Return to

Return toAviation Answer-Man

Gateway

Return to

Return to

Aviation Answer-Man

Gateway

Return to

Return to

Planes on the Plains

Note to the Reader: This is a rough draft release only, for demonstration purposes. There are a few errors which remain to be identified and resolved. Comments and corrections are invited.

(click here)

~RH

_________________________________________

As the 1800's gave way to the 1900's, Wichita and its surroundings were starting to calm a bit.

Wichita quieted suddenly, but did not collapse. Optimistic, bullish city leaders kept angling for new ways to make the most of Wichita's situation. A considerable wealth had been brought to this tiny town by cattle, by their buyers, and by the free-spending, freshly-paid drovers who delivered them. And some of this wealth was turned into beef processing.

In true Wichita fashion, the city had made the most of its situation, and even of its frigid winters. The shipped beef was kept cold by chipped ice from Wichita's ice house, which gathered huge blocks of ice from ponds and rivers during the bitterly cold winters, and stored them in straw through the rest of the year in a large warehouse. The busy, productive ice house soon was even selling its ice to places back East.

While here, farmers did their shopping. As a leading terminal for beef and grain, Wichita was fast becoming a major hub of agricultural commerce.

While -- back East -- Henry Ford began building automobiles, and Orville and Wilbur Wright were struggling to make flying machines out of bicycle parts, the rural communities of America's heartland were half a century behind. They still moved about on foot or horseback, or in horse-drawn wagons. The occasional steam-engined automobile was an object of amazement (or annoyance -- a Wichita law required automobile drivers to stop their "horseless carriage" at every intersection, get out, go around front, look both ways to be sure the coast was clear, and then get back in the car to proceed.)

No longer a dusty saloon-and-general-store town, the grand and elegant Wichita became the known as the "Peerless Princess of the Prairie."

That wealth was being supplemented by a growing entrepreneurship of shrewd, inventive craftsmen, who would come to this "boom town" to sell their wares to the increasingly prosperous townfolk.

Having originally tried marketing the lamps elsewhere, Coleman found resistance from people who'd been "burned" by being sold shoddy lamps by someone before him. So Coleman responded by selling street lamp "service" -- promising to maintain the lights himself.

Wichita's City Council fussed over whether to invest in street lamps, which might further public safety and extend local business hours.

Wichita's streetlights would soon lead to Coleman's development of his bright, reliable "Coleman lantern" -- the most sought-after source of light for rural America, before the arrival of rural electric service three decades later. The huge demand -- nationwide -- for Coleman lanterns, would fire up Wichita's first great manufacturing company, the Coleman Company, which would help prepare Wichita for the sophisticated mass-production of metal products -- paving the way for its future aviation industry.

A local blade maker found a national market for his "Keen Kutter" razor blades, and was soon manufacturing them in a huge building just east of downtown. Other factories were built by a nail-and-wire manufacturer, a watch-maker, and a builder of railroad cars for livestock -- the Burton Stock Car Company -- whose factory would eventually change hands, and become the first factory in Wichita to produce airplanes.

The city's busy slaughterhouses gave rise to a soap company which -- like all soap companies of the day -- used the "tallow" renderings from the slaughterhouses to make soap. The "Yucca Soap Company" soon developed an aromatic cough-suppressing ointment that came to be known as "Mentholatum," a popular American home remedy -- in various forms -- to this day.

By the turn of the century, no fewer than 10 rail lines, from all points of the compass, converged on this now-substantial city of 45,000 (see map, below) -- particularly converging at the stockyards and grain elevators, and at the huge, new Union Station (left).

Determined to keep Wichita at the center of agriculture, commerce and industry, local and state governments continued to lavish money on building and improving routes to the city that billed itself as "Midway U.S.A."

(Later, in the 1920's, Wichita grain magnate Roy Garvey would begin buying up wheat farms, grain storage silos and grain elevators until eventually becoming the nation's leading grain-producer and controlling the world's largest network of grain-storage elevators -- putting him in a position of incredible power in world agriculture. The powerful Garvey family would become Wichita's dominant millionaires for generations.)

The city (and the county and the state) wrestled continually with how to provide "relief" for the people in desperate circumstances -- often one-fifth of the population -- who had no work, or whose crops were a complete loss, and were sometimes on the verge of starvation. But the stout self-reliance that had characterized the pioneers could be matched by stingy self-centeredness and pride in times of trouble.

Fortunately, for the starving poor in Wichita and its surroundings, various churches, businesses, individuals and civic groups "back East" were surprisingly generous with distant Kansas during hard times (in 1874 they sent Kansas's needy over 100 railroad-cars' worth of relief supplies).

Often isolated from each other by miles, the Kansas farmers' desperate struggle for survival bred a culture steeped in self-reliance, hard work, long hours, low pay, risky living, ingenuious tenacity, stingy frugality, and hard-hearted instincts of self-preservation. As farmers and their elected representatives took their values to the statehouse, these characteristics would shape the state's politics -- and Kansas would come to be known as "the most Republican state in the nation." As the farmers came to town to find city jobs in hard times, their values further shaped the culture and industry of Wichita, and its politics.

Striking Oil:

Supplemented by the frugal creativity of the region's ever-struggling wheat farmers, the Wichitans -- now masters at building and fixing horse-drawn wagons and primitive frontier machinery, sophisticated gasoline lanterns, and even railroad cars and equipment -- were proving to be quite the handymen.

By the dawning of the age of the automobile, Wichitans suddenly found a new use for their mechanical skills -- making oil-drilling equipment. Oil -- the "black gold" which fueled the new automobiles and Coleman lanterns -- was discovered in great abundance just east of town, in 1915, with the one of the biggest oil strikes in American history up to that time.

The discovery led to a land rush, of sorts, as "wildcatters" from all over the country converged on Sedgwick and Butler counties -- tough, experienced well-drillers, gambling all they had to blindly, optimistically buy up the "mineral rights" to whatever was under a particular parcel of land, then drilling a few very expensive holes, praying for a strike. Among the high-stakes gamblers was an iron-fisted, stubborn wildcatter named Jake Mollendick. His successful strike would soon change more than his life -- it would change the future of aviation. (See Chapter 3)

Over time, the oil strikes would spread into neighboring Oklahoma, whose new oil companies would turn to the experienced suppliers of Wichita for their equipment. Fred Koch was among those who made a fortune supplying the oil processors in the surrounding region.

With money literally gushing up out of the ground in the surrounding area, Wichita had again become a center of sudden wealth. Many local oil prospectors ("wildcatters") -- daring high-stakes gamblers who risked everything they had on holes in the ground -- had struck it rich here, and were feeling lucky. They were ready to roll their dice on any interesting new enterprise that presented itself. And boy did opportunities present themselves...

The

"Air Capital of the World"

isn't where you'd expect.

Chapter 2

The Turn of The Century:

The Money Rolls In

Copyright 2002 by Richard Harris

All Rights Reserved

The state government's "quarrantine area," blocking Texas Longhorns from eastern Kansas, had worked to Wichita's benefit for several years, but now the encroaching farmers with their fences -- and farm cows fatally susceptible to the roaming Longhorns' "Texas fever" -- demanded that the legislature extend the Longhorn cattle quarrantine to the lands around and beyond Wichita, forcing the cattle drives to meet the railroad over a hundred miles westward.

The state government's "quarrantine area," blocking Texas Longhorns from eastern Kansas, had worked to Wichita's benefit for several years, but now the encroaching farmers with their fences -- and farm cows fatally susceptible to the roaming Longhorns' "Texas fever" -- demanded that the legislature extend the Longhorn cattle quarrantine to the lands around and beyond Wichita, forcing the cattle drives to meet the railroad over a hundred miles westward.

If the cattle wouldn't be loaded onto trains in Wichita, then (since those trains ran through Wichita) at least the cattle could be off-loaded there -- and slaughtered, and efficiently-shipped eastward as pre-cut, pre-packed beef. Wichita's stockyards were now the end of the line for millions of cattle, and the Wichita stockyards (wisely placed on the north side of Wichita, to favor the prevailing southerly winds) again reeked of cattle and money.

If the cattle wouldn't be loaded onto trains in Wichita, then (since those trains ran through Wichita) at least the cattle could be off-loaded there -- and slaughtered, and efficiently-shipped eastward as pre-cut, pre-packed beef. Wichita's stockyards were now the end of the line for millions of cattle, and the Wichita stockyards (wisely placed on the north side of Wichita, to favor the prevailing southerly winds) again reeked of cattle and money.

At the same time, the value of Wichita was growing as a transportation hub for farmers from throughout Kansas and northern Oklahoma -- particularly wheat farmers -- who brought their grain to Wichita for sale to the stockyards (which fattened the cattle with grain before slaughter), and for sale to the big cities back East for bread.

At the same time, the value of Wichita was growing as a transportation hub for farmers from throughout Kansas and northern Oklahoma -- particularly wheat farmers -- who brought their grain to Wichita for sale to the stockyards (which fattened the cattle with grain before slaughter), and for sale to the big cities back East for bread.

After being harvested, wheat was gathered into grain elevators (like the one at right, preserved in Wichita's historic "Cow Town"), and then held for rail shipment at the most opportune moment -- earning a tidy "storage fee" for the elevator operators.

After being harvested, wheat was gathered into grain elevators (like the one at right, preserved in Wichita's historic "Cow Town"), and then held for rail shipment at the most opportune moment -- earning a tidy "storage fee" for the elevator operators.

By 1890 the city had grown -- in just 20 years -- from a handful of pioneers to a bustling town of over 40,000 people. With city leaders eager to make the most of their earnings, much of the money was lavished on public works. The city built roads, bridges, even railroads to put Wichita at the crossroads of commerce. At the same time, Wichita invested heavily in grand public buildings which would last for generations: a giant, stone-block county courthouse, two colleges, and more. Wichita's majestic, castle-like City Hall (left), and its massive Forum auditorium (right),

By 1890 the city had grown -- in just 20 years -- from a handful of pioneers to a bustling town of over 40,000 people. With city leaders eager to make the most of their earnings, much of the money was lavished on public works. The city built roads, bridges, even railroads to put Wichita at the crossroads of commerce. At the same time, Wichita invested heavily in grand public buildings which would last for generations: a giant, stone-block county courthouse, two colleges, and more. Wichita's majestic, castle-like City Hall (left), and its massive Forum auditorium (right),

became awe-inspiring testament to the value of food, and to the power of wealth wisely invested -- and testament to the city's faith in its own future.

became awe-inspiring testament to the value of food, and to the power of wealth wisely invested -- and testament to the city's faith in its own future.

Among them was a law-student-turned-craftsman, W.C. Coleman (left), who'd developed a brilliant gas-powered streetlight.

Among them was a law-student-turned-craftsman, W.C. Coleman (left), who'd developed a brilliant gas-powered streetlight.

They finally agreed to try it, and the investment paid off in ways the city could never have imagined.

They finally agreed to try it, and the investment paid off in ways the city could never have imagined.

Despite its tranportation activity, industrial development, and rising wealth -- and in part because of it -- Wichita was still a typical high-plains city, serving as a hub of agriculture.

Despite its tranportation activity, industrial development, and rising wealth -- and in part because of it -- Wichita was still a typical high-plains city, serving as a hub of agriculture.

The rich prairie soil grew grain readily, and tens of thousands of farmers moved to Kansas to reap the bounty Nature offered -- pushing back the native Americans (and the buffalo herds which sustained them) -- the immigrant settlers from the Eastern U.S., and from Central and Eastern Europe, struggled with their horse-drawn plows to turn the foot-deep topsoil into food.

The rich prairie soil grew grain readily, and tens of thousands of farmers moved to Kansas to reap the bounty Nature offered -- pushing back the native Americans (and the buffalo herds which sustained them) -- the immigrant settlers from the Eastern U.S., and from Central and Eastern Europe, struggled with their horse-drawn plows to turn the foot-deep topsoil into food.

With the introduction of Russian "Turkey Red" winter wheat, Kansas became one of the nation's chief sources of grain. And Wichita became a leading center for the storage, shipping and flour-milling of the grain from Kansas (and Oklahoma). If Kansas had become "America's Breadbasket" -- as was often noted -- then Wichita had become the breadbasket's handle.

With the introduction of Russian "Turkey Red" winter wheat, Kansas became one of the nation's chief sources of grain. And Wichita became a leading center for the storage, shipping and flour-milling of the grain from Kansas (and Oklahoma). If Kansas had become "America's Breadbasket" -- as was often noted -- then Wichita had become the breadbasket's handle.

But times were not always good. Economic turmoil nationwide had extreme ramifications for a city so dependent on supplying the markets of the nation. And the vagaries of Kansas' extreme weather played havoc with the fortunes of farmers, who had to gamble their whole wealth each year on seed for a crop that might, or might not, come through in the following harvest season. A farmer could be wiped out by a grasshopper swarm, prairie fire or hailstorm. One bad winter, or dry summer, could leave hundreds of farmers and their families completely penniless, and even thin the out-of-state cattle herds.

But times were not always good. Economic turmoil nationwide had extreme ramifications for a city so dependent on supplying the markets of the nation. And the vagaries of Kansas' extreme weather played havoc with the fortunes of farmers, who had to gamble their whole wealth each year on seed for a crop that might, or might not, come through in the following harvest season. A farmer could be wiped out by a grasshopper swarm, prairie fire or hailstorm. One bad winter, or dry summer, could leave hundreds of farmers and their families completely penniless, and even thin the out-of-state cattle herds.

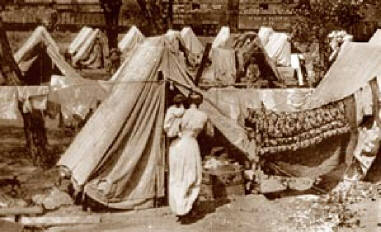

The resulting loss of business to Wichita could leave hundreds of city workers living in tents, or on the street.

The resulting loss of business to Wichita could leave hundreds of city workers living in tents, or on the street.

When, in the summer of 1874, a combination of storms, drought, scorching heat and clouds of grasshoppers destroyed virtually all the crops in central Kansas, Governor Osborn proudly declared "Kansas may be poor, but she can and will take care of her own needy." However, the most generosity he could extract from the skinflint Legislature was a bill allowing counties to vote to issue bonds to raise relief money amounting to one dollar per person in each county -- scarcely providing enough money for a day's food for every citizen -- and the recipients of this relief had to sign a pledge to pay it back with interest.

When, in the summer of 1874, a combination of storms, drought, scorching heat and clouds of grasshoppers destroyed virtually all the crops in central Kansas, Governor Osborn proudly declared "Kansas may be poor, but she can and will take care of her own needy." However, the most generosity he could extract from the skinflint Legislature was a bill allowing counties to vote to issue bonds to raise relief money amounting to one dollar per person in each county -- scarcely providing enough money for a day's food for every citizen -- and the recipients of this relief had to sign a pledge to pay it back with interest.

Tied to the land -- which they could not move to better weather -- and too poor to buy farms anywhere else, the desperate, hungry Kansans tightened their belts, and held on as best they could for another season, and maybe another chance. Death on the prairie, though, was all too common -- from starvation, dehydration, illness, childbirth, freezing, floods and storms, Indian attacks, outlaws, accidental injury, animal attacks and heat stroke. The strain of prairie hardships often drove men and women mad. In a time when the average life expectancy was less than 55 years, Kansas "sodbusters" were truly lucky to last that long.

Tied to the land -- which they could not move to better weather -- and too poor to buy farms anywhere else, the desperate, hungry Kansans tightened their belts, and held on as best they could for another season, and maybe another chance. Death on the prairie, though, was all too common -- from starvation, dehydration, illness, childbirth, freezing, floods and storms, Indian attacks, outlaws, accidental injury, animal attacks and heat stroke. The strain of prairie hardships often drove men and women mad. In a time when the average life expectancy was less than 55 years, Kansas "sodbusters" were truly lucky to last that long.

Wichita becomes "Richita"

By the end of the First World War, around 1918, Butler County's "El Dorado" oil field was producing 10% of America's oil. The boom would lead to the development of oil refineries, and pipelines -- and then to the global oil-processing empire of Wichita's Koch family (pronounced "coke")-- soon one of America's richest families.

By the end of the First World War, around 1918, Butler County's "El Dorado" oil field was producing 10% of America's oil. The boom would lead to the development of oil refineries, and pipelines -- and then to the global oil-processing empire of Wichita's Koch family (pronounced "coke")-- soon one of America's richest families.

Koch's shrewd dealings -- particularly with the new Communist government of Russia which wanted to lubricate its industrial future with oil refineries -- would soon make Koch one of the world's richest men, and father of America's largest privately-held company -- Koch Industries (still today one of America's five biggest family-owned companies -- dealing in oil and gas processing around the world) (One of Koch's many refineries is shown at right).

Koch's shrewd dealings -- particularly with the new Communist government of Russia which wanted to lubricate its industrial future with oil refineries -- would soon make Koch one of the world's richest men, and father of America's largest privately-held company -- Koch Industries (still today one of America's five biggest family-owned companies -- dealing in oil and gas processing around the world) (One of Koch's many refineries is shown at right).

for

Chapter 3:

Here Come those Magnificent Men

& Their Flying Machines

Click Here

In the next chapter, the frontier spirit brings a whole new kind of pioneering, in a whole new territory -- above the ground. Wichita's good fortune leads to wild risk-taking in the sky. Barnstormers Matty Laird and Clyde Cessna try to strike it rich in Wichita by flying stunts -- but wind up starting an industry.

In the process, Wichita becomes the home of Swallow Airplane Co. -- America's first successful commercial airplane-manufacturing company, which provides the nation's first pioneering commercial airmail planes.

In the next chapter, the frontier spirit brings a whole new kind of pioneering, in a whole new territory -- above the ground. Wichita's good fortune leads to wild risk-taking in the sky. Barnstormers Matty Laird and Clyde Cessna try to strike it rich in Wichita by flying stunts -- but wind up starting an industry.

In the process, Wichita becomes the home of Swallow Airplane Co. -- America's first successful commercial airplane-manufacturing company, which provides the nation's first pioneering commercial airmail planes.

That leads to the collaboration of Walter Beech, Clyde Cessna and Lloyd Stearman -- who team up to create the highest-volume producer of airplanes in the world -- Travel Air.

That leads to the collaboration of Walter Beech, Clyde Cessna and Lloyd Stearman -- who team up to create the highest-volume producer of airplanes in the world -- Travel Air.

Breaking world records, saying "No" to "Lucky Lindy," designing a race plane that suddenly changes the shape of military aviation, and bringing light to all the world -- all in the next exciting chapter...

Breaking world records, saying "No" to "Lucky Lindy," designing a race plane that suddenly changes the shape of military aviation, and bringing light to all the world -- all in the next exciting chapter...

Return to

Return to

Planes on the Planes

Introduction

Return to

Return to

Aviation Answer-Man

Gateway