Return to Aviation Answer-Man Gateway

Return to Cessna History Timeline

Return to Cessna History Timeline

Cessna: The Early Years

In 1911, although the "aeroplane" was more an exciting gimmick than a practical invention, there had emerged an outstanding plane, the French Bleriot Model XI, a small, delicate monoplane (one wing, compared to twin-wing biplanes) with good performance and handling, on a small, efficient engine and inexpensive airframe. (see "Eight Great Airplanes," Chapter 2: The Bleriot Model XI, on this website).

At the end of the Oklahoma City show, as the monoplane was being disassembled for shipment, Clyde Cessna carefully watched -- and memorized every detail he could. Afterwards, everything he could remember about the monoplane was noted or drawn on paper. He then took a long trip to New York City, where the Queens Aeroplane Company was building copies of the Bleriot. To learn as much as he could about the plane, he spent a month working in the Queens factory.

Clyde then bought a Queens Monoplane fuselage that had been meant for an another customer who was killed in a crash before he could collect it (ironically, the unlucky Queens customer was John B. Moisant, whose aerial exhibition team had first fascinated Cessna in Oklahoma). Taking the late Moisant's monoplane fuselage home to Oklahoma, Cessna modified a 60-horsepower boat engine to power it, and built the rest of the plane himself -- including the critical structures of wings and tail.

In the process, Clyde Cessna became the first person in the vast American heartland -- between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains -- to build and fly an airplane.

But he was nearly bankrupted by his flying exploits, and retreated to his family's land in rural Kansas, where Clyde owned 40 acres and a barn -- into which he moved his family... and his airplane-building.

In 1915, Cessna performed in Wichita, Kansas -- the large city nearest to his hometown -- becoming the first to fly a monoplane there. Little did he know that this city would soon transform his life -- for better and worse -- and make his name famous among aviators worldwide.

The following year, in 1916, Cessna was invited by his former car-sales boss, J.J. Jones -- now a Wichita auto manufacturer -- to build airplanes in part of the Wichita car factory, with use of the factory's sophisticated manufacturing machinery. Jones wanted the publicity that Cessna's remarkable flying machines would bring to his Jones Car Company and its automobiles.

[NOTE: This was to be a transforming moment for Wichita, which would gradually grow its airplane-manufacturing industry until it became the birthplace of more airplanes than any other city on Earth, eventually becoming the "Air Capital of the World."]

Overseas, the First World War, (which had been raging in Europe since 1914), finally drew in the United States. All flying exhibitions were canceled, as America's attention turned to more serious matters. Cessna returned to his Kansas farm, and farmed his way through the war.

From 1917 until 1925, Clyde Cessna stayed in rural work, but watched the developments in aviation -- and in Wichita, where other aviators were starting their own aircraft-building enterprises. Famous early American "barnstorming" (exhibition) aviator "Matty" Laird, while flying in Wichita, had met and teamed-up with Wichita oil-magnate Jake Mollendick to start America's first commercial airplane-manufacturing company: E.M.Laird Aviation. (soon renamed Swallow Airplane Mfg. Co.). The graceful, efficient, speedy Swallow biplanes were fast, and their race-winning speed kept them in high demand, nationwide.

But Clyde Cessna had begun his aviation career in his Bleriot-style Silverwings monoplane, and was acutely tuned to the monoplane's advantages: less construction work and fewer materials to build, lighter weight and better pilot visibility (in some cases), and -- most of all -- less drag.

Without the complex framework of wires and struts joining the two wings and holding them in place, the monoplane had less drag-producing hardware hanging out in the breeze -- reducing drag, and increasing speed. Another source of drag the biplane suffered greatly from was the wasted lift and increased drag caused by the tendency of high-pressure air slipping out from under each wing, sideways, and spiraling off the wingtip to produce tiny, horizontal tornadoes trailing behind each the wingtip, dragging on the airplane. This "induced drag" was reduced in monoplanes, which which had half as many wingtips to produce drag -- their one, long "monoplane" wing being more efficient than a pair of short "biplane" wings.

With the reduction in drag and weight, the monoplane could get by with a smaller, less-expensive engine (the most expensive part of the airplane).

But, at first, Cessna's idea of a cantiliever monoplane was considered unreasonable by most, and his friends pleaded with him to abandon this idea, which would surely get him killed. They thought it was dangerous -- even suicidal -- to elminate the external bracing struts that had provided critical strength to virtually all monoplanes but Fokker's -- including all Travel Air monoplanes and the "Sprit of St.Louis." To make up for the absence of struts, they believed, the wing would have to have main beams ("spars") so thick and heavy as to make the plane impractical, or unflyable.

But Cessna was determined, and quicky produced an enclosed-cabin plane,with a thick-but-strutless wing -- one of the first in America. With a stout engine, and seats for four people, the plane was speedy. Cessna gave it the name "Comet" (from his earlier record-setting Bleriot-style monoplane. Sure that the idea was viable, and sellable, Cessna worked on an improved model, with cleaner lines, bigger windows for the passengers, and other improvements. The resulting plane won race after race -- against airplanes with much more horsepower. The clean Cessna cantilever wing began proving its superiority, and becoming famous.

The plane was designed to be available with a wide assortment of engines. The most popular Cessna "A" Model turned out to be the Cessna "AW" (shown here) -- a Cessna "A" Model with a 110-125 horsepower Warner "Scarab" radial engine (the only American-made engine Cessna offered).

In September of 1928, Cessna test pilot Earl Rowland brought the Cessna AW to national fame, using it to win the Class A Transcontinental Air Derby, and following up with the 50-mile-race trophy at the National Air Races. The Cessna's clean, cantilever wing was clearly an advantage, and the Cessna name suddenly became a national hallmark of performance.

But the wrangling with the government -- and Cessna's own operational problems -- had cost him nearly a year. In the meantime, the company had run up enormous debts, as it built factories and planes (in response to the growing number of orders) without any actual aircraft sales (for lack of government approval).

By 1928, though, the performance of Cessna airplanes in major air races had made the sleek, speedy Cessna design an object of desire among many prospective airplane buyers. The Curtiss Flying Service -- a major aviation training service, with access to many prospective airplane buyers -- offered to become the exclusive distributor for Cessna planes, claiming it could sell up to 50 a month, if Cessna would expand its manufacturing capacity to be able to deliver such a high volume of aircraft.

So Clyde Cessna -- like so many entrepreneurs of the late 1920's -- began selling stock to the wildly optimistic investors of the "Roaring '20's." In the process, Clyde slowly lost the majority ownership of the company. Though he remained its largest shareholder, and President, he no longer had the necessary 51%-share ownership to be sure of staying in control.

Then everything began to fall apart. In the very late 1920's, the fragile world-wide economic "house of cards" that had been built by recklessly optimistic investors, and poor management of their investments, suddenly began to tremble, then tumble -- as stockholders began to realize that many of their companies had wasted their investment money. Investors worldwide began to sell off their stock (most of it bought on credit) in a panic. As their stock flooded the market, stock prices plummeted.

With the world's wealthy suddenly bankrupted, the demand for expensive, exotic items -- including airplanes -- suddenly evaporated. The Curtiss Flying Service, which had pushed Cessna into gambling on a huge new factory, was suddenly bankrupt and gone -- leaving Cessna Aircraft Company with its expensive new factory, its massive debt, and no market for its airplanes. At the annual stockholders' meeting in February, 1930, a pall of defeat hung over the proceedings.

But Cessna, once a very successful car salesman, talked them into believing that some planes could still be sold. There were still a few people out there with plenty of money, he assured them, and added that he'd been working on another project, as well.

Despite the Depression, the flying bug had spread to people not wealthy enough to engage in powered flight, and they had found an outlet through local "glider clubs," where small, primitive gliders (like the one below, left, gliding into a landing) could be launched into the air from hillsides or by being dragged up to flying speed behind automobiles or airplanes. With his son, Eldon, Clyde Cessna had developed a simple, lightweight, single-seat glider -- the CG-2 (right, and below, left) -- to sell to glider clubs. And they were selling (though at only $400 each, compared to the much-more-profitable powered Cessna airplanes).

At the same time, ownership of whole companies had changed hands multiple times in the panic selling. With the changing of stockholders, Clyde Cessna soon found himself facing a new Board of Directors, who voted him out the door, and closed down the Cessna factory, to await better times. In the meantime, the investors kept the company alive on paper, and paid on its debts, by renting out the Cessna factory buildings to other comnpanies.

Clyde Cessna was devastated, and returned in grief to his farm, where he stayed for the next 5 years.

This paradox was too extreme to last.

[KEEP WATCH HERE FOR MORE !!! ~ R.Harris]

Return to Aviation Answer-Man Gateway

Copyright 2002 by Richard Harris

All Rights Reserved

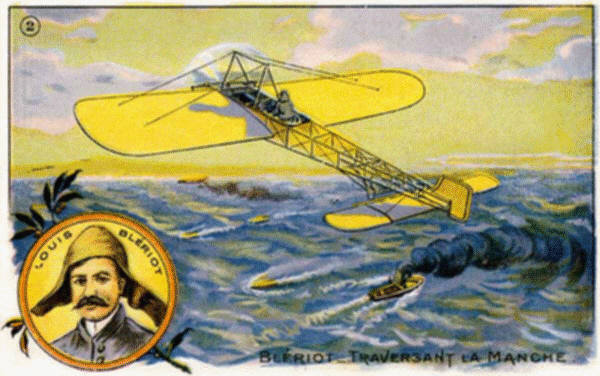

Louis Bleriot had made his monoplane famous in 1909, by flying across the English Channel, from France to Britain -- becoming the first person ever to successfully fly across open sea, and from one country to another. The achievement shook the world, and made the airplane finally seem powerful, capable and important. The Bleriot design -- far simpler and more practical than most contemporary designs (such as the slow, awkward Wright Flyer) -- became wildly popular, and aviators all over the world rushed to acquire a Bleriot-style monoplane of their own.

Louis Bleriot had made his monoplane famous in 1909, by flying across the English Channel, from France to Britain -- becoming the first person ever to successfully fly across open sea, and from one country to another. The achievement shook the world, and made the airplane finally seem powerful, capable and important. The Bleriot design -- far simpler and more practical than most contemporary designs (such as the slow, awkward Wright Flyer) -- became wildly popular, and aviators all over the world rushed to acquire a Bleriot-style monoplane of their own.

Among them was a 30-year-old Clyde Cessna -- an Enid, Oklahoma farmer, car salesman and mechanical handyman. Cessna first saw airplanes at a exhibition of flying machines in Oklahoma City, in Febrauary, 1911. He was fascinated. And when he learned that one of the pilots was collecting $10,000 for a three-minute flight, he was sure he could do it, too. One of the planes was a Bleriot monoplane, flown by a Frenchman, and Cessna examined it at every chance. He immediately decided to build a flying machine of his own -- by copying the Bleriot.

Among them was a 30-year-old Clyde Cessna -- an Enid, Oklahoma farmer, car salesman and mechanical handyman. Cessna first saw airplanes at a exhibition of flying machines in Oklahoma City, in Febrauary, 1911. He was fascinated. And when he learned that one of the pilots was collecting $10,000 for a three-minute flight, he was sure he could do it, too. One of the planes was a Bleriot monoplane, flown by a Frenchman, and Cessna examined it at every chance. He immediately decided to build a flying machine of his own -- by copying the Bleriot.

After much labor, using the finest materials he could buy, and the craftsmanship for which he was known, Cessna's first plane was ready. To crash. Which it did -- a dozen times in a row. After many rebuilds, and weeks in the hospital, the determined Cessna finally got his monoplane off the ground, and -- through repeated crashes (like Bleriot before him) and constant public ridicule -- Clyde taught himself to fly the thing.

After much labor, using the finest materials he could buy, and the craftsmanship for which he was known, Cessna's first plane was ready. To crash. Which it did -- a dozen times in a row. After many rebuilds, and weeks in the hospital, the determined Cessna finally got his monoplane off the ground, and -- through repeated crashes (like Bleriot before him) and constant public ridicule -- Clyde taught himself to fly the thing.

In 1911, flying machines were an extraordinary sight anywhere in America, but especially so in the remote rural communities and small cities of America's heartland. Cessna named the plane "Silverwings", and parlayed his extraordinary posession into a profitable road show, flying at exhibtions around the American midwest, thrilling crowds with daring stunts, and involving them with his trademark football throw (the person on the ground below who caught it won a prize). Every year, during the winter, Clyde built another plane for exhibtion during the summer. Each year's monoplane was a slightly improved version of the one before.

In 1911, flying machines were an extraordinary sight anywhere in America, but especially so in the remote rural communities and small cities of America's heartland. Cessna named the plane "Silverwings", and parlayed his extraordinary posession into a profitable road show, flying at exhibtions around the American midwest, thrilling crowds with daring stunts, and involving them with his trademark football throw (the person on the ground below who caught it won a prize). Every year, during the winter, Clyde built another plane for exhibtion during the summer. Each year's monoplane was a slightly improved version of the one before.

The discovery of oil just east of Wichita had made it a boom town, and there was money to be made, and plenty of well-off people ready to spend it. A budding businessman could hardly resist. And the Jones car factory was better-equipped than his rural barn. Cessna agreed, and began painting the "Jones" name on the wing of his new show planes.

The discovery of oil just east of Wichita had made it a boom town, and there was money to be made, and plenty of well-off people ready to spend it. A budding businessman could hardly resist. And the Jones car factory was better-equipped than his rural barn. Cessna agreed, and began painting the "Jones" name on the wing of his new show planes.

In the winter of 1916-1917, Cessna focused on building planes for himself, to perform in. He built a remarkably-streamlined, completely-enclosed monoplane, naming it "the Comet," with which he promptly set an astounding national speed record of 124mph, covering the 76 miles from Blackwell, Oklahoma to Wichita, Kansas in just 36 minutes (though probably helped by the strong southerly winds of that area).

In the winter of 1916-1917, Cessna focused on building planes for himself, to perform in. He built a remarkably-streamlined, completely-enclosed monoplane, naming it "the Comet," with which he promptly set an astounding national speed record of 124mph, covering the 76 miles from Blackwell, Oklahoma to Wichita, Kansas in just 36 minutes (though probably helped by the strong southerly winds of that area).

Travel Air years: 1926-1927

Among Swallow Airplane's employees were Walter Beech (left) and Lloyd Stearman (below,right). Beech -- an Army pilot during World War I -- had seen the War's rapid change in the design of military airplane frames, from fragile wood to sturdy metal. Beech and Stearman felt strongly that the Swallow should incorporate the latest design innovations -- particularly all-metal frames.

Among Swallow Airplane's employees were Walter Beech (left) and Lloyd Stearman (below,right). Beech -- an Army pilot during World War I -- had seen the War's rapid change in the design of military airplane frames, from fragile wood to sturdy metal. Beech and Stearman felt strongly that the Swallow should incorporate the latest design innovations -- particularly all-metal frames.

The Swallow Airplane's management did not agree, so Beech and Stearman joined forces to strike out on their own, and create a new airplane manufacturing company -- Travel Air Mfg. Co., across town. They invited Clyde Cessna -- who had a little money, and clearly had the knack of building airplanes and showing them off -- to join them as President of Travel Air. Cessna accepted, and the trio began to build what would quickly become the pre-eminent light-plane maker in America.

The Swallow Airplane's management did not agree, so Beech and Stearman joined forces to strike out on their own, and create a new airplane manufacturing company -- Travel Air Mfg. Co., across town. They invited Clyde Cessna -- who had a little money, and clearly had the knack of building airplanes and showing them off -- to join them as President of Travel Air. Cessna accepted, and the trio began to build what would quickly become the pre-eminent light-plane maker in America.

The sturdy construction of Travel Air biplanes (like the Model 2000, left), their streamlining and their powerful, high-quality engines, made them outstanding aircraft. While other biplanes did well to hoist two people, the Travel Air biplanes were able to hoist three -- and fly faster than almost any competing aircraft. They became coveted and prized posessions of the wealthy and aviation-obsessed. Barnstormers cherished them as real money-makers (they could carry two paying passengers rather than just one), and business flyers (a rare breed, in those days) saw them as powerful business tools in the race of competitive commerce. Travel Airs were bought by the hundreds. By 1929, half of the light airplanes made in America would be Travel Airs.

The sturdy construction of Travel Air biplanes (like the Model 2000, left), their streamlining and their powerful, high-quality engines, made them outstanding aircraft. While other biplanes did well to hoist two people, the Travel Air biplanes were able to hoist three -- and fly faster than almost any competing aircraft. They became coveted and prized posessions of the wealthy and aviation-obsessed. Barnstormers cherished them as real money-makers (they could carry two paying passengers rather than just one), and business flyers (a rare breed, in those days) saw them as powerful business tools in the race of competitive commerce. Travel Airs were bought by the hundreds. By 1929, half of the light airplanes made in America would be Travel Airs.

But Clyde Cessna became soon disenchanted with life at Travel Air. The first major difference with Walter Beech, the company's top executive, was over over which type of plane to build: BI-planes (two wings, one above the other) or MONO-planes (just one wing). Up to this time, biplanes were widely preferred, because it was easier to build them strongly. The two wings could be mutually reinforced by a complex web of struts and wires between them. With the poor quality of materials in the 1920's, and the relatively primitive state of airplane technology, the safety afforded by biplanes was generally preferred. And by using two wings, each wing could be kept fairly short, eliminating the need for big, strong beams (called "spars") running the length of the wing; ordinary, lightweight wing spars were sufficient. Also, if stretched, the biplane's extra wing could greatly increase the load that could be carried -- including the size of engine that could be used.

But Clyde Cessna became soon disenchanted with life at Travel Air. The first major difference with Walter Beech, the company's top executive, was over over which type of plane to build: BI-planes (two wings, one above the other) or MONO-planes (just one wing). Up to this time, biplanes were widely preferred, because it was easier to build them strongly. The two wings could be mutually reinforced by a complex web of struts and wires between them. With the poor quality of materials in the 1920's, and the relatively primitive state of airplane technology, the safety afforded by biplanes was generally preferred. And by using two wings, each wing could be kept fairly short, eliminating the need for big, strong beams (called "spars") running the length of the wing; ordinary, lightweight wing spars were sufficient. Also, if stretched, the biplane's extra wing could greatly increase the load that could be carried -- including the size of engine that could be used.

After working days at his Travel Air job, Cessna went to a shop of his own, across the river, and began building a monoplane. Braced only by a few slender struts, the high-wing design proved to be efficient and speedy. When finished, and tested, Cessna showed it to Walter Beech, who was surprised by its virtues, and allowed Cessna to manufacture a modified version at Travel Air, as the Travel Air 5000. Several of the roomy, comfortable enclosed-cabin monoplanes were used in record-setting, long-distance flights. National Air Transport, America's first major airline, was impressed. NAT bought several and used them extensively for mail, cargo and passenger service.

After working days at his Travel Air job, Cessna went to a shop of his own, across the river, and began building a monoplane. Braced only by a few slender struts, the high-wing design proved to be efficient and speedy. When finished, and tested, Cessna showed it to Walter Beech, who was surprised by its virtues, and allowed Cessna to manufacture a modified version at Travel Air, as the Travel Air 5000. Several of the roomy, comfortable enclosed-cabin monoplanes were used in record-setting, long-distance flights. National Air Transport, America's first major airline, was impressed. NAT bought several and used them extensively for mail, cargo and passenger service.

But most of Travel Air's business was still in building traditional biplanes. And when Cessna brought up the idea of building monoplanes with no external bracing (to reduce drag) the idea couldn't get past Walter Beech, the biplane builder. The concept of the "cantilever" monoplane (below, right) was radical. Only a Dutch plane-builder, Anthony Fokker, had had any success with the idea. Walter Beech put his foot down, and said "no." In 1927, Clyde Cessna -- obsessed with taking monoplane design to perfection -- sold his Travel Air stock to Walter Beech, then resigned from Travel Air, and started his own company across the river.

But most of Travel Air's business was still in building traditional biplanes. And when Cessna brought up the idea of building monoplanes with no external bracing (to reduce drag) the idea couldn't get past Walter Beech, the biplane builder. The concept of the "cantilever" monoplane (below, right) was radical. Only a Dutch plane-builder, Anthony Fokker, had had any success with the idea. Walter Beech put his foot down, and said "no." In 1927, Clyde Cessna -- obsessed with taking monoplane design to perfection -- sold his Travel Air stock to Walter Beech, then resigned from Travel Air, and started his own company across the river.

1927-1929:

Cessna Aircraft Company begins

It was April of 1927. A prize had been offered for the first non-stop flight between New York and Paris, across the icy North Atlantic. After several biplanes had failed to directly cross the Atlantic Ocean (or disappeared over it), a bold, lone pilot in a single-engine Ryan monoplane succeeded, and the world went wild over his daring success. The "Lone Eagle" was Charles Lindbergh (left). And Lindberghs' sturdy, efficient, ocean-spanning Ryan "NYP" (New York-to-Paris) monoplane -- the "Sprit of St.Louis" (left and right) -- made the biplane seem obsolete overnight. Clyde Cessna's basic belief in monoplanes was vindicated.

It was April of 1927. A prize had been offered for the first non-stop flight between New York and Paris, across the icy North Atlantic. After several biplanes had failed to directly cross the Atlantic Ocean (or disappeared over it), a bold, lone pilot in a single-engine Ryan monoplane succeeded, and the world went wild over his daring success. The "Lone Eagle" was Charles Lindbergh (left). And Lindberghs' sturdy, efficient, ocean-spanning Ryan "NYP" (New York-to-Paris) monoplane -- the "Sprit of St.Louis" (left and right) -- made the biplane seem obsolete overnight. Clyde Cessna's basic belief in monoplanes was vindicated.

Clyde was ready to put the Cessna design on the market, and in early 1928, development efforts of the Cessna company were turned to getting government approval ("certification") for a basic, 4-seat version of the cantilever plane, which Cessna could manufacture and sell commercially. Thus was born the sleek, clean, fast Cessna "A" Model (right). A leap ahead in airplane efficiency, it was an attention-grabber. On only 110 horsepower, the Cessna Model A could cruise at 110mph for 650 miles -- a stunning acheivement in speed and efficiency for the times (and definitely respectable even by today's standards).

Clyde was ready to put the Cessna design on the market, and in early 1928, development efforts of the Cessna company were turned to getting government approval ("certification") for a basic, 4-seat version of the cantilever plane, which Cessna could manufacture and sell commercially. Thus was born the sleek, clean, fast Cessna "A" Model (right). A leap ahead in airplane efficiency, it was an attention-grabber. On only 110 horsepower, the Cessna Model A could cruise at 110mph for 650 miles -- a stunning acheivement in speed and efficiency for the times (and definitely respectable even by today's standards).

The cantilever wing, however, caused skeptical government regulators to balk. Cessna had to perform all kinds of extraordinary demonstrations of the wing's strength to persuade government officals that the plane was safe. His most famous act was to have 17 men standing on the wing of a Cessna plane -- spread out across its entire span. A photo of that stunt (left) would become standard Cessna sales material for years.

The cantilever wing, however, caused skeptical government regulators to balk. Cessna had to perform all kinds of extraordinary demonstrations of the wing's strength to persuade government officals that the plane was safe. His most famous act was to have 17 men standing on the wing of a Cessna plane -- spread out across its entire span. A photo of that stunt (left) would become standard Cessna sales material for years.

Manufacturing expansion is very expensive. Land and buildings must be acquired. Then machinery, tooling and materials must be gathered in the buildings to make a factory. Then a workforce must be hired and trained. Normally, when building airplanes, little or no money is received until after the finished product is rolled out the door -- but the expenses for making the plane (labor, materials and other expenses) must be paid for promptly. A huge pile of money must be acquired and spent by the company before the planes are built and sold -- or they never will be.

Manufacturing expansion is very expensive. Land and buildings must be acquired. Then machinery, tooling and materials must be gathered in the buildings to make a factory. Then a workforce must be hired and trained. Normally, when building airplanes, little or no money is received until after the finished product is rolled out the door -- but the expenses for making the plane (labor, materials and other expenses) must be paid for promptly. A huge pile of money must be acquired and spent by the company before the planes are built and sold -- or they never will be.

With the resulting influx of cash, the company rapidly began building a large factory complex next to Wichta's first municipal airport, southeast of town. (Lloyd Stearman, his former colleague from Travel Air, had already begun manufcturing Stearman biplanes there. Boeing would later take over the Stearman plant, and the airport would become McConnell Air Force Base, but the Cessna factory remains today.) Cessna -- after sacrificing controlling interest in his company -- now had the makings of becoming a major airplane manufacturer -- the equal of his old colleague Walter Beech.

With the resulting influx of cash, the company rapidly began building a large factory complex next to Wichta's first municipal airport, southeast of town. (Lloyd Stearman, his former colleague from Travel Air, had already begun manufcturing Stearman biplanes there. Boeing would later take over the Stearman plant, and the airport would become McConnell Air Force Base, but the Cessna factory remains today.) Cessna -- after sacrificing controlling interest in his company -- now had the makings of becoming a major airplane manufacturer -- the equal of his old colleague Walter Beech.

1929-1931: The Great Depression Clobbers Everyone

When the panic peaked in U.S. stock markets, October 29, 1929, the bottom completely dropped out of the stock market. Hundreds of thousands of investors lost virtually everything they had invested. Banks across the industrial world, which had carelessly loaned money to reckless investors, were suddenly faced with unrecoverable losses, and began going bankrupt, themselves. The economy of the entire industrialized world began to stagger and falter into the greatest economic depression of the 20th Century: the Great Depression.

When the panic peaked in U.S. stock markets, October 29, 1929, the bottom completely dropped out of the stock market. Hundreds of thousands of investors lost virtually everything they had invested. Banks across the industrial world, which had carelessly loaned money to reckless investors, were suddenly faced with unrecoverable losses, and began going bankrupt, themselves. The economy of the entire industrialized world began to stagger and falter into the greatest economic depression of the 20th Century: the Great Depression.

With Clyde Cessna's optimistic arm-twisting, the Board of Directors reluctantly held its breath, and gave Cessna the go-ahead to continue production. For the rest of 1930, Cessna Aircraft Company (unlike most other airplane companies) stayed in business. The company managed to sell a few of the Cessna "A" models, (particularly the "AW"), and about 300 of its cheap, dainty (and dangerous) CG-2 gliders. But Cessna's aircraft were either too big-and-expensive to sell, or too small-and-cheap to generate substantial sales income -- and the father-and-son Cessnas continued to search for a better product.

With Clyde Cessna's optimistic arm-twisting, the Board of Directors reluctantly held its breath, and gave Cessna the go-ahead to continue production. For the rest of 1930, Cessna Aircraft Company (unlike most other airplane companies) stayed in business. The company managed to sell a few of the Cessna "A" models, (particularly the "AW"), and about 300 of its cheap, dainty (and dangerous) CG-2 gliders. But Cessna's aircraft were either too big-and-expensive to sell, or too small-and-cheap to generate substantial sales income -- and the father-and-son Cessnas continued to search for a better product.

Clyde's son, Eldon, went to work trying to develop a cheap, tiny, powered plane that might be saleable in the tight aviation market. Eldon's "EC-2 Baby Cessna" was the result (left). But it was too little, too late. Cessna had been beaten to the market by the Piper J-3 Cub (right) -- the beginning of a long and intense rivalry between a pair of companies which would (in time) become the world's two leading producers of light planes.

Clyde's son, Eldon, went to work trying to develop a cheap, tiny, powered plane that might be saleable in the tight aviation market. Eldon's "EC-2 Baby Cessna" was the result (left). But it was too little, too late. Cessna had been beaten to the market by the Piper J-3 Cub (right) -- the beginning of a long and intense rivalry between a pair of companies which would (in time) become the world's two leading producers of light planes.

About the same time, Walter Beech's Travel Air -- now in a large factory on the eastern outskirts of Wichita -- was facing hard times. By the end of 1929, Walter Beech had sold out his interest in the company to his greatest creditor: Curtiss-Wright Corporation (who supplied the Travel Air's engine -- its most expensive part). The Travel Air Company, like Cessna Aircraft Company, was closed down. Walter Beech went back East to work for Curtiss-Wright as Vice President of Sales, but -- by 1932 -- he returned to Wichita with his wife Olive Ann -- determined to rebuild his own airplane company from the ashes of Travel Air.

About the same time, Walter Beech's Travel Air -- now in a large factory on the eastern outskirts of Wichita -- was facing hard times. By the end of 1929, Walter Beech had sold out his interest in the company to his greatest creditor: Curtiss-Wright Corporation (who supplied the Travel Air's engine -- its most expensive part). The Travel Air Company, like Cessna Aircraft Company, was closed down. Walter Beech went back East to work for Curtiss-Wright as Vice President of Sales, but -- by 1932 -- he returned to Wichita with his wife Olive Ann -- determined to rebuild his own airplane company from the ashes of Travel Air.

At first, though, Beech (left, shorter man) had no place to start building a prototype plane, which he would need to have to attract investors. He wound up renting space in the abandoned Cessna factory for a while. And among the first Wichitans to go to work for him was a young graduate of Wichita University's newly-developed "aeronautical engineering" program, named Dwayne Wallace (left, taller man).

At first, though, Beech (left, shorter man) had no place to start building a prototype plane, which he would need to have to attract investors. He wound up renting space in the abandoned Cessna factory for a while. And among the first Wichitans to go to work for him was a young graduate of Wichita University's newly-developed "aeronautical engineering" program, named Dwayne Wallace (left, taller man).

When young Wallace had entered the "AE" program at Wichita U., he had actually expected that he would eventually go to work for Clyde Cessna -- his uncle. But, for now, just about the only employer in town needing an aeronautical engineer was Walter Beech. So Clyde Cessna's nephew began working in the fairly new Cessna factory, helping his uncle's biggest competitor create the first "Beechcraft."

When young Wallace had entered the "AE" program at Wichita U., he had actually expected that he would eventually go to work for Clyde Cessna -- his uncle. But, for now, just about the only employer in town needing an aeronautical engineer was Walter Beech. So Clyde Cessna's nephew began working in the fairly new Cessna factory, helping his uncle's biggest competitor create the first "Beechcraft."

Eventually, . . .

Return to Cessna History Timeline

Return to Cessna History Timeline