "privatize" any state office he could -- turning that state responsibility (and its state funding) over to the business community to manage. (His chief fund-raiser, Senate President Dick Bond, also headed a private foster care agency -- with eyes on control of all foster care in eastern Kansas).

Governor Graves' response to the impending legal threats against the state's child-protection system was to "privatize" it -- consolidating control of major segments of the system in the hands of a few private contractors -- something which had never been done before, anywhere.

For the new governor, Bill Graves, one of the benefits of this radical transformation of the SRS system was that the state could tell the court that it had undertaken "serious" reform -- and claim that the matter was now no longer subject to the same allocation of responsibility (and blame).

It also provided a convenient way to pay back his backer-banker / foster-care contractor Sen. Dick Bond.

Judge Buchele paused, and let the changes take shape, while the state charged wildly into the unknown.

Dodging the Issue:

"Privatization"Kansas was the first state in the history of the nation to privatize its child-protection system. Under this system, begun in the mid-1990's, certain private companies were given full charge of specific segments of the child-protection system (family preservation, foster care or adoption services) -- either state-wide (as with adoption services assigned state-wide to Lutheran Social Services) or in specific geographic areas.

Most of the initial contractors were low bidders; many were faith-based charities. Many respected long-time providers of quality child-protection services (such as The Farm, Inc.) were brushed aside, and nearly driven into bankruptcy, as their contracts were consolidated in the hands of the low bidders.

Thousands of foster children -- effectively "sold off" to the low bidders -- were uprooted from their foster homes, and moved (most against their will) to different foster homes with different foster parents, hired by the winning contractors -- or to new orphanages, psychiatric wards or other confinements. One major winning contractor, run by the governor's political ally and fundraiser, State Senate President Dick Bond, began efficiently packing foster children into a massive 6-story orphanage.

With management of most of the family preservation, foster care and adoption work turned over to private agencies, the stateís former child-protection agency (the "Children & Family Services Division" of SRS) turned its attention to expanded investigations of (and legal interventions in) Kansas families.

At the same time, on its own and without specific legislative approval, the agency broadly re-defined its own authority to intervene in families,

rejecting the tradtional "imminent risk of harm" standard, and authorizing itself to take children in any case where -- in the opinion of a single social worker -- a child faced a "likelihood of harm," someday, in that family.With about 800 social workers now re-defined as "investigators," the SRS had now become -- in effect -- the state's largest law-enforcement agency (and, in fact, repeatedly petitioned the legislature for the authority to carry guns and badges, kick down doors, and take children by force). It was far larger than the combined forces of the Kansas Bureau of Investigation, the Kansas Highway Patrol, the Capitol Police, and the investigators of the Kansas Dept. of Health and Environment -- and outnumbered the police officers of the state's largest city.

And they were operating under their own self-set standards.

The Consequences:

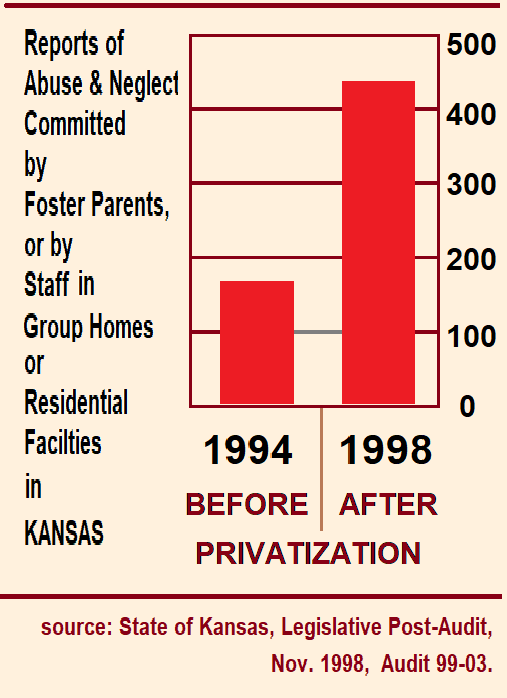

Privatization's OutcomesThe Legislatureís Auditor reported an immediate explosion in the numbers of children taken from their families and thrown into the state foster-care system -- doubling in less than a year, with a rapid increase for some time thereafter.

Since then, most of the private contractors have been swamped with more cases than ever anticipated, and fallen into grave financial trouble. Some have been driven into bankruptcy.

At the same time, the savings that were supposed to materialize have not -- replaced instead by a massive unexpected growth in state foster-care costs.

In early 2001, the Legislative Auditor's office reported:"Average program-related costs ... have increased substantially since privatization, as have State payments to help cover those costs. Overall, State funding now covers a greater portion of these agenciesí reported foster care and adoption costs."

(Source: Performance Audit Report, The Stateís Adoption and Foster Care Contracts: Reviewing Selected Financial and Service Issues, Executive Summary, with Conclusions and Recommendations, a report to the Legislative Post Audit Committee by the Legislative Division of Post Audit, State of Kansas, January 2001, 01-08, page iii, citing page 20.)

Some of the contractors who won their intital contracts with strangely low bids seemed to be confident that they would be rescued from bankruptcy by multi-million-dollar state bail-outs -- and most of them were, at first. But their slide to bankruptcy continues.

Ironically, many of the state's foster children have been taken from their homes for "neglect" -- due to nothing more than the family's abject poverty.

The grossly inefficient foster care system typically allocates somewhere between $10,000 and $20,000 per year PER CHILD.

Were that money given to the families they were taken from, and the child returned to their family, those families' "neglect" problems -- essentially defined as deprivation due to poverty -- would vanish.

But that "obvious solution" would have cost the careers of thousands of people making a living in the foster care system (backed by liberals in the legislature — and by a Governor and by Republican senators beholden to the leader of a specific foster-care contractor: Senate President Dick Bond.

[UPDATE early 2001: as of the 2000 election, the wealthy Sen.Bond retired from the legislature, following rising opposition to his conduct, but remains politically active and influential.Furthermore, transferring funding from foster care to welfare would also have violated the anti-welfare, "no-free-lunch" philosophy of many in the staunchly Republican administration and legislature.

His former right-hand man, Senator Dave Kerr, is now Senate President, and continues to thwart efforts at reform, or even critical evaluation of the privatized foster-care system

(for example, see Minutes of the Legislative Post-Audit Committee, March 19, 2003 , in which Kerr leads the opposition to a proposed audit to determine if foster children are being unfairly denied placement with close relatives, rather than foster-care contractors.)]There was (and continues to be) no powerful lobby in Topeka for Kansas children or their families -- only for the child-protection industry and for the competing political factions. Opposition to the state system from the only serious children's-interests lobbying group, Kansas Action for Children, had been neutralized by a new member of its Board of Directors -- the head of the Kaw Valley Center foster care agency, State Senate President Dick Bond.

[UPDATE, late 2002: A new industry group, "Kansas Campaign for Children," is a political-action group and lobbying organization for the private contractors who are dependent upon state funds (and state contractor payments), received for handling or holding other people's children. Senator Bond is apparently one of the group's organizers.]

Meanwhile, early audits showed that Kansas children were TWICE as likely as before (and MUCH more likely than most American children) to be taken from their homes and families.

( "Fewer foster kids are going home: Parents were less likely to regain the rights to their children in Sedgwick County, than nationwide, in 1999."

Wichita Eagle June 11, 2000

(citing James Bell & Assoc. 1999 audit for SRS),

...which notes:

"Abused or neglected children who enter foster care in [Wichita and] Sedgwick County are three times more likely than foster children across the country to never return home -- and no one can say exactly why.

"61% of all children in the county who left foster care last year were put up for adoption, compared with 30% statewide and 22% nationally,...".)Thereafter, they were routinely passed around from contractor to contractor, stranger to stranger, home to home, orphanage to orphanage -- at least yearly (but often monthly) -- by the thousands. Most effectively became homeless drifters, moved about by the state and its contractors. Of those who were forced to spend their childhoods in the Kansas system, most never finished high school.

In the ensuing years of privatization, auditors have verified the common drugging of children for contractor convenience, extensive physical injuries and widespread confinements and criminal prosecution of these foster children.

The SRS itself has conceded that a number of children have been beaten and sexually assaulted in foster care.

(for examples, see

"KANSAS FOSTER CARE: OFFICIAL FINDINGS & MEDIA REPORTS".)

In response, the troubles of these children are crudely "addressed" by ill-trained "therapists" -- usually social workers -- often operating outside their fields of expertise, or using methods not yet proven scientifically valid. Many simply torment the children with useless or counterproductive "therapies," apparently often creating problems rather than solving them.

Children mistakenly taken from healthy families have been commonly forced to "recognize" their families' "dysfunctions," and "acknowledge" their own role as a "victim." The child's eventual capitulation to this intense pressure is then used as "proof" that the family needed intervention in the first place.

Just as often, the children themselves are forced to concede shortcomings of their own -- to a "hit-and-run" therapist who forces them through emotional hoops once a week, then abandons them for the rest of the week (or month).

In fact, their therapists (and case-managers, and psychiatrists, and attorneys, and legal guardians, and even foster parents) commonly change without warning -- often monthly or more often.

These people comprise an ever-changing committee of "professionals" (called a "wrap-around team") that wraps itself around the child's life in a circle of control and manipulation -- substituting "professional expertise" for parenting.

And as soon as a child learns to please one committee, its membership changes, and the child is faced with learning how to please a different committee.

Always, the child is held accountable to the committee -- but the members of the committee have no obligation or accountability to the child.

Errors by the committee rarely bring consequences for any of its members — but always for the child.

Children who run away from this system are commonly charged as criminals when caught, including as felony "escapees." Many are routinely turned over to juvenile authorities for criminal prosecution and imprisonment.

Very many Kansas foster children are now simply dumped into the state's new "juvenile justice" system.

And federal data shows that Kansasís "protected" children are far less likely than children elsewhere in the U.S. to ever have a chance to be reunited with their families -- regardless of family efforts to meet state requirements.

Auditors (both the Legislature's Auditor and SRS's own private auditor, James Bell Associates) have shown that the state's privatized system does not deliver court-ordered family-preservation services when due -- a frequent complaint of judges, statewide.

The result is that many children are forced into adoption by strangers — under the federal government's "permanent-placement-in-18-months" rule (reduced by the Clinton administration to just 12 months) — because the state's contractors have not provided court-ordered family-preservation services to them, and their families, on time -- in time to save the families.

Epilogue:

Rhetoric, rather than ReformBoth of the stateís political parties are embarrassed by the results, but the Governor Graves and the Legislature -- those who instituted and permitted privatization -- have declined to make any measurable reforms.

Of the stateís three main private foster care contractors, the most infamous one -- Kaw Valley Center, where the courts and investigators have found extensive physical and sexual abuse of its foster children -- has been led by the Governorís leading fund-raiser, Dick Bond, a banker/politician who was President of the Kansas Senate during privatization, and who used his enormous powers to halt Legislative investigations into his own private foster care agency.

Bond has even managed to get a seat on the board of one of the two remaining major foster care contractors (KCSL), and a seat on the board of the state's ostensibly-independent "kids lobby" -- Kansas Action for Children (KAC), which subsequently has defended privatization.

Governor Graves promised substantial reform, and considerable momentum was building for it in the 1999 legislative session, following near-unanimous passage of a House bill (2571) calling for independent oversight of the SRS child-protection system. However, the bill was buried in committee by the Senate, under Senate Pres. Dick Bond, until the Governor brought all major legislation to a halt -- diverting all legislative attention to a massive and costly highway plan (Graves is heir to a major trucking firm).

SRS Secretary Rochelle Chronister was driven from office by the outrage over her handling of privatization, and her stonewalling towards the Legislature (some claimed lying) about the actions of the SRS and the outcomes of privatization.

The SRS's less-than-forthcoming manners, during legislative investigations and press inquiries, were largely credited with a groundswell of pressure from the Legislature for a more firm and explicit Open Records Act, passed in 2000, making such stonewalling a prosecutable offense. But while the Governor professed sincere backing to the inevitable bill, there have been no prosecutions yet under the bill, and SRS continues to be a challenging "source" of information for Legislative auditors, according to the most recent audit report. (click here to see the official audit summary) or click here for the Auditor's home page).

Former SRS Secretary Chronister has gone on to become a "consultant" -- advising other states on how to "achieve" what Kansas has, and has become a political player in the issue in Kansas. State Senate President Dick Bond, after his foster-care agency's grim record came to light, declined to run for re-election, but remains well-connected and active behind-the-scenes. Bond and Chronister are slated to be honored guest speakers at a "Kids Needs" conference in early 2002, hosted by industry leaders.

After half a decade of privatization -- which was supposed to resolve the stateís massive foster-care problems -- there is no end in sight. All the old problems of the system have remained (including state liability for the kids in the system), and new problems have been added.

As the numbers of children in foster care have been pared down -- largely by sending thousands to be adopted by strangers -- the Administration has declared great progress in child protection, thanks to privatization, and the governor has moved on to other issues -- picking a successor to back, and planning his pre-arranged new career as chief lobbyist for the trucking industry (President of the American Trucking Association).

Extensive pressure from the legislature, the public, and bad publicity -- and a change in leadership -- had led to a turnaround in SRS behavior by 1999-2000. The new Deputy Secretary for Children & Family Services, Joyce Allegrucci, though continuing to be foremost a defender of the bureaucracy, began a more sober and rational approach to child protection in Kansas. At least in talk and print, SRS began to reverse its emphasis on busting up families, and claimed to be prioritizing family-preservation (family-rehabilitation) programs.

But a $125 million budget shortfall in late 2001 has led the Governor to tell SRS to cut back drastically -- and SRS has primarily focused on cutting out half of its family-preservation programs, and plans to force more SRS-targeted families to pay for the costly "services" imposed on them by the child-protection system -- including foster care for their children.

[UPDATE, early 2003: The departing Graves Administration and Legislature left the incoming Administration and Legislature facing a massive budget deficit, forbidden by the state constitution. New governor is Kathleen Sebelius, and Joyce Allegrucci (previously head of the SRS child-protection system) was her Campaign Manager, then Transition Team Manager. Both Administrations have sought to cut costs by chopping funding in half for family-preservation services -- while maintaining full funding for the far-more-expensive business of foster care.][UPDATE, mid-2004: Allegrucci is now the Governorís Chief of Staff, manager of the governor's office, and the second most powerful person in the administration, after the governor herself. (Also, Allegrucci's husband, Donald, is now Chief Justice of the Kansas Supreme Court.)]

Last year, the new SRS Deputy Secretary for Children & Family Services admitted in a Legislative hearing that over 1,000 children now in foster care should never have been taken by the state, and a later SRS press release admitted 1,800 Kansas foster children belonged at home, instead. Critics charge that the number is much higher.

Currently, in 2001, over 4,000 Kansas children are in the hands of the state's private contractors

[UPDATE, mid-2004: now over 6,000 Kansas children].

But no one (not even the SRS) knows the exact number of children in Kansas foster care -- nor where, exactly, they all are.

~Richard Harris

former Commissioner,

Civil Rights / EEO Commission,

City of Wichita, Kansas

October 2001

Partially updated and revised, July 30, 2004

COMING SOON: Links to other sources.

Click here to return to the menu of this KANSAS Special Information Section

Click here to return to the CHILD PROTECTION DEMONSTRATION WEBSITE GATEWAY