Return to

Return toAviation Answer-Man

Gateway

Return to

Return to

Aviation Answer-Man

Gateway

Return to

Return to

First Flyers —

Who, really, were the "First to Fly"?

|

|

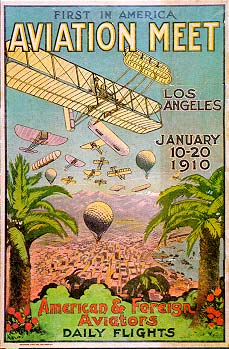

| Poster for America's first great airshow -- the 1910 Los Angeles Air Meet at Dominguez Field. While a Wright Flyer dominates the foreground, in proper patriotic fashion, the background is cluttered with the mostly French and British designs that had already eclipsed it -- reflecting the reality of the show, and the times. |

This month [December, 2003], the world pauses to reflect on the creation of the airplane, which is generally accepted to have happened a hundred years ago, this month. On December 17, 1903, Orville Wright — with brother Wilbur running alongside — made what is generally regarded as the first successful, fully-controlled free flight of a man-carrying airplane. From this moment, Humanity's reach — across boundaries, obstacles and oceans — has suddenly exploded, in less than a century, to a phenomenal capability hardly imaginable in all the previous millienia of human existence.

But it didn't all happen in one crucial moment at Kitty Hawk. The story is much more complex, and has far more heroes, than most Americans know. We take a break from our usual general-aviation history series to tell the story of the founders of general aviation: those first experimental aviators.

OK, here's a quick quiz for you:

The Wright Brothers were the...

1. First to fly.

2. First humans to fly.

3. First to fly a controlled aircraft.

4. First to fly a controlled, powered aircraft.

5. First to fly an airplane.

6. First humans to fly an airplane.

7. The single greatest obstacle to American aviation in the early 1900's.

The answer, surprisingly enough, is 7.

The Wright Brothers have become an American legend, wrapped in patriotic ego, declaring America "First in Flight." America isn't, never was. The Wright Brothers are commonly painted as independent geniuses and aviation's best friends. They were neither.

To be sure, the Wright Brothers made a handful of important contributions to flight. They provided the "final ingredients" needed to build a viable aircraft with the already-established technology.

But the Wrights also exacted a price from aviation, and particularly from American aviation — handicapping further progress in American aviation for the first few years of powered flight.

While others gave openly of their discoveries, the Wrights clung tightly to their "invention" through bloody patent-lawsuit battles that crippled U.S. aviation developments until World War I.

As a consequence of their actions, and inactions, America stumbled into World War I with an aviation industry and technology far behind both our European Allies (mainly British & French), and our enemies, the Germans.

In fact, no American-designed aircraft played a signficant role in the First World War. American combat pilots (with rare exception) flew French and British airplanes, instead.

Even long after the war, American planes were inferior to foreign designs. Though the American Curtiss Jenny trainer

Even long after the war, American planes were inferior to foreign designs. Though the American Curtiss Jenny trainer

(available cheaply by the thousands as war surplus) got the fame for various U.S. aviation firsts, it was a rickety, deadly flying nightmare -- and most of the actual productive work of early American aviation was done in license-built copies or variations of the war-surplus, British-designed, deHavilland DH-4 bomber (right).

(available cheaply by the thousands as war surplus) got the fame for various U.S. aviation firsts, it was a rickety, deadly flying nightmare -- and most of the actual productive work of early American aviation was done in license-built copies or variations of the war-surplus, British-designed, deHavilland DH-4 bomber (right).

But these facts are seldom taught or spoken of in America. It would be "unpatriotic." Well, now that the whole country has glorified the Wright stuff, it's time for the rest of the story.

|

Flight Fantasy & Early Idea Men

Since the dawn of history, man has sought to conquer that one realm perpetually out of reach of any but the gods: the skies. Myth, legend and history recount the efforts of mere mortals to soar with the gods:

attempted to flee his island prison with home-made wings. He brought along his similarly equipped son Icarus, who became too enamored of the joy of flight, flew too close to the sun, melting the wax that held the feathers in place, and plunged into what became the Icarian Sea.

attempted to flee his island prison with home-made wings. He brought along his similarly equipped son Icarus, who became too enamored of the joy of flight, flew too close to the sun, melting the wax that held the feathers in place, and plunged into what became the Icarian Sea.

More-reliable history names fools, scholars and leaders who attempted man-powered flight from towers with homemade wings — from British King Bladud (he died), to a 72-year old French general (he survived a river plunge). Italian-born scientist John Damian "flew" for Scotland's king, with only a broken leg.

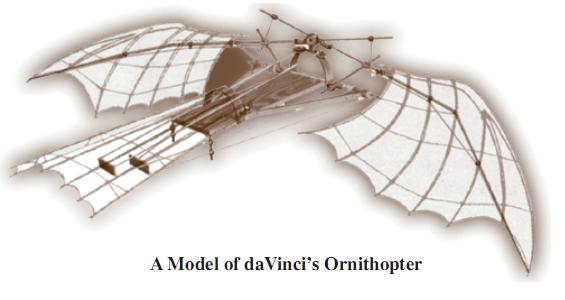

Medieval scholar Roger Bacon predicted flight, and Leonardo daVinci produced over 5,000 documents studying the idea.

Medieval scholar Roger Bacon predicted flight, and Leonardo daVinci produced over 5,000 documents studying the idea.

Apparently Leonardo finally realized that man (no matter how fit) simply doesn't have nearly the mass-to-muscle ratio of a bird, and let go of the idea, turning to ideas that would

presage the parachute and helicopter.

presage the parachute and helicopter.

But upon da Vinci's death in 1519, his research was lost, not unearthed till hundreds of years later.

The Chinese, at least 2,500 years ago, discovered wind-powered flight with the kite (eventually, the Europeans did, too). Some archaeological accounts indicate that the Chinese actually had the world's first aviators, those millenia ago: Soldiers (probably NOT volunteers) strapped to giant kites, put aloft to provide aerial reconnaisance during battles.

The Chinese also "invented" a model helicopter: a twin-rotor toy made from bird feathers and sticks, with a taut bowstring serving as the "rubber band" to power it. Popularly known in the Western world as a "Chinese top," the toy would someday fascinate the young Wright brothers, and others of their generation, and serve as an inspiration for many early aviation inventors.

First Flights

The first three aviators in the Western World were:

1. American

2. British

3. eaten

The correct answer is 3.

Not even counting possible Chinese kites,

the first known manned flight was NOT on December 17, 1903.

Try over a hundred years earlier -- on another continent.

The French brothers, Joseph Michael and Jacques Etienne Montgolfier, had developed a giant canvass bag, with a reinforced collar, that could be hoisted over a fire. Rising smoke from the fire inflated the bag, and lifted it.

September 19, 1783, they built a bigger bag, and loaded it with three passengers. Its first flight took place in the court of Versailles, outside of Paris. Before a royal crowd, including King Louis XVI of France and his wife Marie Antoinette, the first three aviators ascended into the sky beneath a giant bag of hot air, drifting for miles over Paris, before settling to earth.

The first flight was a soaring success. But the first successful aircraft's three passengers -- a sheep, a rooster and a duck -- met their demise as dinner.

However, the following November 21st, 1783, in a sturdier "Montgolfier" hot-air balloon, Francois deRozier and Marquis d'Arlandes lofted across Paris, and were not eaten.

However, the following November 21st, 1783, in a sturdier "Montgolfier" hot-air balloon, Francois deRozier and Marquis d'Arlandes lofted across Paris, and were not eaten.

The French were not only first with hot air, but first to fly a gas bag: That December 1st, inventor J.A.C. Charles rode the first hydrogen balloon across Paris.

The French were clearly first to fly successfully, in the Western world, over a century before the Wrights.

Napoleon Bonaparte was the first recorded general to employ balloons for aerial observation, but didn't much care for them.

Still the idea of an aerial spy-station was useful for some, and played a minor role in some wars of the 1800's. In the U.S. Civil War, the Union and Confederate armies both used balloons to spy on each other.

Alas, a series of mishaps — including wind blasts, the loss of a ship transporting a tethered balloon, and friendly fire — left the Confederate ballooning efforts a loss. And on the Union side, when President Lincoln replaced plodding General McClellan with fast-moving Ulysses S. Grant, the cumbersome Union balloon corps was disbanded.

But balloons remained a genuine form of human flight, and were used in many experimental ways, for over a hundred years before the Wrights, setting the stage for the beginnings of controlled, powered flight.

Airships (Dirigibles & otherwise)

Dr. Solomon Andrews & Aereon, I & II

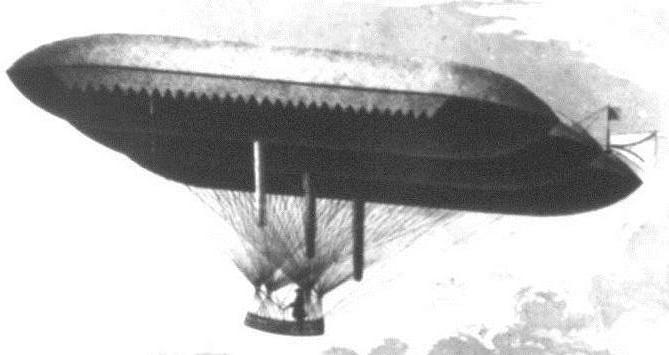

During the U.S. Civil War, in the 1860s, Dr. Solomon Andrews developed an early blimp (fshown, above left), made up of three tubular gas bags, joined side-by-side, like a gigantic pool raft. By tilting the airship up or down, and regulating its buouancy (by dumping ballast or gas), he could manage to move the ship against the wind, and actually "navigated" short distances -- perhaps the first aircraft to navigate against the wind.

His costly Aereon got little support from Congress, and his later Aereon II — after failing to return its four passengers to their origin, in an 1865 performance over Long Island — was the last of his aircraft. Future aeronauts would seek more motive power than offered by Nature alone.

Giffard & Marriott:

Giffard & Marriott:

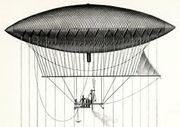

The first mechanically powered aircraft, Frenchman Henri Giffard's football-shaped "dirigible" balloon (right), managed in September 24, 1852, a 17-mile flight, at 5 miles per hour, driven by a three-horsepower steam engine.

Though it was hardly a blistering pace, and not enough to truly overcome the force of most wind, it was a way forward that showed promise. Others would seize upon the idea, leading to the first true aerial traveling vehicles.

Frederick Marriott

Frederick Marriott

In 1869, British immigrant publisher Frederick Marriott raced to be first in America to develop a fast, secure means of transcontinental travel, able to easily surmout the obstacles to westward travel: rugged terrain, bandits and hostile natives.

In May 1869, the driving of the Golden Spike -- joining east and west railroads -- ended the race, to his detriment.

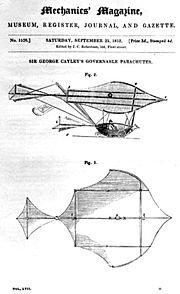

Just a month later, though, July 2, 1869, his unmanned "aerial steam car, Avitor Hermes, Jr., actually flew. The 37-foot-long, football-shaped, hydrogen-filled, muslin balloon -- with internally-mounted steam engine, turning propellors mounted on stubby wings -- was guided by a moveable tail resembling the end of an arrow. Control surfaces were copied from the model aircraft designs of Sir George Cayley (see below).

Just a month later, though, July 2, 1869, his unmanned "aerial steam car, Avitor Hermes, Jr., actually flew. The 37-foot-long, football-shaped, hydrogen-filled, muslin balloon -- with internally-mounted steam engine, turning propellors mounted on stubby wings -- was guided by a moveable tail resembling the end of an arrow. Control surfaces were copied from the model aircraft designs of Sir George Cayley (see below).

The Avitor never became a long-distance passenger transport; but it did become America's first self-propelled, controlled-flight aircraft — a title commonly misattributed to the Wright Flyer.

Moved to a pavillion at the Mechanics Fair in San Francisco, Avitor flew daily for thousands of ticket-buying spectators, for about a week, before crashing into a gas light in the hall. The hydrogen bag exploded in flame, setting fire to the pavillion, and all was lost. The disaster, lack of passenger space, and the success of the railroad, doomed further development.

In 1875, at age 70, Marriott tried to patent an idea for a triplane, carrying four passengers. The U. S. Patent Office dismissed his idea as impossible and preposterous. Over a generation later, triplanes would be among the top fighter aircraft in the First World War.

For more on Marriott and his aircraft, from the Hiller Aviation Museum, CLICK HERE

Renard & Krebs: French Flyers:

Renard & Krebs: French Flyers:

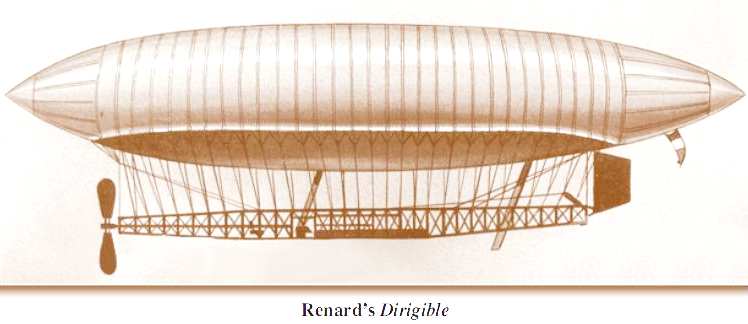

Giffard & Marriott's ideas, 15 years later, were revived by Frenchmen Renard (Reynard) and Krebs, who built their similar, but higher-performance, LaFrance (left).

Zeppelin: German Genius

Zeppelin: German Genius

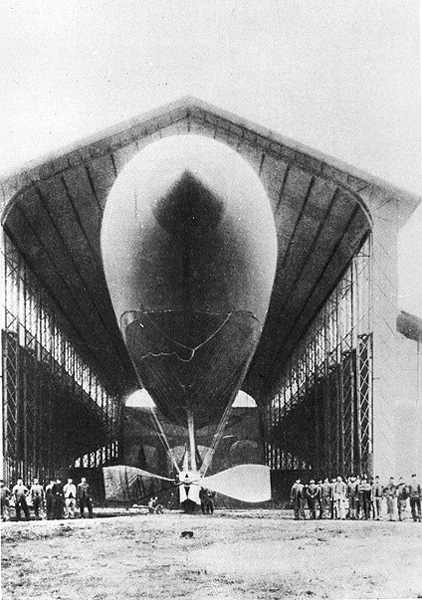

Just 25 years later, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin began using Marriott's ideas for shaping and bracing the gas bag, and for mounting a carriage under its frame, to produce the most famous lighter-than-air airships of all time — including the LZ 10 of 1909-1914 (right; the world's first successful airliner, carrying passengers safely and routinely while airplane inventors struggled to fly at all). Later, his name became a household word with his massive, globe-circling Graf Zeppelin, of the 1920s and 1930s, and the infamously tragic Hindenburg of 1936.

Santos-Dumont:

In the late 1800's, wealthy Brazilian-born, French-educated aristocrat Alberto Santos-Dumont poured his wealth into aviation, developing the most successful line of dirigibles to date.

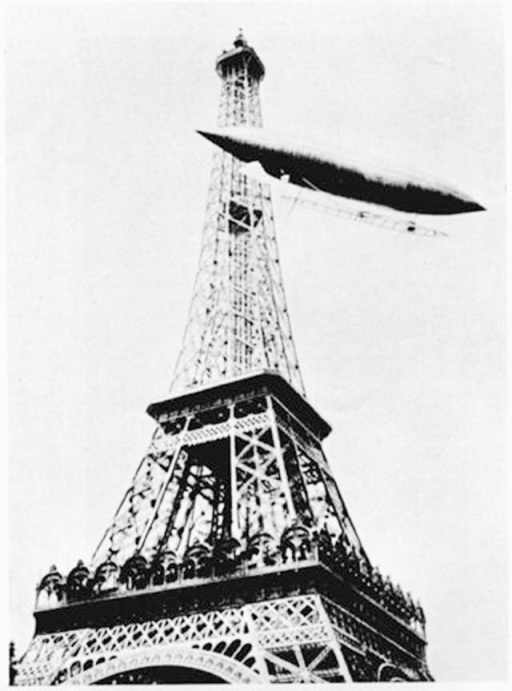

In 1901, aboard his No.6 dirigible, he captured a leading prize for being first to fly to, and around, Paris' Eiffel Tower, and return to a distant origin. He started the first regular commuter flights with his No.9 dirigible.

His dirigibles were widely viewed as the first aircraft to successfully and consistently make round trips to-and-from chosen destinations, under power and control. His reliable, gasoline-powered dirigibles, and his own piloting expertise, brought fresh credibility to human flight, and made Santos-Dumont a world hero.

The next several years would see Santos-Dumot's popularity soar, as he flew about, publicly, in one dirigible after another. The coming of the airplane, with the Wright's success in 1903, would eclipse the dirigible quickly, but the alert Brazilian would be quick to rise to the challenge.

Following Chanute's 1905 publication of the Wright Brothers' success, in 1906 Santos-Dumont designed the first French airplane, his lightweight box-kite plane 14-bis, built for him by the Voisin brothers. The 14-bis pioneered wheeled landing gear, and in 1906, became the first airplane to fly in public (leading many to believe that Santos-Dumont had achieved the first successful airplane flight). It flew brief hops, under moderate control, and was promptly hailed throughout Europe as the first successful airplane (the Wright's secretive achievements, not yet validated by any independent, internationally recognized authority, were not yet widely believed outside the United States, until the Wrights' dramatic 1908 European tour). Even after the Wrights performed in Europe in 1908, giving credence to their "first airplane" claim, Santos-Dumont's 14-bis was widely regarded as the first European plane to fly under human control.

Following Chanute's 1905 publication of the Wright Brothers' success, in 1906 Santos-Dumont designed the first French airplane, his lightweight box-kite plane 14-bis, built for him by the Voisin brothers. The 14-bis pioneered wheeled landing gear, and in 1906, became the first airplane to fly in public (leading many to believe that Santos-Dumont had achieved the first successful airplane flight). It flew brief hops, under moderate control, and was promptly hailed throughout Europe as the first successful airplane (the Wright's secretive achievements, not yet validated by any independent, internationally recognized authority, were not yet widely believed outside the United States, until the Wrights' dramatic 1908 European tour). Even after the Wrights performed in Europe in 1908, giving credence to their "first airplane" claim, Santos-Dumont's 14-bis was widely regarded as the first European plane to fly under human control.

Santos-Dumont later, in 1907, produced the first popular monoplane, the delicate little Demoiselle -- a small winged craft, pulled along by a tiny engine and large propeller, cradling the pilot underneath, scarcely a foot above the ground. The Demoiselle — though looking dangerously delicate — proved remarkably safe, and with it (and its many copies), Santos-Dumont and various other aviators set many records. The Demoiselle is often regarded as "the first light plane."

Santos-Dumont later, in 1907, produced the first popular monoplane, the delicate little Demoiselle -- a small winged craft, pulled along by a tiny engine and large propeller, cradling the pilot underneath, scarcely a foot above the ground. The Demoiselle — though looking dangerously delicate — proved remarkably safe, and with it (and its many copies), Santos-Dumont and various other aviators set many records. The Demoiselle is often regarded as "the first light plane."

.

Airplane Beginnings

Cayley: British Brain

Britain's Sir George Cayley earned

historical glory for crafting

early flying model airplanes,

using taut-bowstring propulsion. He copied the Chinese helicopter toy, and -- much more importantly -- crafted some of the earliest known model airplanes with cambered (curved surface) wings, the essential aerodynamic secret of birds — and of all airplanes today.

using taut-bowstring propulsion. He copied the Chinese helicopter toy, and -- much more importantly -- crafted some of the earliest known model airplanes with cambered (curved surface) wings, the essential aerodynamic secret of birds — and of all airplanes today.

By 1809, Cayley solved most of the mysteries of powered flight, including various aspects of lift, weight, thrust and drag, and established key mathematical formulas for flight. He specified:

and

Finally, Cayley supervised construction of the first man-carrying glider (left). In 1849, it carried his servant's 10-year-old son, the first known aerodynamic aviator.

Finally, Cayley supervised construction of the first man-carrying glider (left). In 1849, it carried his servant's 10-year-old son, the first known aerodynamic aviator.

A later, larger model flew 900 feet before crashing. His carriage-driver tired of the unnerving business of being required to fly it, and when Cayley planned a steam-engined flying beast, his driver quit.

But, had there been gasoline engines with enough power-to-weight ratio available, and a willing servant, Cayley might well have fathered the first airplane, in Britain. His published research, though, showed the way for future airplane designs.

For more on Cayley and his ideas, from Monash University, Australia, CLICK HERE

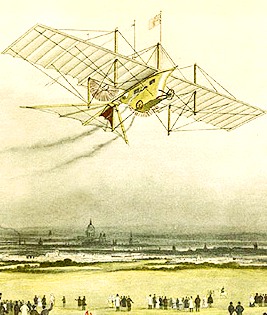

Stringfellow & Henson: British Visionaries:

Aeronautical inventors John Stringfellow and W.H. Henson -- British craftsmen -- earned a place in history with Henson's promotion of the idea of the monoplane (as imaginatively depicted in their promotional illustration at left), and Stringfellow's "invention" of the "first engine-driven model airplane to fly," (glide briefly, actually)

Aeronautical inventors John Stringfellow and W.H. Henson -- British craftsmen -- earned a place in history with Henson's promotion of the idea of the monoplane (as imaginatively depicted in their promotional illustration at left), and Stringfellow's "invention" of the "first engine-driven model airplane to fly," (glide briefly, actually)

The duo designed big powered airplanes (1842-1868) that never flew, perhaps because of the weight of their steam engines.

But their "Aerial Navigation Co." offered the first plausible design concepts of the airplane, and their company included the aforementioned Frederick Marriott, who did eventually succeed in pioneering controlled flight in America (with his Avitor Hermes, Jr. dirigible, noted above).

Ader's Eole & Avion III: French Firsts?:

French engineer Clement Ader is argued by some to have been first to fly a heavier-than-air craft: in 1890, his large steam-engined, bat-winged Eole reportedly cleared its track for a few feet, before settling back to earth. Later, his beastly Avion III, thrust down a track by two bulky 20-horsepower steam engines, may have flown briefly, too, but not successfully, and was defunded by the French military.

French engineer Clement Ader is argued by some to have been first to fly a heavier-than-air craft: in 1890, his large steam-engined, bat-winged Eole reportedly cleared its track for a few feet, before settling back to earth. Later, his beastly Avion III, thrust down a track by two bulky 20-horsepower steam engines, may have flown briefly, too, but not successfully, and was defunded by the French military.

Lilienthal - The Birdman of Berlin:

Lilienthal - The Birdman of Berlin:

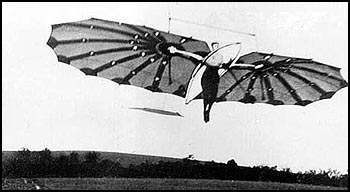

German engineer Otto Lilienthal took progress another leap forward, literally. Leaping off of tall hills, dangling from bat-like hang-gliders Lillenthal quickly became the most experienced aerodynamic flier in the world.

Starting in the dark (to avoid ridicule) at the age of 14,

with his younger brother Gustav, Otto experimented with bird-like wings. He spent his life captivated by the thought that if the ungainly stork could fly, then why not man?

with his younger brother Gustav, Otto experimented with bird-like wings. He spent his life captivated by the thought that if the ungainly stork could fly, then why not man?

Lilienthal took up engineering, and even developed an engine, anticipating its need for flight. He performed the most detailed aerodynamic studies of birds ever done. Believing that wing-flapping would be necessary, he studied the idea until proving it wrong.

The Birdman of Berlin's real gift to aviation, though, were his 2,000+ flights. Never had any human taken to wing so much, and survived. His flying discoveries aloft proved invaluable. His 18 different gliders included the first "production" gliders, sold for money.

The Birdman of Berlin's real gift to aviation, though, were his 2,000+ flights. Never had any human taken to wing so much, and survived. His flying discoveries aloft proved invaluable. His 18 different gliders included the first "production" gliders, sold for money.

With a batlike glider of 150 square feet, he was the first to soar — gliding to a higher altitude than at his departure point — on updrafts. He became world-famous as the "Bat Flyer" with flights up to a quarter-mile, including slight turns. He experimented endlessly in flight control.

The German's pioneering flights ended in 1896, with a fatal wing stall (typically, a loss of adequate flying speed) from 50-100 feet. Though he was the last of the "wing-flappers," he proved the need for fixed wings. Generously sharing his discoveries, he provided ingenious and life-saving guidance to future aviators.

Hargrave - Aussie Aviator.

British-born Australian astronomer Lawrence Hargrave, fascinated by flight, retired from astronomy to tinker in aviation.

|

| Lawrence Hargrave, immortalized on Australia's $20 bill. |

In 1894, Hargave earned the praise of the leader of America's prestigious National Geographic Society (telephone-inventor Alexander Graham Bell), for a 34-pound "kite-plane" motorized model, which lifted a 208-pound load.

Hargave declined a patent, though, feeling his reward would come through market support of superior craftsmanship, once the secret of flight was mastered. His sturdy, stable, full-size plane design, though, suffered a basic limitation: no suitable engine.

Still, Hargrave kept experimenting, reporting his findings to Octave Chanute, who spread them around the world -- influencing the Wrights and others.

A month after the Wrights flew, Hargrave was informed of that event by Octave Chanute (see below), accelerating his drive for success. But countless creative efforts at finding or inventing adequate power failed, and fellow Australians offered him little more than ridicule.

A box-kite plane echoing his ideas, flown by Santos-Dumont, in 1906, became the first plane to fly in public (see photo by "Santos-Dumont" topic, above), and in 1910, a French Voison box-kite biplane (flown by magician Harry Houdini) became the first plane flown in Australia. Yet Australia never recognized Hargrave as the aeronautical leader in their midst, till after his death.

Pilcher - Scottish Sailor in the Sky

Scottish naval engineer Percy Pilcher began his aviation experiments copying the batlike gliders of Lillenthal -- consulting directly with the Birdman of Berlin. Pilcher also experimented with the ideas of Australia's Hargrave.

Pilcher's sailing expertise translated into exceptionally well-built gliders. Tow-launched by a team of horses, his gliders set distance records, up to 300 yards in 1897.

For his best glider, Pilcher planned to mount a small engine, and attempt powered flight. To raise money, he gathered potential investors together on September 30th, 1899, for a demonstration flight. However the weather turned nasty, soaking the fabric-skinned glider, and buffeting it with turbulence.

Pilcher was determined to go through with the important demonstration, though. Following a difficult launch he soared 60 feet high before a gust of wind snapped the tail, sending him plummeting to earth, killing him.

Several months later, though, his research was sought out by Wilbur Wright.

Chanute: Godfather of Aviation:

French-born Octave Chanute immigrated to the U.S. at age 7. A brilliant construction engineer with the railroads, he pioneered cresote preservation of railroad ties, designed New York's elevated train system and crafted some of the first bridges to span the huge Mississppi River.

Retiring to Chicago in 1889, Chanute turned to the puzzle of flight, developing the most sophisticated system of research to date. He published vast amounts of valuable research, gathered from around the globe, and provided it openly to the aviation community. His landmark book, Progress in Flying Machines, was early aviation's definitive historical and technical reference of the time.

Tinkering with gliders, Chanute eventually settled on a biplane design, which established the biplane "bridge-truss" framework that would dominate aircraft designs for the next quarter-century. He also saw the need for inherently stable aircraft, and moveable control surfaces.

In 1896, age 64, Chanute began directing his assistants through the business of flying Chanute's biplane glider from sandhills along Lake Michigan, with over 1,000 flights, many over 100 feet long, making Chanute the world's leading flight expert -- developing the best gliders in the world.

Chanute quit experimenting, and took up helping others in search of flight -- serving as the global clearinghouse for gathering and disseminating information on the latest developments in flight -- becoming the "Godfather of Aviation."

Many would-be aviators corresponded with him, seeking out his knowledge. Among them was a young man who wrote him in 1900, from Dayton, Ohio, confessing to be "afflicted with the belief that flight is possible to man," signing it "Wilbur Wright." Chanute took an interest in the intelligent young man, and began a 400-letter correspondence, encouraging and guiding the Wright brothers in their experiments, and visiting with them.

Montgomery - California's Birdman:

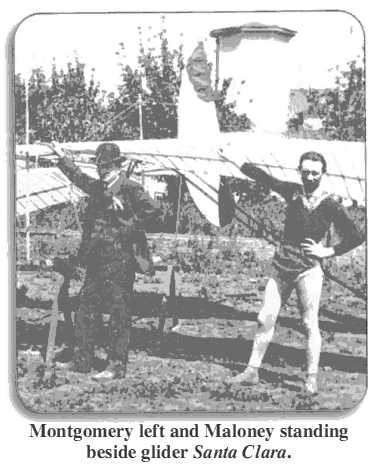

Studying birds obsessively since childhood, California science professor J.J. Montgomery, experimented with gliders of his own devising. In 1883, with his brother, he apparently secretly flew a glider over 600 feet, downhill, from a San Diego seaside cliff, though no other witnesses were present.

Montgomery avoided others' research, focusing on his own ideas of how to achieve flight. His 1904 experiments with man-carrying, tandem-wing gliders culminated in pilot Daniel Maloney's 4,000-foot ascension in Montgomery's balloon-borne glider; Maloney then cut the glider loose from the balloon, and glided safely to earth. Octave Chanute was amazed. Telephone inventor Alexander Graham Bell, a participant in early U.S. aeronautical research, praised his work as pioneering.

Whitehead - Connecticut's "First":

According to FAA Aviation News (April 1978), German immigrant Gustave Whitehead (born "Gustav Weisskopf"), obsessed with flight from early childhood, found his way to Boston in 1892 -- arriving penniless, jobless, with only seafaring job skills.

Before Lilienthal's death, though, Whitehead had apparently corresponded with the Berlin Birdman, and learned about gliders. Impressing the Boston Aeronautical Society with his aeromechanical knowledge, and Lillenthal connection, Gustave Whitehead got their backing to build a flying machine.

Whitehead's "Boston Flyer" imitated Lilienthal's last biplane gliders, but failed to fly with its moveable wings and hand-driven prop. His patrons faded away, and he drifted to Johnstown and Pittsburgh, Penn., mining coal, while developing a steam engine for his first flying machine.

|

Gustave Whitehead UPDATE,

The Gustave Whitehead controversy took a major turn, in the Spring of 2013, when "IHR Jane's" — the famed British publisher of the oldest, most authoritative, most respected annual reference work in aviation: Jane's All the World's Aircraft — announced it would henceforth revise its records to indicate that Whitehead's 1901 alleged flight truly happened — making Whitehead, in their estimation, the first to fly an airplane in fully controlled flight.

This has led to a flurry of publicity and public debate.

For key examples of the news & perspectives, from various sides of the issue, see:

...or see:

|

In 1899, Whitehead's flying beast (carrying him and engine-stoker Louis Davarich) rose to 25 feet (according to Davarich), before crashing into a building -- hospitalizing Davarich, and getting Whitehead booted out of town.

Drifting to Bridgeport, Conn., Whitehead later claimed to have built and tested (sometimes flown) 18 more aircraft in two years, including a 2-seat glider.

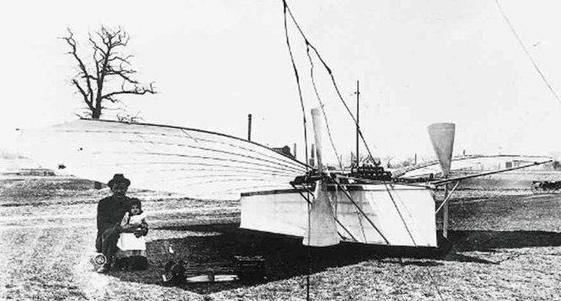

Gustave Whitehead's real claim to fame, perhaps, was design #21 (shown above), which self-declared helper Junius Harworth described as...

"...a monoplane having four cylinder, two-cycle motor located forward... using two propellers... constructed of pine, spruce, and bamboo, reinforced with... steel tubing and piano wires... wing coverings... of Japanese silk, varnished and fastened to... bamboo struts with white tape," all weighing "about 800 pounds."

August 18-19, 1901, the Bridgeport Sunday Herald reported that Whitehead, in the presence of four witnesses (including reporter Richard Howell) had flown design #21 a half-mile, rising to about 50 feet. (see transcript under the title "Flying", at: http://www.wright-brothers.org/ History_Wing/ History_of_the_Airplane/ Who_Was_First/ Gustav_Whitehead/ Whitehead_Articles.htm #herald).

Though repeated in the next day's New York Herald, it was probably regarded as a investor-tempting hoax or exaggeration -- common in this era of frantic, competitive first-flight attempts. No instrument recordings or photos existed to prove the event, and it was forgotten. A recent replica, however, using modern engines, has flown successfully.

According to Gustave's subsequent (sometimes contradictory) writings, he followed up with a flying boat, which mechanic Anton Pruckner reportedly witnessed soaring over Long Island Sound, and landing there. But iconoclastic Whitehead had few witnesses to vouch for him, and no photos or instrument verification of his flights.

Whitehead starved his family to feed his frenzy for flight, and left them penniless when he died in 1927 -- ironically the year that a firestorm of global aviation enthusiasm erupted, following the trans-Atlantic solo of Charles Lindbergh.

Maryland writer Stella Randolph took an interest in Whitehead, and dug up his records, publishing The Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead (1937) and Before the Wrights Flew (1964). American aeronautical history organizations dismissed her work, but in 1966 Connecticut historians named Gustave "Father of Connecticut Aviation."

Whether he was first or not is unknown, for lack of photos, though some photos show him flying an early glider. But his impact on aviation was clearly limited, if any.*

* [UPDATE NOTE: Subsequent indications that the Wrights & their chief rival, Glenn Curtiss, may have taken an interest in Whitehead's work, raise new questions, now, about Whitehead's possible influence on early aviation. ~RH, April, 2013]

IMPORTANT UPDATE on Whitehead's possible "First" status, April 2013:

See 'UPDATE' box, above right.

"Mad Dick" from Down Under:

From New Zealand's South Island comes the tale of Richard Pearse, another crabby aero-nut, known as "Mad Dick" by his unimpressed fellow farmers.

From New Zealand's South Island comes the tale of Richard Pearse, another crabby aero-nut, known as "Mad Dick" by his unimpressed fellow farmers.

According to Plane & Pilot magazine (April 2002), at the turn of the century, Pearse pored over aeronautical articles in science jounals in the local library, and turned his farming skills into building flying machines that actually flew, spooking local livestock on the Canterbury Plains, as he dashed along Waitohi Road.

His aircraft was witnessed by various annoyed or amused locals, sometimes leaping 100-150 yards (well beyond the Wright Brothers' 40-yard "first" flight).

Through interviews and intriguing detective work, subsequent historians think they've established at least five flights, between March 31, 1902 and July 10, 1903, all before the Wright's first powered flight.

Through interviews and intriguing detective work, subsequent historians think they've established at least five flights, between March 31, 1902 and July 10, 1903, all before the Wright's first powered flight.

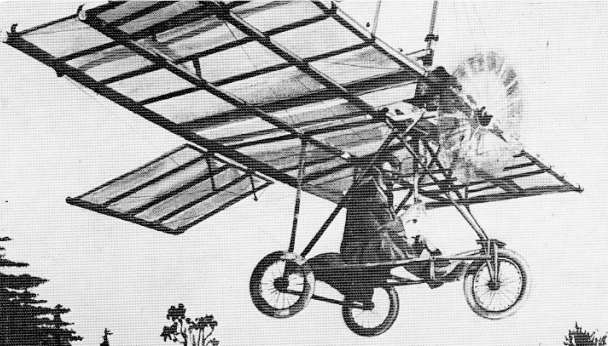

Sketches, based on eyewitness accounts, reveal a tricycle frame dangling beneath a squarish, parasol wing, with a slot in the middle for the propellor of its single, homemade engine. Small flaps (perhaps early ailerons, for roll control) protrude from openings in the outer wings.

Pearse's later flights seem well-established, making him the father of New Zealand aviation, but his pre-Wright ventures had no impact on aviation.

Alas, at the turn of the century, surrounded only by contemptuous farmers, on the southernmost inhabitated place on earth, with no photograph of his flights, he remained nearly unknown, and was largely forgotten -- save for a simple monument on Waitohi Road, topped by a model of his first flying machine, and Gorden Ogilvie's book, The Riddle of Richard Pearse.

(For more from a New Zealand museum, CLICK HERE., and from a New Zealand educational website... CLICK HERE.)

Langley & Manly:

The Grand Academic Failure:

As Secretary of the Smithsonian Institute, aristocratic professor Samuel Pierpoint Langley had the scholarly credentials to solve the riddle of powered flight. He was the world's leading pioneer in astrophysics, and a leading figure in America's scientific establishment.

Langley succeeded in building a huge tandem-winged, steam-powered model aeroplane -- which managed half-mile flights, witnessed by Alexander Graham Bell. In ill health, age 64, Langley retired back to astronomy, only to be nudged back into aviation in 1898 by President McKinley, who thought an airplane might have value in the Spanish-American War.

Langley succeeded in building a huge tandem-winged, steam-powered model aeroplane -- which managed half-mile flights, witnessed by Alexander Graham Bell. In ill health, age 64, Langley retired back to astronomy, only to be nudged back into aviation in 1898 by President McKinley, who thought an airplane might have value in the Spanish-American War.

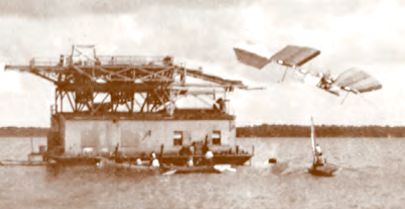

By 1902, with vast government and Smithsonian funding, Langley had built a massive tandem-winged "Aerodrome A" -- powered by a superb 125-pound, 52-horsepower radial gasoline engine designed by his aide, Charles Manly, who attempted to fly the plane.

Upon its first public launch -- Oct 7, 1903, from a catapult atop a giant houseboat in the Potomac -- the flimsy plane's massive forward wing buckled, and the craft glided swiftly from the boat into the water. Mortified, Langely protested that the accident was due to the plane's tail snagging in the catapult.

Upon its first public launch -- Oct 7, 1903, from a catapult atop a giant houseboat in the Potomac -- the flimsy plane's massive forward wing buckled, and the craft glided swiftly from the boat into the water. Mortified, Langely protested that the accident was due to the plane's tail snagging in the catapult.

Manly survived, and the Aerodrome was rebuilt. Dec. 8th, with a crowd watching, and a lot of government money riding on the project, Langley reluctantly launched the plane into an 18-mph headwind. This time, the aft wing collapsed, and the plane dove straight into the river, nearly drowning Manly.

Government funding halted. A flood of public ridicule drove the shy, sensitive academic out of sight -- dying, of a broken heart it is said, three years later. Ironically, nine days after his last attempt, Orville Wright flew the first photographically-recorded successful flight of a controlled, powered, heavier-than-air, man-carrying airplane.

Loyal colleagues at the Smithsonian, though, contended that Langley's plane was viable, and in 1914, hired the Wrights' chief rival, Glenn Curtiss, to test-fly the Aerodrome. Embroiled in a patent lawsuit with the Wrights', Curtiss saw this as a chance to discredit the Wrights' claim to having essentially invented powered, controlled aerodynamic flight. Curtiss quietly modified the Langley craft extensively, added pontoons to enable it to fly from water as a seaplane, and "successfully" flew it 150 feet (though possibly never rising clear of ground-effect lift).

Thereafter, though no one (neither courts nor the public) were fooled, the Smithsonian — the United States' national museum — displayed the Aerodrome A as "the first man-carrying aeroplane in the history of the world capable of sustained free flight."

The insulted Wrights withheld their original Flyer from the museum, eventually sending it to a British royal museum — until the Smithsonian retracted their Langley claim (in a contractual agreement with the Wrights), and were allowed to bring the Wright Flyer back to the U.S., following World War II.

The Wright Stuff:

It's commonly accepted that the Wright Brothers were the decisive pioneers in aviation. But it is all-too-easily forgotten, particularly in their homeland, that they followed in the footsteps of failures, and stood on the shoulders of giants, to reach the prize of controlled, powered, aerodynamic flight.

Foreign-born Octave Chanute was their business and technical mentor. Through him they harvested the discoveries of foreigners Cayley, Lilienthal, Hargrave, Pilcher and others.

Mechanic Charlie Taylor crafted the engine that gave them the essential power-to-weight ratio that other aviator-inventors were denied. Virtually all the necessary secrets of powered flight, save for one, were handed them on a silver platter.

The remaining secret -- roll control -- was not obvious, except to those who needed to lean into turns: bicyclists and motorcyclists. And, of course, the Wright Brothers, professional bicycle builders, were bicycle experts.

(It's worth noting that the aileron -- today's preferred means of roll-control, which quickly eclipsed the Wrights' wing-warping -- was introduced to American aviation by the Wrights' chief rival, Glenn Curtiss -- a leading motorcycle racer.)

To be sure, the Wrights paid their dues, with extensive, sophisticated research, perfecting each known aspect of flight as best they could. They pioneered modern aeronautical engineering research and development, crafted an early wind-tunnel, and approached their experiments with careful, sober reasoning.

Their propeller design was profoundly refined, correctly designed as a spinning wing -- rather than an aeronautical version of a boat propeller (like those before them). Their propellers' resulting efficiency greatly improved their chance for success.

Nevertheless, the Wrights were not lone creators of flight, but merely among those, throughout the world, who had built up the knowledge base of human flight over centuries.

Had Wilbur and Orville's mechanic's engine failed (or had the gasoline engine not yet been invented), or had they lacked a camera on Dec. 17th, 1903, or simply run afoul of a fatal gust of wind, history might never have noted them -- and America might never even have been the "birthplace" of the airplane.

But the gifts of many became the triumph of two -- and the fantasies of foreigners became the "achievement of America" -- just a hundred years ago, this month.

~ R.Harris, December, 2003

minor revisions 2007 & 2013.

Major official & organizational websites:

A History of Aeronautics

by Prof. E. Charles Vivian (circa 1920), a classic source:

Other sites: