Return to

Return toAviation Answer-Man

Gateway

Return to

Return to

Aviation Answer-Man

Gateway

Return to

Return toThe Aero Commander Line

~~~~~~~~~~~

A short history

Copyright 2000, 2001 by Richard Harris

All Rights

Reserved

Revised September 2001

In the late 1940's / early

1950's, aeronautical engineer Ted Smith designed the first Aero Commander twin, the Model 520 -- which would become the forerunner of a long line of respected medium-sized, twin-engine private aircraft. The first prototype flew on April 27, 1948, and the first production Model 520 came out of the Bethany, Oklahoma factory in August of 1951. Using using modern, slim, "flat-six" piston engines, and modern, lightweight, sheet-metal hollow-shell ("semi-monocoque") construction, Smith's Model 520 was the first true, modern "light twin" on the market.

In the late 1940's / early

1950's, aeronautical engineer Ted Smith designed the first Aero Commander twin, the Model 520 -- which would become the forerunner of a long line of respected medium-sized, twin-engine private aircraft. The first prototype flew on April 27, 1948, and the first production Model 520 came out of the Bethany, Oklahoma factory in August of 1951. Using using modern, slim, "flat-six" piston engines, and modern, lightweight, sheet-metal hollow-shell ("semi-monocoque") construction, Smith's Model 520 was the first true, modern "light twin" on the market.

The 520 bore

more than a passing resemblance to the Douglas A-26 Invader -- a World-War-II attack bomber (shown at left) which Ted Smith had helped design. With its high wings (45 feet long), and a 7-foot-tall tail, the spacious Aero Commander 520 (1952 model shown at top, right) was a remarkably grand airplane for a "light twin." It had lots of interior room, and considerable load capacity, easily seating 5, and able to squeeze in two more in optional rear-facing seats

squeezed between the front and back seats. Powered by a pair of 240-horsepower, geared "flat-six" piston engines, the 520 could cruise along at about 200 miles per hour -- in a day when many airliners were still only flying at 180 miles per hour.

The 520 bore

more than a passing resemblance to the Douglas A-26 Invader -- a World-War-II attack bomber (shown at left) which Ted Smith had helped design. With its high wings (45 feet long), and a 7-foot-tall tail, the spacious Aero Commander 520 (1952 model shown at top, right) was a remarkably grand airplane for a "light twin." It had lots of interior room, and considerable load capacity, easily seating 5, and able to squeeze in two more in optional rear-facing seats

squeezed between the front and back seats. Powered by a pair of 240-horsepower, geared "flat-six" piston engines, the 520 could cruise along at about 200 miles per hour -- in a day when many airliners were still only flying at 180 miles per hour.

In the early 1950's, World-War-II vintage, war-surplus military transports and light bombers had flooded the civilian market, being converted to carry passengers or serve as executive transports. They were generally either fast or capable of great loads, or both. But most were tugged along by antiquated, massive, roaring, fuel-hungry, oil-burning radial engines (shown at right). In general, the war-surplus, twin-engine planes, themselves, were heavy, gas-guzzling, noisy, war-worn beasts, and not well-suited to efficient-and-comfortable flying for personal or business use. Both inelegant and impractical, they lacked the finesse of a truly personal plane.

At the time, the only currently-manufactured civilian twin competing with the Aero Commander Model 520 was the the 15-year-old Beechcraft Model 18 "Twin Beech" which -- though powerful, fast and roomier than the Model 520 -- was still powered by noisy, thirsty, 1930's-vintage radial engines, and was supported on awkward, obsolete, "tail-dragging" landing gear (two main wheels and a tailwheel). These features, added to its great bulk and crude aerodynamics, meant that the Twin Beech was not nearly as graceful,

efficent, gentle, or well-mannered craft as the Aero Commander Model 520.

At the time, the only currently-manufactured civilian twin competing with the Aero Commander Model 520 was the the 15-year-old Beechcraft Model 18 "Twin Beech" which -- though powerful, fast and roomier than the Model 520 -- was still powered by noisy, thirsty, 1930's-vintage radial engines, and was supported on awkward, obsolete, "tail-dragging" landing gear (two main wheels and a tailwheel). These features, added to its great bulk and crude aerodynamics, meant that the Twin Beech was not nearly as graceful,

efficent, gentle, or well-mannered craft as the Aero Commander Model 520.

And so the first Aero Commander was -- at first -- in a class by itself.

It was soon joined in the market by the Beechcraft Model 50 Twin Bonanza (only loosely related to the popular Beech Bonanza) -- a low-winged modern medium twin with performance and cabin space comparable to the Model 520. But the Aero Commander, with a slight edge in efficiency and capacity, and better flying characteristics, remained the better buy. Hundreds were sold over the next few years.

Despite the grand aura of a private airliner, the Model 520 was blessed with superb handling characteristics, great visibility, an easy-to-manage cockpit, and good short-field / rough-field capability (important in an age when most airfields were still crude, unpaved landing strips). To demonstrate its great resistance to engine-out handling problems (which plagued light twins of the day), a propellor was removed from the "critical" engine of the first prototype

-- which was then flown, non-stop, from Oklahoma to Washington, D.C. This successful stunt would serve as a valuable lesson for a company that would eventually benefit considerably from "stunt marketing," thanks to an extraordinary aviatrix,

Jerrie Cobb

and a high-flying company vice-president named Bob Hoover (see below).

Despite the grand aura of a private airliner, the Model 520 was blessed with superb handling characteristics, great visibility, an easy-to-manage cockpit, and good short-field / rough-field capability (important in an age when most airfields were still crude, unpaved landing strips). To demonstrate its great resistance to engine-out handling problems (which plagued light twins of the day), a propellor was removed from the "critical" engine of the first prototype

-- which was then flown, non-stop, from Oklahoma to Washington, D.C. This successful stunt would serve as a valuable lesson for a company that would eventually benefit considerably from "stunt marketing," thanks to an extraordinary aviatrix,

Jerrie Cobb

and a high-flying company vice-president named Bob Hoover (see below).

To manufacture his design, Smith had created a company called Aero Design and Engineering, in Bethany, Oklahoma -- a suburb of Oklahoma City. The company quickly became known as Aero Commander, a name commonly applied to its line of twin-engine light airplanes. By 1965, it would become the Aero Commander Division of the much larger Rockwell-Standard Corp..

Though Ted Smith, like most great airplane designers, was soon separated from the company he'd created, his creative genius was not wasted. Though, at first, Aero Commander produced light twin-engine airplanes exclusively, the original Aero Commander design spawned a generation of great airplanes (some of which Ted Smith helped design), and the

company soon expanded into a wide range of aircraft, from light singles and cropdusters to full-sized business jets.

Though Ted Smith, like most great airplane designers, was soon separated from the company he'd created, his creative genius was not wasted. Though, at first, Aero Commander produced light twin-engine airplanes exclusively, the original Aero Commander design spawned a generation of great airplanes (some of which Ted Smith helped design), and the

company soon expanded into a wide range of aircraft, from light singles and cropdusters to full-sized business jets.

Meanwhile,

Smith, himself would continue his creative genius. Above, right, he's shown surrounded by models of the various aircraft he helped create, and behind him is the prototype of his next accomplishment -- another great "pilot's airplane" which he created in the 1970's: the sleek, fast Aerostar. The world's fastest piston-engined personal aircraft, the Aerostar (also shown at left) is capable of speeds of over 300 miles per hour, and a pressurized

version can climb to jet altitudes. Though the Aerostar was bounced from company to company, (first being dropped by Aero Commander, and picked back up by Ted Smith, himself -- then bought up by Mooney and later by Piper), Ted Smith's Aerostar design would endure. For a quarter of a century -- living beyond Smith, himself (who died in 1976) -- the Aerostar has reigned as the ultimate piston-engined speed-machine for the fast-flying owner/pilot.

Meanwhile,

Smith, himself would continue his creative genius. Above, right, he's shown surrounded by models of the various aircraft he helped create, and behind him is the prototype of his next accomplishment -- another great "pilot's airplane" which he created in the 1970's: the sleek, fast Aerostar. The world's fastest piston-engined personal aircraft, the Aerostar (also shown at left) is capable of speeds of over 300 miles per hour, and a pressurized

version can climb to jet altitudes. Though the Aerostar was bounced from company to company, (first being dropped by Aero Commander, and picked back up by Ted Smith, himself -- then bought up by Mooney and later by Piper), Ted Smith's Aerostar design would endure. For a quarter of a century -- living beyond Smith, himself (who died in 1976) -- the Aerostar has reigned as the ultimate piston-engined speed-machine for the fast-flying owner/pilot.

In the meantime, though, Smith's original Aero Commander design would also prosper, in a variety of incarnations -- some of which Smith himself would help design.

In 1954, Aero Commander's 500 series expanded from the original Model 520 to include the more-powerful 560 and 580 (early Aero Commander model names roughly matched their horsepower) -- and the less-powerful / more-efficent 500 (a 1958 Model 500 is shown at right). All of them looked about the same -- and generally were, except for the engines. Several were bought by the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Army for military liaison/utility use (designated L-26, U-4 and U-9), particularly as a short-haul transport and reconnaisance plane operating from "unimproved" grass strips in forward areas. One was even used as President Eisenhower's personal transport (Click here for more details, on another website.).

Even more Aero Commanders were bought by civilian operators, excited at the prospect of owning a personal plane with the headroom and grandeur of a private airliner. (The idea of owning a plane chosen for the President of the United States didn't hurt sales, either.) The Aero Commanders' long wings and tailbooms -- and hefty bulk -- gave them a remarkably smooth ride in turbulent air, compared to other private planes of the time. Thrumming along at speeds up to 225 miles per hour, and blessed with good short-field / rough-field performance, the Aero Commander twins provided the owner with quick access to big airports and remote places alike.

A streamlined version of the 500 became the Shrike Commander, which soon became famous for its spectacular appearances at airshows, with former fighter pilot (and later Vice President of Rockwell) Bob Hoover at the controls. After flying an airshow routine in his World-War-II vintage North American P-51 Mustang fighter, Hoover would get into his big, twin-engined Shrike Commander and perform the same stunts -- with both engines running, then again with one engine runing, and finally the whole routine with no engines running -- eventually gliding to a landing, and coasting smoothly to the same spot on the airport from which he'd departed.

A streamlined version of the 500 became the Shrike Commander, which soon became famous for its spectacular appearances at airshows, with former fighter pilot (and later Vice President of Rockwell) Bob Hoover at the controls. After flying an airshow routine in his World-War-II vintage North American P-51 Mustang fighter, Hoover would get into his big, twin-engined Shrike Commander and perform the same stunts -- with both engines running, then again with one engine runing, and finally the whole routine with no engines running -- eventually gliding to a landing, and coasting smoothly to the same spot on the airport from which he'd departed.

Taking advantage of the Shrike's smooth ride and easy controllability, Hoover would take journalists and photographers aloft and demonstrate his most famous stunt: pouring tea into a glass balanced on the throttle quadrant -- while performing a complete, perfect vertical loop, allowing the centrifugal force of the loop

maneuver to keep the tea flowing towards the glass, even when upside-down. Though earning himself a reputation as "the pilot's pilot," Hoover also brought fame, credibility and sex-appeal to the Aero Commander line. The Shrike's many virtues, and the spectacular Hoover exhibitions, soon made the Shrike Commander one of the most lusted-after planes in the world, and brought it the reputation as -- among business twins -- the ultimate "pilot's airplane."

Taking advantage of the Shrike's smooth ride and easy controllability, Hoover would take journalists and photographers aloft and demonstrate his most famous stunt: pouring tea into a glass balanced on the throttle quadrant -- while performing a complete, perfect vertical loop, allowing the centrifugal force of the loop

maneuver to keep the tea flowing towards the glass, even when upside-down. Though earning himself a reputation as "the pilot's pilot," Hoover also brought fame, credibility and sex-appeal to the Aero Commander line. The Shrike's many virtues, and the spectacular Hoover exhibitions, soon made the Shrike Commander one of the most lusted-after planes in the world, and brought it the reputation as -- among business twins -- the ultimate "pilot's airplane."

Sharing the Skies: Competition

Despite its appeal as a pilot's airplane, most pilots couldn't afford the big plane, and by the early 1960's the Aero Commander twin was being beaten in the market by cheaper, lighter, sleeker, more-efficient and speedier light twins from Cessna, Beech and Piper. The big Commander twins were not nearly as efficient and speedy as these newer twins in the same class with it (with comparable price, horsepower and seating capacity). To get you anywhere, Aero Commanders simply guzzled more gas than other popular twins, and generally didn't get you there as fast. Add in the expensive maintenance on the big, geared engines, and it was hard for an Aero Commander to make sense to the person footing the bill.

Each of these manufacturer's smaller twins would soon be stretched to accomodate 6 people, largely neutralizing the value of the Aero Commander's popular 7-seat capacity (which -- in reality -- was seldom fully useable, if full fuel tanks or husky passengers were to be carried).

To improve efficiency and speed, Aero Commander streamlined engine nacelles (which helped), and added the pointed Shrike nose to other models (which made little difference, except to appearances and making room for an optional weather radar). But making the Aero Commander twins lighter and slimmer wasn't really practical: Aero Commanders had been designed around the big-twin idea, and could only get bigger -- not smaller and more efficient.

The "Super" Commanders

The "Super" Commanders

If Aero Commander couldn't make the 500 series smaller, at least they could make it bigger. So The 500 series was expanded to produce the 600 series, hauling between 7 and 10 people (counting the cockpit seats). First came the Model 680 Super, which was actually just a strengthened Model 500, with much-more-powerful, geared-and-turbocharged, 350-hp engines. Various refined versions followed, including the 680E, whose longer "extended" wing allowed a greater load, while providing higher aerodynamic efficiency. Next was the "680F" whose flatter engine nacelles reduced drag substantially, though the wheels had to rotate sideways during retraction, to fit into the slimmer space. (The 680F owned by NASA is shown at right, "tufted" with tiny pieces of yarn to analyze the airflow around the plane).

From the 680F model, the Aero Commander line briefly split into two different cabin-comfort directions: pressurization and lengthening.

First, to permit passengers to ride in the comfortable, clear (but thin) air high above stormy weather, Aero Commander developed a pressurized version of the 680F -- the 680FP, which in 1958 became the 720 Alti-Cruiser, the world's first government-approved, pressurized, non-airline business plane. Pressurizing the cabin overcame the problem of the too-thin-to-breathe air of high altitudes.

Rising above the turbulent air below, Aero Commander passengers and crew enjoyed a gentler, safer ride, while overcoming the barriers to flight created by many high-rising dangerous storms. But the idea was a bit ahead of its time, and only a few were sold. By 1960, though continuing the idea with the lower-powered 680FP, Aero Commander had dropped the Alti-Cruiser for a different approach to luxury.

First, to permit passengers to ride in the comfortable, clear (but thin) air high above stormy weather, Aero Commander developed a pressurized version of the 680F -- the 680FP, which in 1958 became the 720 Alti-Cruiser, the world's first government-approved, pressurized, non-airline business plane. Pressurizing the cabin overcame the problem of the too-thin-to-breathe air of high altitudes.

Rising above the turbulent air below, Aero Commander passengers and crew enjoyed a gentler, safer ride, while overcoming the barriers to flight created by many high-rising dangerous storms. But the idea was a bit ahead of its time, and only a few were sold. By 1960, though continuing the idea with the lower-powered 680FP, Aero Commander had dropped the Alti-Cruiser for a different approach to luxury.

An un-pressurized version of the 680F was lengthened into the 680FL, making room for up to 9 people in all (shown here, recently modified with "winglet" wingtips).

Interestingly, lengthening the 680F airframe into the 680FL, despite the addition of weight, reportedly did nothing to increase the airplane's drag. An aerodynamic analysis revealed that extra drag created by the extra surface area was offset by the more-aerodynamic hull shape created by stretching the airplane a bit.

Interestingly, lengthening the 680F airframe into the 680FL, despite the addition of weight, reportedly did nothing to increase the airplane's drag. An aerodynamic analysis revealed that extra drag created by the extra surface area was offset by the more-aerodynamic hull shape created by stretching the airplane a bit.

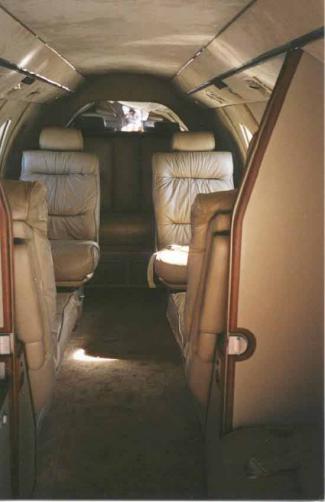

With an aisle between the seats, it was like a mini-airliner. (In fact, several of the 680FL's and their successors were actually used as short-haul airliners). This class of plane came to be known as "airliner-cabin class," or simply "cabin-class." The Beech Model 18 had first claim to the class, and by 1960 Beech had debuted its elegant Queen Air. The Aero Commander 680FL was introduced the very next year. Cessna and Piper would soon follow with their cabin-class mini-airliners (the Cessna 400 series and the Piper Navajo). In 1965, the 680FL was appropriately renamed the Grand Commander.

Finally, in late 1965, the stretched (680FL) and pressurized (680FP) versions were reunited in the 680FLP Pressurized Grand Commander, which later became known as the Courser Commander. The last production version would be the 685 (shown here),

-- actually a Model 690 Turbo Commander (see below), with piston engines in place of the usual engines, and with drag-reducing up-swept "winglets" on its wingtips. By the end of 1979, when production of piston-engined, stretched Commanders ended, 66 copies of the Model 685 had been built, along with dozens of the various 680FL and 680FLP models.

-- actually a Model 690 Turbo Commander (see below), with piston engines in place of the usual engines, and with drag-reducing up-swept "winglets" on its wingtips. By the end of 1979, when production of piston-engined, stretched Commanders ended, 66 copies of the Model 685 had been built, along with dozens of the various 680FL and 680FLP models.

By the mid-1960's, Aero Commander twins -- colloquially known as "Twin Commanders" -- had become quite popular as executive transports, but still suffered from sluggish speed in the 500 series, and so-so speed in the 600-series.

Also, the big 600-series were powered by notoriously-troublesome geared engines -- the only efficient engines big enough for the job. By taking ordinary airplane engines, then "turbocharging" them (forcing more air/fuel mixture into the engines with compressor fans, spun by exhaust-driven turbines), and then gearing the engines to turn at higher speeds than they were originally designed for, the engine-company's engineers were able to squeeze more power from the piston engines -- but at a severe cost in durability and reliability.

The problem came to a head in the mid-1960's, when Beech Aircraft began introducing powerful, compact "jet-prop" turbine engines (Pratt & Whitney PT-6A turboprops, to be exact) to executive planes -- with their wildly successful, high-flying Beech King Air (shown at right). These "turboprops" were jet engines driving propellors, for an ideal compromise between the low-speed, low-altitude effiency of propellor-driven engines, and the high-speed, high-altitude capabilities of the jet engine.

The problem came to a head in the mid-1960's, when Beech Aircraft began introducing powerful, compact "jet-prop" turbine engines (Pratt & Whitney PT-6A turboprops, to be exact) to executive planes -- with their wildly successful, high-flying Beech King Air (shown at right). These "turboprops" were jet engines driving propellors, for an ideal compromise between the low-speed, low-altitude effiency of propellor-driven engines, and the high-speed, high-altitude capabilities of the jet engine.

The Beech King Air swept the market like a storm, as executives and tycoons and foreign potentates (and even military generals) began lusting after this grand "personal airliner" that could soar high above the clouds (higher than any pressurized Commander), and blast along at "airliner" speeds (though the bulky King Air was really only slightly faster than the Aero Commanders). The King Air quickly began siphoning sales away from all other top-of-the-line business twins, including Aero Commander's best. It was definitely catch-up time for Aero Commander.

Turbo Commander

Turbo Commander

It took Aero Commander until 1967 to respond, by putting powerful, new Garrett AirResearch TPE-331 turboprops on its 680FLP. The result was the Aero Commander 681 (commonly known as the Turbo Commander, or -- briefly -- Hawk Commander). It soon evolved into the slightly more powerful, and more-refined 690. (A 1986 Model 690B II is shown at left.) This roomy, fast, high-flyer helped Aero Commander regain much of its status in the business aircraft market.

Faster, by far, than Beech's King Air, let alone any of the large Cessna or Piper piston-engined twins, the well-mannered Turbo Commander was blessed with a cockpit that afforded great visibility for pilots, and remarkably simple cockpit systems, while exuding the sophisticated image of an airliner's flight deck.

The low-slung 690 nevertheless lacked the awe-inspiring "ramp presence" of the King Air's towering high stance, and -- worse -- had engines (Garrett AiResearch TPE-331's) with greater operating costs than that Beech's King Air (powered by Pratt & Whitney PT-6A's). A final disadvantage was the placement of the Turbo Commander's engines and propellors. While Beech's engines and propellors were well forward of the passenger compartment, the high-wing design of the Turbo Commander necessitated putting engines and propellors -- along with all their noise -- right next to the passenger compartment.

Still, with a roomy cabin and the advantage of a spectacular earthward view for passengers through huge picture windows (the King Air's low wing prevented much of a view from its small, round porthole windows), the Turbo Commander retained a great appeal. And no one could deny their speed. Until the Japanese Mitsubishi MU-2 turboprop came on the scene, no prop-driven business twin afforded greater speed -- let alone more scenic views -- than the Turbo Commander.

Still, with a roomy cabin and the advantage of a spectacular earthward view for passengers through huge picture windows (the King Air's low wing prevented much of a view from its small, round porthole windows), the Turbo Commander retained a great appeal. And no one could deny their speed. Until the Japanese Mitsubishi MU-2 turboprop came on the scene, no prop-driven business twin afforded greater speed -- let alone more scenic views -- than the Turbo Commander.

Throughout the 1970's and early 1980's, the 690/695/840/900/980/1000 series of turboprop twins followed, each expanding the performance and capacity of the plane before it, but all of them retaining the distinctive basic Aero Commander design: high-wing twins, with long graceful wings and tall tails, roomy, rectangular cabins (versus the cramped, round cabins of competing planes), magnificent flying characteristics and hefty load capacities.

A 1980-model 840 is shown here, incorporating tiny up-swept "winglets" at the wingtips, to reduce drag caused by wingtip vortices at cruise speed. By the time the Aero Commander's Model 900 came on the scene, more efficient and reliable versions of the Garrett engine (particularly the TPE-331-10, colloquially known simply as "Dash 10") were available, increasing the reliability, affordability and value of the Turbo Commander. Many older models have since been modified -- re-engined -- with the "Dash 10 mod."

|

|

1121 Jet Commander.

For its whole story, see: "Jet Commander History" |

Ironically, Aero Commander produced a pure-jet version before it could come up with a turbo-prop model. In 1963, Aero Commander first flew the Model 1121 Jet Commander, one of the earliest business jets -- or "bizjets." It used a fuselage similar to the Pressurized Grand Commander (though with smaller windows, to allow for the higher pressurization required at high-flying jet altitudes), mated to completely-different, shorter wings (projecting straight out from the mid-section of the fuselage) and twin turbojet engines (mounted in pods on each side of the tailcone). Though it lacked the long range of some competing business jets, the Jet Commander was popular with pilots for its superior handling characterstics, and popular with passengers for its interior room and spectacular view (the entire cabin was forward of the wing).

By 1965, Aero Commander had delivered its first Jet Commander, for a price of about a half-million dollars. Over the next few years, up to 8 jets a month would come off the assembly lines. Though the Jet Commander design would eventually be sold off to a string of future owners, it would continue to be a popular aircraft, with over 500 built, sold and flown world-wide by the end of the century.

The Cost of Business

At about the same time as the Jet Commander's debut, in 1965, big changes were underway for the independent Aero Commander Co. Preparing for the production of aircraft -- particularly new business jets in a hotly-competitive market -- was an enormously expensive business. To finance the rapid development of aircraft, and the very costly business of tooling up and stocking up for aircraft production, the company needed access to large amounts of cash. Just buying engines for aircraft on the assembly line required millions of dollars. And instruments and radios cost money, too, as did all the raw materials, and even the factory facilities themselves. Finally, payroll for hundreds, even thousands, of workers had to be met, while the airplanes slowly took shape on the assembly line.

While a company could finance a steady, continuous production rate from current sales, it could not finance an expansion -- in product lines or production volume -- that way. The sales would come too late. The highly competitive, high-dollar business aircraft market waited for no one, and the first company to the market with a new product, or the first company to reduce costs (and prices) through mass production, quickly became a dominator in the market -- and would then begin to take away the sales of other aircraft makers. This was an industry with clear winners and losers. The brutal aviation-industry shakeouts of the early 1930's, and the late 1940's -- in which most light-aircraft companies were wiped out -- had made that fact brutally clear.

Although Aero Commander had had the business-twin market largely to itself during the early 1950's, it was now facing some tough, established competition. In the business-twin market, Beech Aircraft -- the leader -- had a rock-solid footing stretching back for a generation, and its popular King Air turboprop had almost total dominance among turboprop executive aircraft. Cessna Aircraft, making do with piston-engined aircraft, had a loyal following of customers, progressing up from its single-engine line (the most popular in the world) to its light twins to its newly-developed cabin-class twins -- in direct competition with Aero Commander. Piper Aircraft -- the second-leading producer of single-engine aircraft -- was quickly moving into the twin-engine market with popular, low-priced, efficient twins. Already its "entry-level" light twins owned the lion's share of that market, and Piper was moving into the Aero Commander's "cabin class" with the 6-seat Aztec and the roomy Navajo.

On the other end, in the business-jet market, four companies had beaten the Jet Commander to market. Lockheed (famous for military aircraft and commercial airliners) and North American Aviation (a leading producer of military jets) were closing in from above with their JetStar and Sabreliner, respectively. Overseas, Britain's deHavilland had introduced the DH-125 business jet (soon acquired by Hawker-Siddley as the HS-125). And not to be outdone, the French had produced a mini-bizjet, the Moraine Saulnier MS.760 Top business-aircraft competitor Beech Aircraft had already introduced the MS.760 briefly in the U.S., and was soon to team with Hawker Siddley to sell the HS-125 in the U.S. (as the Beech-Hawker BH-125). And Bill Lear was on the verge of introducing a plane that would rock the aviation world, and become a household word: the Learjet.

This was no time for a business-aircraft company to be caught short on investment money. But banks were loathe to invest in the technical, highly-specialized, and volatile general aviation industry. They were especially reluctant to loan money to a small-plane manufacturer who lagged well behind the "Big Three" (Cessna, Beech and Piper) in longevity, sales and assets.

How then to get access to the investment capital needed to stay in the game? The solution was to merge with another company. By 1965, Aero Commander had arranged to become the Aero Commander Division of the much larger Rockwell-Standard Corp.. With the new ownership providing deeper pockets from which to invest, Aero Commander now had a brighter future. Even the process of getting bank loans would be easier, now that the bankers could see that there was a backer to pay the bills if Aero Commander failed.

At the same time, Rockwell-Standard, a company mired in the aging industrial technology of its old product line of mechanical parts, tools and industrial machinery, could invest its old wealth in a booming new technology -- aviation -- that Rockwell was not suited to enter on its own (for a sense of Rockwell's creative limitations, consider that board chairman Willard Rockwell, Sr. had begun his industrial career in 1908). And Aero Commander's highly regarded aircraft -- including its noteworthy progress towards hot new designs -- seemed a smart, long-term investment.

But with marriage comes baggage. After its successful acquisition of little Aero-Commander, Rockwell-Standard became even more interested in aviation, and set its sights on something far more ambitious: buying North American Aviation.

North American Aviation

was one of the most famous names in cutting-edge military aviation. North

American started tinkering with military aircraft just before World War II. Its

first truly successful design was the T-6 Texan trainer (left, sometimes called the

AT-6 or Harvard), an advanced-training plane that prepared most of the American

and British fighter pilots of World War II to step into fighter planes. Then

came North American's most famous design: With the start of the World War II in

Europe, North American began hastily developing the P-51 Mustang fighter, which

became the best fighter aircraft produced by any country in the war. The company also produced the twin-tailed, twin-engined B-25 Mitchell medium bomber. Following

that were a string of other successes, including the F-86 Sabrejet fighter, which

dominated the skies during the Korean War, and the world's first supersonic fighter: the F-100 Super Sabre.

North American Aviation

was one of the most famous names in cutting-edge military aviation. North

American started tinkering with military aircraft just before World War II. Its

first truly successful design was the T-6 Texan trainer (left, sometimes called the

AT-6 or Harvard), an advanced-training plane that prepared most of the American

and British fighter pilots of World War II to step into fighter planes. Then

came North American's most famous design: With the start of the World War II in

Europe, North American began hastily developing the P-51 Mustang fighter, which

became the best fighter aircraft produced by any country in the war. The company also produced the twin-tailed, twin-engined B-25 Mitchell medium bomber. Following

that were a string of other successes, including the F-86 Sabrejet fighter, which

dominated the skies during the Korean War, and the world's first supersonic fighter: the F-100 Super Sabre.

In 1967, Aero Commander's parent company, Rockwell-Standard Corp. began its move on North American Aviation. One major obstacle stood in the way: the Jet Commander. North American (as noted earlier) was also building a business jet -- the Sabreliner -- which was in competition with the JetCommander. Because of anti-monopoly laws, the U.S. government would not approve the merger of the two companies, unless one of the business jet lines was sold off. (This was a time when these two jet planes comprised about half of the models on the newly-developed bizjet market.)

|

| North American T-39 Sabreliner, used as a generals' taxi and in other support roles. The T-39B had military radar and doppler navigation equipment to train F-105 fighter pilots. (U.S. Air Force photo) |

Which jet to keep and which to let go? The U.S. Air Force, which had bought a number of North American's Sabreliners as the T-39 (see The Sabreliners, below), angrily insisted that the newly merged companies keep the Sabreliner, so that the Air Force could not only purchase more (under its existing contracts), but so that the Air Force could count on continuing technical support and a continuing production of spare parts -- without which its large investment in T-39's would quickly be lost.

The newly-merged company, North American Rockwell, could not afford to anger its main customer, the U.S. Air Force, upon whom it would surely depend for future big-ticket sales of military aircraft. A single lost military deal could cost hundreds of millions of dollars. One jet fighter could make the company millions, compared to the "mere" half-million-dollar price of the Jet Commander. The loss of military business would hurt the new North American Rockwell company much more than the loss of the bizjet trade. And by keeping the Sabreliner, they could still have some presence in the bizjet market, as well as the military market. But if they discarded North American's Sabreliner to keep the civilian Jet Commander, Rockwell's massive investment in North American -- who only made military aircraft -- could become a complete loss.

Reluctantly, North American Rockwell sold off the Jet Commander line. But the highly-regarded bizjet quickly found an eager buyer -- a long, long way away.

The government of Israel, whose defense in ongoing wars with its Arab neighbors depended heavily on airpower, had begun creating its own aviation industry, with Israel Aircraft Industries, Ltd. (IAI). The company started out modifying foreign military aircraft to meet Israel's unique needs, and producing licensed versions of foreign aircraft. But the resources invested in military work for Israel could also be made to pay for themselves by using IAI's factories to build civilian products for export. IAI saw an opportunity in the 1121 design, and bought it, along with all the tooling and parts, and 49 aircraft still not completed, and moved production to Israel.

In 1969, IAI re-started production of the plane, renaming it the 1121 Commodore Jet. In 1970, adding tip tanks for greater range, IAI modified it into the popular 1123 Westwind. Later versions have included the popular 1124 Westwind (which introduced modern, efficient Garrett AiResearch TFE-731 turbofan engines, extending range by 10%, and reducing runway length requiremnts), and the 1124B Westwind II (adding winglets and an improved wing for better performance and range). About 200 of the Model 1124's were sold.

In the mid-1980's, a radical transformation produced the 1125 Astra, which kept only the 1124's original tail and engine nacelles, and switched to a new, low-mounted, swept wing, supporting a longer, more-tubular fueselage (although the 1121 lineage is still visible). The result was a bigger cabin -- putting the plane in a better position to compete with the stand-up room of bigger jets -- and better performance, paticularly extending range by nearly a thousand miles. About this time, IAI created a marketing company to sell the jet, called Astra Jet Corp.

In 1997, IAI spun off the Jet Commander line to a new company which aviation executive Brian Barents (later president of Learjet) helped them form in partnership with the Pritzker family (who had helped develop Hyatt Hotels and Braniff Airways). The result was Galaxy Aerospace, which was formed around the newly transferred design. The company began design work on the 1126 Galaxy -- a new design, emulating the style of the Astra in an enlarged, longer-range version. The design, owned for a few years by Galaxy Aerospace, Ltd., is now owned by General Dynamics, who have renamed the Astra as the G-100, and the Galaxy as the G-200. A generation after the debut of the Jet Commander, its basic design is still a hot product, and over 400 of the Jet Commanders and their offspring are currently flying around the world, today.

|

| The stretched 1984 North American Sabreliner 65. (Quintin Soloviev, via Wikipedia , thru International license 4.0) |

North American's Sabreliner line, often a bit of a mis-fit to the Aero Commander line, was one of the nation's first business jets. It originated as an attempt (eventually successful, as the T-39) to win a contract to provide the U.S. Air Force with a small, cabin-class jet aircraft which could be used as a light, fast transport for utility use (particularly as a "general's jet"), and as a systems-training platform for navigators, bombardiers and weapons-systems officers headed for duty aboard jet fighters and bombers (in the late 1990's, the Navy would restore Sabreliners to a similar use).

North American's Sabreliner line, often a bit of a mis-fit to the Aero Commander line, was one of the nation's first business jets. It originated as an attempt (eventually successful, as the T-39) to win a contract to provide the U.S. Air Force with a small, cabin-class jet aircraft which could be used as a light, fast transport for utility use (particularly as a "general's jet"), and as a systems-training platform for navigators, bombardiers and weapons-systems officers headed for duty aboard jet fighters and bombers (in the late 1990's, the Navy would restore Sabreliners to a similar use).

The early model reputedly was based in large measure on the design of North American's F-100 Super Sabre, the first supersonic jet fighter. Using the F-100's wings, landing gear and tail, the plane was configured like a minature airliner, with a roomy passenger cabin, behind the two-seat (side-by-side) cockpit.

Though never as fast as its miltary sibling, the Model 40 Sabreliner -- at over 500 miles per hour -- was one of the fastest, highest-flying cabin-class planes of the day (only Lockheed's JetStar, the only other cabin-class small jet plane of the day, was faster).

It quickly found a civilian market niche as a minature, private jet airliner for high-powered executives -- helping to launch the concept of bizjets, which William Lear would soon make practical with the compact Learjet.

It quickly found a civilian market niche as a minature, private jet airliner for high-powered executives -- helping to launch the concept of bizjets, which William Lear would soon make practical with the compact Learjet.

Though discontinued in the early 1980's, in 1983 the rights to the civilian Sabreliner Division of Rockwell International (based in Perryville, Missouri, near St. Louis) were purhcased by a St. Louis, MO, investment group -- and the resulting company was named Sabreliner Corp. This company keeps refurbishing Sabreliners to this day, keeping the design alive and flying.

As late as the turn of the century, various aviation companies (like St. Louis' Sabreliner Corp. and Wichita's Executive Aircraft) were doing a steady business specializing in the Sabreliner. Age has taken its toll, though, and most Sabreliners have "worn out" from thousands of hours of operation, the impact of thousands of landings, and the inevitable toll of corrosion. Nevertheless, a few can still be bought, inexpensively (compared to other bizjets), and continue in service to this day.

NOTE: For the full, tangled story on North American Aviation, and the Sabreliner, see Aerofiles.com, particularly http://aerofiles.com/noram-co.html.

Little Commanders

Little CommandersAero Commander had long been competing with the "Big Three" general aviation aircraft manufacturers -- Beech, Cessna, and Piper --- for the "cabin-class" twin market. A major disadvantage for Aero Commander was that the Big Three each had a "full line" of aircraft, from two-seat trainers to cabin-class twins. Owners could "move up" to bigger Cessnas / Beeches / Pipers as their interests and finances permitted, and many did. Starting out in a particular brand of plane commonly breeds brand loyalty, and owners who started with small Cessnas (or Beeches, or Pipers) were very likely to choose big Cessnas (or Beeches, or Pipers as the case may be) when they had the chance to move up to a cabin-class twin.

Aero Commander wanted a way to draw customers into their line, as they moved up.

So -- in the mid-1960's -- Aero Commander began buying up other reputable

designs. Among its early acquistions, Aero Commander bought

Volaircraft (formerly Volaire Aircraft), maker of

the small, high-winged, 2-4-seat Model 1050 (similar to the Cessna 172,

and sturdy, though not as efficient). These planes -- distinguished by their

backswept vertical tails (like Mooney aircraft) provided a respectable "bottom

end" to the Aero Commander line.

Aero Commander wanted a way to draw customers into their line, as they moved up.

So -- in the mid-1960's -- Aero Commander began buying up other reputable

designs. Among its early acquistions, Aero Commander bought

Volaircraft (formerly Volaire Aircraft), maker of

the small, high-winged, 2-4-seat Model 1050 (similar to the Cessna 172,

and sturdy, though not as efficient). These planes -- distinguished by their

backswept vertical tails (like Mooney aircraft) provided a respectable "bottom

end" to the Aero Commander line.

But these light, fixed-gear singles never became nearly as popular as the well-established competing models from Cessna (Models 150/172/182), Piper (the Cherokees) and Beech (the Musketeers). From 1965 to 1968, Aero Commander produced the 150-horsepower plane as the Aero Commander 100, with the name Cadet added briefly. In 1968, in keeping with a fleeting attempt to rename all Aero Commanders with the names of birds, the 100 became the Darter Commander, and -- with a bigger, 180-hp engine and a normally-swept tail -- the Lark Commander. Neither name-change, nor tail-sweep nor extra horsepower helped sales, and the next year both planes were dropped from the Aero Commander line.

The Model 200D

The Model 200D

For its next acquisition, Aero Commander sought an airplane that was the "next rung up the ladder" from the Lark and Darter. It found the next rung in the Meyers Aircraft Company, of South Carolina. The Meyers company had a long history, dating back to 1939, which included the respected and durable Meyers OTW biplane -- used as a trainer throughout World War II, and as a sport and utility plane long after the war. But tiny Meyers Aircraft had moved on to modern aircraft, and had done so with remarkable panache.

Meyers

produced a sporty two-seat, low-winged, retractable-geared taildragger, the

MAC-145. With an automotive style cockpit and canopy-enclosed cabin, the

145 was a fast and sexy plane for the playboy pilot -- a sort of "T-bird" sports

car of the air. (A 1954 Model 145, still flying, is shown here). Well-made, the

145 was reportedly (as of 1999) the only American production aircraft never

cited by the FAA for an Airworthiness Directive ("AD notice") requiring

correction of a design or manufacturing defect, or dangerous aging flaw. But its

tailwheel landing gear design was considered obsolete in an era when

easy-handling tricycle gear was becoming widely expected as the norm in personal

aircraft. Though Aero Commander's purchase of the 145 design was not its finish

(see below) Aero Commander was interested in Meyers Aircraft for something

bigger.

Meyers

produced a sporty two-seat, low-winged, retractable-geared taildragger, the

MAC-145. With an automotive style cockpit and canopy-enclosed cabin, the

145 was a fast and sexy plane for the playboy pilot -- a sort of "T-bird" sports

car of the air. (A 1954 Model 145, still flying, is shown here). Well-made, the

145 was reportedly (as of 1999) the only American production aircraft never

cited by the FAA for an Airworthiness Directive ("AD notice") requiring

correction of a design or manufacturing defect, or dangerous aging flaw. But its

tailwheel landing gear design was considered obsolete in an era when

easy-handling tricycle gear was becoming widely expected as the norm in personal

aircraft. Though Aero Commander's purchase of the 145 design was not its finish

(see below) Aero Commander was interested in Meyers Aircraft for something

bigger.

Aero Commander was more interested in the pilots who were building loyalty to Beech, Cessna and Piper aircraft (including their heavy twins) -- after being introduced to those companies through their 4-seat, retractable, tricycle-geared aircraft (the Beech Model 33/35 Bonanza, Cessna 210 Centurion and Piper Comanche). These owner-pilots were among the people most likely to migrate up to the light and medium twins (such as the Aero Commander twins), as their fortunes progressed. Once used to a particular brand in smaller, high-performance singles, owner-pilots had a tendency to stay with the same brand in later purchases of twin-engine aircraft. So, naturally, Aero Commander wanted a high-performance single of its own, to compete with the Bonanza, 210 and Comanche.

Meyers

Aircraft had taken the sleek, smart design of the Meyers 145, and stretched it

into the 4-seat Meyers 200 with retractable tricycle gear (a 1966 Model

200D is shown here). And this was the plane Aero Commander adopted, as the

Aero Commander 200D -- a sleek, 4-place, low-wing retractable-geared

hot-rod, with a canopy-enclosed, automobile-like cabin. With an automotive-style

interior, the occupants felt the comfort of the familiar surroundings. But with

hot-rod performance, aided by slick, flush-riveted wings and hefty engines

ranging from 225-hp to a very hot 285 horsepower, the Model 200 was no mere

automobile aloft, blasting through the air at well over 200 miles per hour --

almost unheard of for a 4-seat, single-engine personal aircraft. Highly regarded

by aviation analysts, the scarce Model 200 (only 55 had been built before Aero

Commander bought the design) was a truly "high-performance" single.

Meyers

Aircraft had taken the sleek, smart design of the Meyers 145, and stretched it

into the 4-seat Meyers 200 with retractable tricycle gear (a 1966 Model

200D is shown here). And this was the plane Aero Commander adopted, as the

Aero Commander 200D -- a sleek, 4-place, low-wing retractable-geared

hot-rod, with a canopy-enclosed, automobile-like cabin. With an automotive-style

interior, the occupants felt the comfort of the familiar surroundings. But with

hot-rod performance, aided by slick, flush-riveted wings and hefty engines

ranging from 225-hp to a very hot 285 horsepower, the Model 200 was no mere

automobile aloft, blasting through the air at well over 200 miles per hour --

almost unheard of for a 4-seat, single-engine personal aircraft. Highly regarded

by aviation analysts, the scarce Model 200 (only 55 had been built before Aero

Commander bought the design) was a truly "high-performance" single.

But the Model 200 was a very late entrant in a field that was already well-populated with popular designs. In addition to the Beech, Cessna and Piper models mentioned above, Piper added a retractable-geared version of its popular Cherokee 180 (the Cherokee "Arrow"), while the Bonanza, 210 and Comanche were stretched to accomodate 6 people (if the last two passengers were mighty small). All along, too, Mooney Aircraft (which specialized almost exclusively in fast, efficient 4-seat retractables) -- and Bellanca Aircraft (with its old-fashioned, luxurious, wooden-winged, tube-and-fabric, 4-seat speedsters) -- had been scooping up the rest of the market, leaving almost no room for the late-arriving Aero Commander 200D (never helped by its dull name).

In 1967, it was "upgraded" to the Aero Commander 200E by the mostly-cosmectic act of sweeping the vertical tail back, giving the 200 a more modern appearance. But it was to no avail. In the late 1960's, after selling a total of just 77 of the Aero Commander 200's (compared with thousands of Beech Bonanzas, and hundreds of Piper Comanches, Cherokee Arrows, Cessna 210's, Cessna 177/Cardinal RG's, and Mooneys sold in the same time frame) Aero Commander quietly withdrew the Model 200 from the market.

In the 1968, after the Aero Commander line dropped the Model 200, though, some enthusiasts started a new company around the old design, called Interceptor Corp., in Norman, Oklahoma (later moving to Boulder, Colorado in 1973 under the name Interceptor Co.). Adding a 400-horsepower version of the same turboprop engine which powered the Turbo Commander, the Interceptor folks boosted the hot-rod single to speeds approaching 300 miles per hour. The hot "new" plane became the Interceptor 400 (shown at right). Though creating much excitement in the general aviation community, only a few were sold before the general aviation market collapsed in 1982. The rights were then passed on to Prop-jets, in San Antonio TX, where -- at last report -- they lay dormant.

The sporty,

two-seat, taildragging Model 145, too, was revived, in the late 1990's, by

MICCO as the SP20 and SP30 (shown at left). With a

few aerodyanmic refinements, and a new engine, the new/old hot-rod airplane

arrived on the scene to rave reviews from aviation editors eager for a sport

plane that combined "exciting performance" (industry codeword for

"high-performance, stunt-flying capability") with affordability (compared to

other new retractable aircraft) and long-range speed. The airplane is in

production today.

The sporty,

two-seat, taildragging Model 145, too, was revived, in the late 1990's, by

MICCO as the SP20 and SP30 (shown at left). With a

few aerodyanmic refinements, and a new engine, the new/old hot-rod airplane

arrived on the scene to rave reviews from aviation editors eager for a sport

plane that combined "exciting performance" (industry codeword for

"high-performance, stunt-flying capability") with affordability (compared to

other new retractable aircraft) and long-range speed. The airplane is in

production today.

And now for something completely different:

Cropdusters.

With a stout "crash cage" to protect the low-flying pilot from

accidents, each plane had a large "hopper" in front of the pilot for carrying up

to a half ton or more of agriultural chemicals, dispensed through long tube-like

"spray booms" stretching out along the trailing edges of the wings. In minutes,

a cropduster could spray more crops than a tractor can in a day, making them

enormously valuable for farming large tracts of land, especially in areas not

troubled by constant winds that could diffuse the spray, or tip the low-flying

cropduster, or in places where heavy rains and irrigation had created

tractor-halting mud.

With a stout "crash cage" to protect the low-flying pilot from

accidents, each plane had a large "hopper" in front of the pilot for carrying up

to a half ton or more of agriultural chemicals, dispensed through long tube-like

"spray booms" stretching out along the trailing edges of the wings. In minutes,

a cropduster could spray more crops than a tractor can in a day, making them

enormously valuable for farming large tracts of land, especially in areas not

troubled by constant winds that could diffuse the spray, or tip the low-flying

cropduster, or in places where heavy rains and irrigation had created

tractor-halting mud.

Two noted experts in ag planes were Ruell T. Call, of Call Aircraft Co., Afton Wyoming, and Leland Snow, of Snow Aeronautical Co., Olney TX, whose similar ag planes were popular with cropdusters. In 1965, Aero Commander bought the rights to both company's designs. The two companies' product lines were consolidated in Albany, Georgia, where Fred Ayres became the Aero Commander's chief seller of ag planes.

Aero Commander produced the big, beefy Snow Commander (later renamed the Ag Commander, then, in 1967, the Thrush Commander, with giant radial engines of up to 600 horsepower -- making it the most powerful mass-produced cropdusting plane in the world, able to carry up to a ton-and-a-half of chemicals for spraying.

While Cessna

(with its Agwagon series) and Piper (with its Pawnee and Brave) captured the low

end of the cropdusting market, the Aero Commander cropdusters -- with their

beefy 300-600 horsepower engines -- were popular for hauling heavy loads, and

working in tight places and high altitudes where maximum power was needed for

maneuverability. Their radial engines, though aerodynamically inefficent and

mechanically "obsolete", enabled operators to inspect them and work on them

quickly and easily, permitting greater safety and continuity of operation --

especially in high-volume operations. Aero Commander's only competition for the

"high end" market were inefficient, drag-intensive, biplanes -- particularly

aging World-War-II vintage military-surplus Stearman biplanes (the first popular

cropdusters) and Grumman's stout-but-slow Ag-Cat biplane.

While Cessna

(with its Agwagon series) and Piper (with its Pawnee and Brave) captured the low

end of the cropdusting market, the Aero Commander cropdusters -- with their

beefy 300-600 horsepower engines -- were popular for hauling heavy loads, and

working in tight places and high altitudes where maximum power was needed for

maneuverability. Their radial engines, though aerodynamically inefficent and

mechanically "obsolete", enabled operators to inspect them and work on them

quickly and easily, permitting greater safety and continuity of operation --

especially in high-volume operations. Aero Commander's only competition for the

"high end" market were inefficient, drag-intensive, biplanes -- particularly

aging World-War-II vintage military-surplus Stearman biplanes (the first popular

cropdusters) and Grumman's stout-but-slow Ag-Cat biplane.

At the same time, Aero Commander produced the smaller Call-Air designs as the Sparrow Commander and Quail Commander, competing with smaller cropdusters like the Piper Pawnee and the Cessna AgWagon. However, that was a tougher market, and in 1971 Rockwell sold the two Call-Air designs to AAMSA (AERON-UTICA AGR-COLA MEXICANA S.A.) and Industrias Unidas S.A., of Mexico, where they were subsequently produced.

Eventually, Aero Commander got out of the cropduster-building business, and in 1977 the Thrush Commander design was acquired by Aero Commander salesman Fred Ayres, who resumed production on his own. Ayres later produced a turboprop-powered variation of the Thrush as the Turbo Thrush, which is still in production today, at Ayres Aircraft, in Albany, Georgia. To date, since their inception, over 2,000 of the Thrush and Turbo Thrush aircraft have been sold -- spread over 70 countries worldwide.

Creating from Scratch:

the Commander singles

Eventually, Aero Commander discontinued its entire single-engine line of acquired designs, and developed its own single-engine line from scratch: a stout, low-winged line with distinctive cross-shaped ("cruciform") tail. The 111 and 112 were fixed gear, while The 114 was a retractable. Though overbuilt, and cursed with excessive weight, poor aerodynamics and mediocre performance on its 200-hp engine, the 114 (now known simply as the Commander) offered a particularly comfortable cabin, and generally mild behavior for a retractable-geared plane.

Eventually, Aero Commander discontinued its entire single-engine line of acquired designs, and developed its own single-engine line from scratch: a stout, low-winged line with distinctive cross-shaped ("cruciform") tail. The 111 and 112 were fixed gear, while The 114 was a retractable. Though overbuilt, and cursed with excessive weight, poor aerodynamics and mediocre performance on its 200-hp engine, the 114 (now known simply as the Commander) offered a particularly comfortable cabin, and generally mild behavior for a retractable-geared plane.

Like the Model 200 before it, the new Commander single-engine line was never very popular, and failed to get a strong foothold in the highly-competitive light-retractable market. Its competition included the cheap, gentle Piper Arrow, the fast-and-efficient Mooneys, Cessna's beautiful, efficient, graceful Cardinal RG and strong, safe Skylane RG, and the classy, ever-popular Beech Bonanza.

Nevertheless, it retains some appeal, and is still manufactured today. The 111/112/114 line was salvaged by Aero Commander workers, in Bethany, who kept it alive after the sell-off of the twin-Commander line. They named their company Commander Aircraft, and retained the model numbers of the Aero Commander single-engine line. The company comes and goes with the changing aviation market.Changing Hands

In 1973, North American Rockwell (headed by Williard Rockwell, Sr.) merged with yet another company -- the Rockwell Mamufacturing Company (headed by Williard Rockwell, Jr.) -- the resulting corporation become Rockwell International.

Through the following years, the Aero Commander and Sabreliner divisions rose and fell with the waves of corporate change and the winds of the volatile aviation market. Rockwell International gradually discontinued or sold off one Aero Commander line after another, until only the Sabreliner and the Twin Commander lines remained. In 1978, Williard Rockwell, Sr. -- having begun his industrial career before World War II -- died at the ripe old age of 90. With his death, and the resignation the following year of his son, Willard, Jr., the company began to wander away from its aviation activities, focusing increasingly on industrial equipment and automation.

In late 1980, the Twin Commander line was sold to Gulfstream Aircraft, who wanted it to complement the company's Gulfstream super-bizjet line (sold off previously by Grumman Aircraft). The Aero Commander line became known as the Gulfstream Commander line, until discontinued in 1985. During this time, Gulfstream developed and produced the ultimate upgrade of the Twin Commander prop-driven line: the Commander Jetprop 1000, with a cruising speed of over 350 mph, and a range of over 1,000 miles.

At the end of 1980, Aero Commander (by now the General Aviation Division of Rockwell International Corp.) was sold off to Gulfstream American -- makers of the Gulfstream exectuive jet on the one end, and the small Grumman-American light planes on the other end. Grumman had spun off Gulfstream to rid itself of general-aviation aircraft -- a distraction from its main business of making military aircraft. The Aero Commander line fit well into the gap between Gulfstream's tiny Tigers and Trainers and the giant, top-of-the-line Gulfstream III business jet, though Gulfstream discontinued the small Grumman-American line at about the same time they bought the Twin Commander line.

In 1982, the Reagan-era recession -- and rapidly escalating cost of post-crash lawsuits -- brought about the catastrophic collapse of the general aviation market. Many smaller manufacturers were driven out of business. In 1984, industry-leader Cessna Aircraft, halted all production of its piston-engined aircraft, and eventually halted even turboprop sales. Piper Aircraft went in and out of business. Of the light/medium-twin builders, only Beech (buoyed by military sales) and Gulfstream kept producing.

But the "recovery" from the recession was the slowest in modern history, and aircraft sales suffered enormously. In 1985, all manufacturing of the "Twin Commanders" was stopped. Gulfstream continued to produce its large and small Grummans, but eventually sold off the rights to the Twin Commanders to a company called -- not surprisingly -- Twin Commander Aircraft Corporation, who developed the "Rennaisance Commander" modification. This "mod" is actually the unusual business of "re-manufacturing" Aero Commanders -- stripping them to their skeletons, and reassembling them largely with new parts -- resulting in an aircraft which is (legally, at least) "brand-new." This has been particularly important as aging Twin Commanders suffer from two potentially deadly weaknesses as they age: the many rubber fuel bladders in the multi-compartment wings deteriorate, and a poor design in the wing structure gradually weakens the wing (a "spar cap" on the wing's main spar is aluminum, which corrodes on contact with the steel wing spar). The "Renaissance Commander" remanufacturing process includes the necessary correction of these delicate (and dangerous) flaws.

During the prosperous 1990's, the Rennaisance Commanders commanded prices on a par with new planes, and were extremely popular. As times get tough, and fuel prices skyrocket, however, it remains to be seen if the elegant, but not-so-efficient, "Twin Commanders" will keep their popularity.

Nevertheless, the Twin Commanders remain among the most coveted planes of all, especially in the hearts and minds and dreams of pilots everywhere.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

RH